Mary Bassett discusses the upcoming opioid conference.

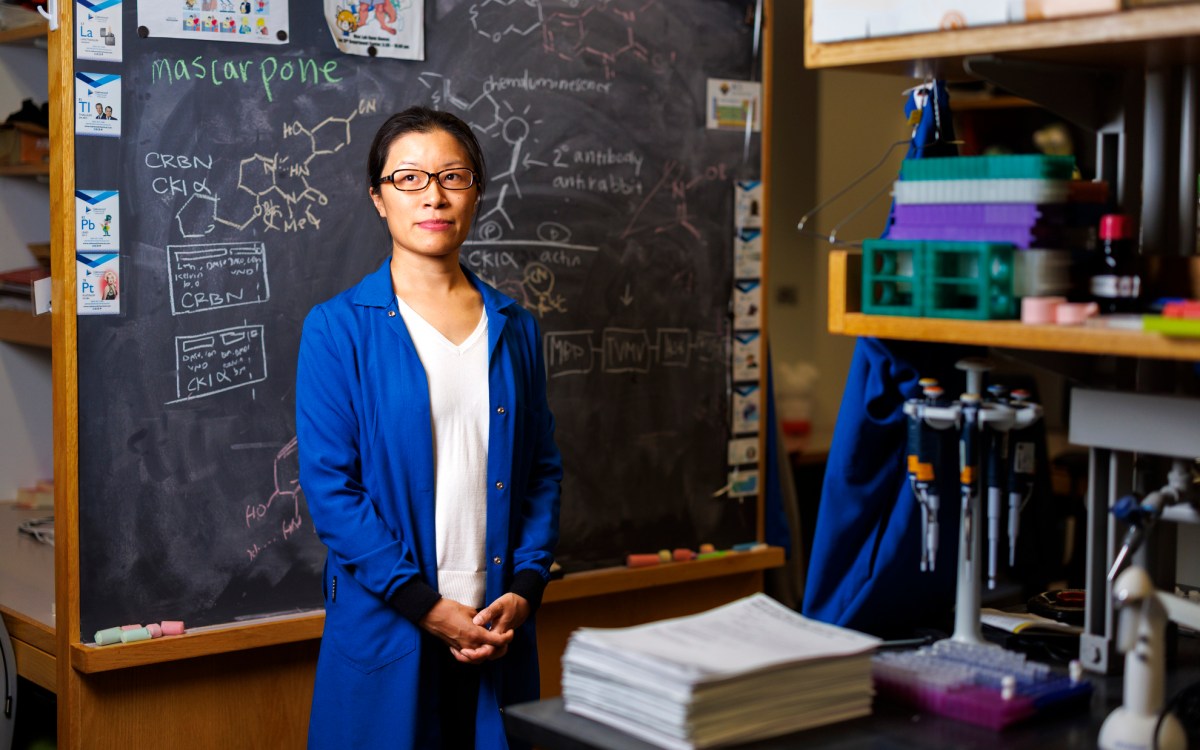

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Specialists take on opioid crisis

Summit to take wide-ranging look at factors of race, stigma, policy, and the lived experience of patients

Harvard and the University of Michigan have joined forces to combat the opioid crisis and are convening this month a summit of scholars, scientists, and practitioners to take a close look at the epidemic of drug use and overdose deaths that has swept the nation. Mary Bassett, director of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s François Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights and the François-Xavier Bagnoud Professor of the Practice of Health and Human Rights, got a close-up view of the epidemic as New York City’s health commissioner for four years. Bassett is the Harvard chair of the meeting, which examines stigma and access to treatment, on Oct. 10 at the Joseph B. Martin Conference Center on Harvard’s Longwood Campus in Boston. Bassett gave an update on the fight to combat overdose deaths nationally and a look ahead to the meeting.

Q&A

Mary Bassett

GAZETTE: Where are we now with the opioid crisis? Have some states started bending the curve of overdose deaths downward?

BASSETT: There is good news. Nationally, we have seen a modest decline, what I would describe as a flattening of the curve of overdose deaths. Overdose deaths in Massachusetts and Michigan are declining, but there are states where deaths are still rising. So, as a nation, we’re seeing fewer lives lost to the opioid crisis — and the data from 2019 look as if that’s been sustained — but there are states still struggling. Really, all of us are still struggling: Massachusetts, where deaths are declining, remains in the top 10 in terms of fatal overdose rates. This is not unusual in public health: We make progress, but there’s still a long way to go.

GAZETTE: What are Massachusetts and Michigan doing that seems to be working that other states could learn from?

BASSETT: The first thing was a prescription-monitoring program, which is an effort to modify the prescribing habits of doctors and other health workers who are allowed to prescribe. It requires doctors to look to see whether or not the patient they’re seeing has other opioid prescriptions. Then there is a direct educational effort to encourage clinicians to prescribe judiciously, to give lower doses for shorter durations. Michigan has pioneered a drug-give back program. One of the ways that people have access to prescription opioids is by “shopping the medicine cabinet” containing leftover pills from prior prescriptions. Both states have been energetic in reducing access to prescriptions. Conversations have come up recently on the other side of the problem, the fact that some providers are responding to the over-prescription of opioids by not prescribing them at all. We should be careful that the pendulum doesn’t swing too far. We don’t want to see patients abandoned or people who have been prescribed opioids and become dependent simply told, “Sorry, we’re no longer going to give them to you.”

GAZETTE: We know overprescribing has been part of this epidemic.

BASSETT: Absolutely, and it’s still the overarching problem. Compared to other wealthy nations, the U.S. is the absolute outlier in the number of opioids prescribed in this century. We’ve seen a quadrupling of prescriptions. This was encouraged by the pharmaceutical industry, which put out this idea in the mid-’90s that pain was the “fifth vital sign” and that no one should feel pain.

GAZETTE: I think with all the coverage of the epidemic, it’s easy to think that all opioids are bad. What kind of pain and what kind of conditions are they still appropriate for?

BASSETT: Opioids are appropriate for people in severe pain, like that of terminal cancer, for example. Instead, people have been given them for all kinds of pain. Those for whom a prescription is no longer appropriate need to be tapered off and should work out a program with their doctors, not be abruptly terminated. There are guidelines emerging that can help. My summit counterpart at the University of Michigan, Chad Brummett, has been very involved in drafting guidelines for the appropriate management of people who are on a high dose of opioids.

GAZETTE: Why don’t we talk about the summit? Who is going to be there and is there a specific audience in mind? Or is the benefit expected to come from the participants networking?

BASSETT: Like all epidemics, we need multiple disciplines in order to address it. There are people from multiple fields attending. In addition to public health and medicine, there will also be lawyers, policymakers, people with lived experience — the intention is to bring a multidisciplinary array of thinkers to the audience. It should include anyone concerned about a broader response to the overdose crisis and willing to engage in a wide-reaching conversation. Our focus is on stigma, which represents an often-underrecognized barrier to effective treatment.

“The character of the response became much more sympathetic and much more accepting of the idea that people who have drug-use problems need help, not punishment.”

GAZETTE: Why is stigma important to look at in some depth here?

BASSETT: Anyone who’s witnessed the current epidemic knows that the response changed when those who bore its burden shifted from largely poor members of communities of color to white, often middle-class, working people. The character of the response became much more sympathetic and much more accepting of the idea that people who have drug-use problems need help, not punishment. This is a good change, though it would have also been good during the heroin epidemic of the ’70s and ’80s, when the response was massively punitive. I think that stigma originates, partly, in how racialized our response to addiction has been. People who use drugs are characterized as irresponsible, just seeking to get high, as people who need to be monitored and punished for their problem drug use.

So stigma is partly due to the history of drug use and the policy response in the United States. Part of it is also due to an enduring belief that people who use drugs have some kind of moral failure. This intensely individualistic society that we live in says everybody’s responsible for where they are. So people who use drugs often feel ashamed — their families are ashamed, too — and aren’t open about their drug use. Health-care workers find people with problem drug use disruptive to their practice, so they aren’t eager to offer treatment, which is also related to stigma. So stigma presents a huge barrier to timely access to effective treatment.

GAZETTE: I see some panels will discuss stigma in different parts of the response, like law enforcement. How can stigma change the response to drug use and overdoses?

BASSETT: Law enforcement has really been a particular example of change. Many senior members of police departments have said, “We can’t arrest our way out of this epidemic,” and that is true. They recognize that the people that they’re encountering need help, need to be directed to treatment, and don’t need to be in the criminal justice system. Many jurisdictions are experimenting, and we’ll hear about some pilot programs at the meeting that basically redirect people away from the criminal justice system. That is really forward thinking on the part of police departments, and I think we have a lot to learn from it. There are other programs where people get arrested and, if they get treatment, their cases won’t be pursued. I prefer to see people never enter the criminal justice system, but there’s no doubt law enforcement is working with public health in ways that they really haven’t before.

GAZETTE: Medication-assisted treatment has been held up as an effective way to help people recover. Is there still resistance to it and is that related to stigma?

BASSETT: The answer to both questions is yes. I just use the term “effective medical treatment” because when we talk about treatment for somebody with diabetes, we don’t call their insulin “medication-assisted treatment.” We have three drugs: methadone, which is highly stigmatized; buprenorphine, which is very underused; and naltrexone. The idea that a person who’s recovered from drug use should not be on medications to be completely “clean” is very, very strong. We need to dispel the idea that somebody who is on effective medical treatment is not in recovery. That person is in recovery: They have their life back; they can hold a job.

We need to reduce the stigma associated with effective medical treatment. It’s pretty close to punishment to be on methadone and you have to go daily for your medication. Buprenorphine providers have to get special waivers. It’s less onerous than it once was, but they can write a prescription for the opioid that makes somebody dependent with nobody looking over their shoulder, but they have to get waivered to prescribe buprenorphine. These are policy questions that should be up for discussion: How do we make access to treatment less extraordinary and more ordinary, just like treating any other chronic disease?

GAZETTE: The general thrust of these medicines is that they treat the craving without the high? So you can go and function, be a parent to your kids, and go to work?

BASSETT: That’s correct. In New York City, we ran a campaign called “Living Proof,” which was a series of testimonials with real people talking about how they were living proof that treatment works. Media campaigns that help destigmatize treatment and show people on treatment, living their lives, are part of the answer to stigma.

GAZETTE: I noticed on the agenda for the summit is a conversation with a patient. Why is it important that someone who’s been through addiction and treatment address this summit?

BASSETT: That’s one of the sessions as we begin the day. I think as we talk about all these facts and figures and show graphs on the whys of the overdose crisis, we should remember that real people have been affected. It’s important to remind ourselves that each one of those numbers is a human being, and that’s what I hope this conversation will do. Of course it takes a special clinician and a special patient to participate in this kind of conversation. It reflects the fact that people who use drugs are really part of the answer to this epidemic and shouldn’t need to hide. Nonetheless, it takes a certain amount of courage to step forward, and I’m very grateful to this individual.