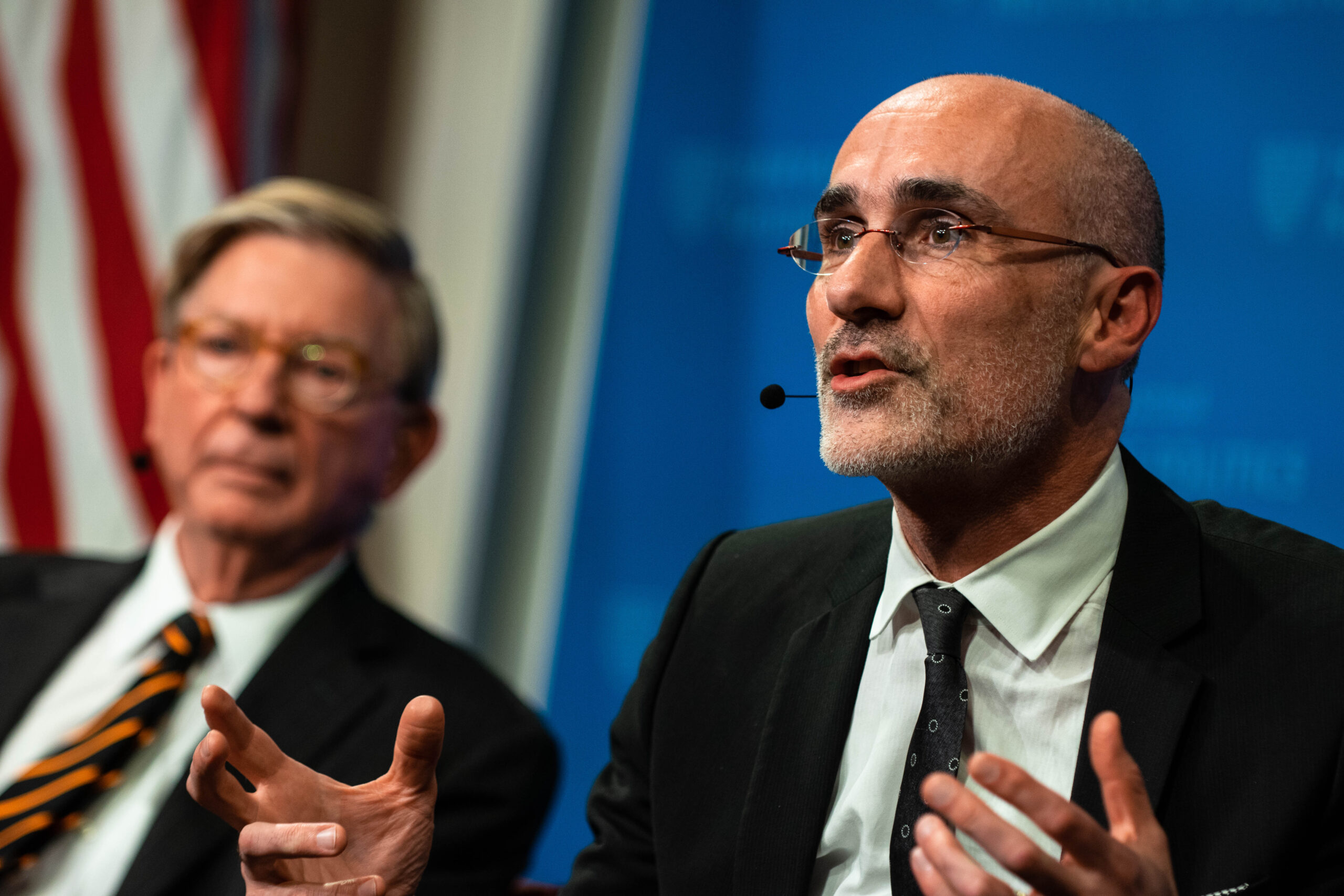

At Harvard Kennedy School, CNN political commentator Alice Stewart (from left) spoke with conservatives Washington Post columnist George Will, Kennedy School Professor Arthur Brooks, and former Arizona Sen. Jeff Flake.

Photos by Sophie Park

The conservative quandary

Leaders of a sidelined political philosophy explain why its principles and goals remain critically important

With President Trump’s courtship of the Republican Party and its brand complete, what does it mean to be a political conservative in this day and age? Well, it’s complicated.

During a talk Wednesday evening at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), Alice Stewart, a CNN political commentator and an Institute of Politics (IOP) fall 2019 fellow, asked a conservative panel from media, academia, and politics to define the values and ideas at the core of the belief system. Each characterized the political and social philosophy quite differently.

George Will, the veteran Washington Post columnist and political commentator, said American conservatism means “conserving a government organized around a belief in natural rights. … Natural rights require a regime of liberty, and the regime of liberty requires a separation of powers. All of which frames the American constant, which is a never-ending debate about the proper scope and actual competence of government.”

Former Republican Sen. Jeff Flake of Arizona said, “Conservatism is achieving the maximum amount of freedom consistent with order,” paraphrasing a famous line from the late Sen. Barry Goldwater’s highly influential 1960 book, “The Conscience of a Conservative.” That has come to manifest itself, in recent decades, in a kind of conservatism that’s animated by “principles of limited government, economic freedom, individual responsibility, free trade, free markets, strong American leadership around the globe,” said Flake, also an IOP fall fellow.

As someone who came to the philosophy after the rise of President Ronald Reagan, and who, like Reagan, strongly favors immigration, Kennedy School Professor Arthur Brooks said he believes conservatism “is open to the embracing of the idea of dignity and potential for ambitious riffraff,” foundational ideas that he hopes one day will define American conservatism once more.

Brooks, a faculty fellow at Harvard Business School and past president of the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, said his conservatism was inspired by something his wife, Ester Munt-Brooks, once said about the U.S. Munt-Brooks came to this country at 25, speaking only Spanish and without a high school education. “She said, ‘This is the greatest country in the world for people who want to work and who want to be free,’” Brooks recounted. “That contains the DNA of what I think this country is all about. This is the ‘optimism for the striver,’ the people who really, truly believe that freedom is possible for all people.”

With Trump in the last several years reshaping conservatism in his own image, Flake said the president is appealing to a diminishing constituency. Flake served in the U.S. Senate from 2013 through 2019 and was one of the few Republicans to criticize Trump publicly.

While a conservative message can attract a broader, more diverse constituency than it now does, the “harsh tone and rhetoric” used by Republican leaders today keeps people away, he said. Suburban women, who polls show have been “walking away” from the Republican Party for some time, are now in “a dead sprint” because of that language, he added.

“Conservatism is achieving the maximum amount of freedom consistent with order,” said Jeff Flake, a former Republican senator from Arizona.

“Are there enough angry people who look like me to sustain a party over time? I don’t think there are,” said Flake, noting that Arizona, close to being a “purple” state, will have a non-white majority within 20 years. “That’s not to say that the conservative movement won’t survive. But will the Republican Party be the vessel of it? I’m not sure.”

Will has been a vociferous “Never Trump” voice on the right and has been highly critical of Republican members of Congress for what he cites as their unwillingness to perform their constitutional oversight. When the nation’s Founders designed the government, he said, they built in a rivalry between the co-equal legislative and executive branches, and they believed that inherent tension would be a reliable check on unfettered power and malfeasance. “Our system is supposed to work even if people don’t have good motives because they have different self-interest,” he said, meaning Congress.

But the Founders didn’t anticipate how political parties would come to exert iron-clad control over not just ideology, but self-identity and all legislative action — and inaction.

“Now that they think of themselves as teammates of the president — and inferior teammates, that he’s the quarterback and they’re interior linemen blocking and tackling for him — the whole script of the Madisonian balance is dissolved,” said Will, a political theorist who briefly taught at Harvard’s Government Department in the mid-1990s.

Discussing the impeachment inquiry, Will said there’s a “vanishingly small” chance Trump will be removed from office. While he suggested that Trump is “guilty of impeachable offenses,” it would be “imprudent” to impeach him so close to the 2020 election, when his base, which polls put at a third of the country, would be convinced that the system was rigged against him.

Brooks advised young conservatives and progressives alike to “stay close to first philosophical principles and not hard party principles … because, in an environment of tribalism, the worst thing that we can do is align ourselves with the party.”

“But that’s not really good enough,” he added. “What we’re talking about is the moral obligation … in a free society … to speak according to our principles and furthermore, to respect the principles of other people, to stand up not just to the people with whom we disagree, but on behalf of those with whom we disagree — standing up to the people with whom we agree. That’s acting according to first principles.”