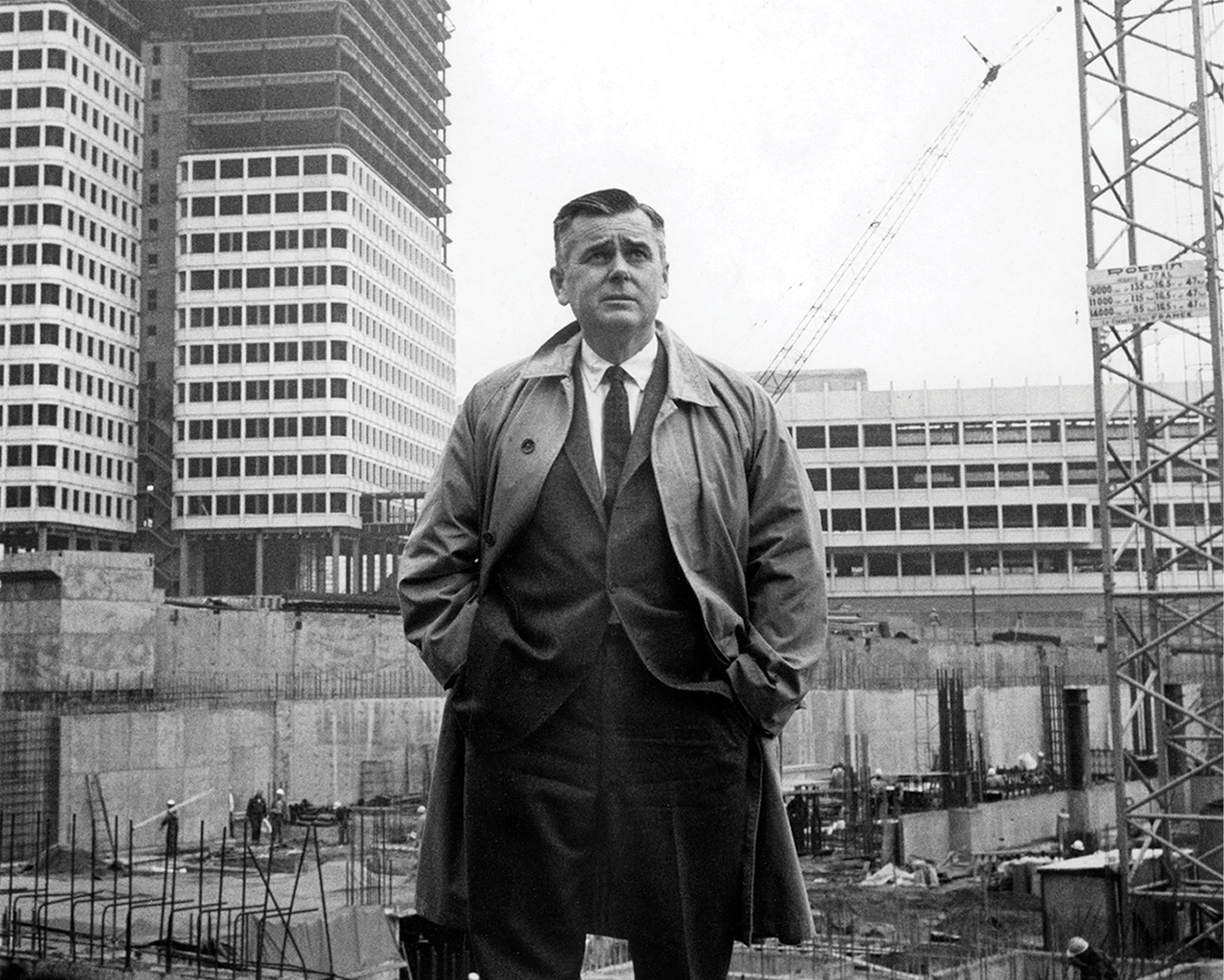

Harvard professor and author Lizabeth Cohen at Government Center, in nearly the same spot urban planner Ed Logue was photographed (below) for Newsweek magazine, April 1965.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Urban planning and social justice

Examining the life and career of Ed Logue, who helped reinvent postwar American cities

In her latest book, “Saving America’s Cities: Ed Logue and the Struggle to Renew Urban America in the Suburban Age,” Harvard historian Lizabeth Cohen examines the life and career of Logue, a Yale-educated lawyer-turned-city-planner who was instrumental in helping reshape and revive a number of declining American cities, including Boston, in the postwar era. As a “die-hard New Deal liberal,” writes Cohen, Logue’s approach to urban renewal was driven by his belief that the federal government had a “fundamental responsibility to address society’s ills.” Logue’s career was peppered with success and failure, but it also was infused with idealism and resourcefulness and offers up important lessons, said Cohen, Howard Mumford Jones Professor of American Studies, dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study from 2011 to 2018, and Radcliffe fellow in 2001. “Perhaps more important than any physical space he built was the kind of committed, experimental spirit that Logue brought to his work, a belief that, as a society we have a responsibility to provide decent housing for all Americans, to make our cities work for all people.”

Q&A

Lizabeth Cohen

GAZETTE: How did you come to write a book about Ed Logue?

cohen: My previous two books were set in cities, but they had not been the focus of my analysis. Over time, I was becoming increasingly interested in the urban built environment and how particular cities grew into what they are today. As a social historian, in my previous work I had largely investigated the experience of groups of ordinary Americans. With this project I set out not just to examine somebody with power in city building, but to bring the categories of analysis that mattered to social history — class, race, occupation, gender — to understanding a person who had great influence. I also wanted to get beyond where I thought postwar urban history was stuck, which was to assume that most of what happened reflected the travesty and tragedy of urban renewal, that American cities had been ruined by the federal government’s imposition of destructive policies in the postwar period. That dynamic was captured in making journalist, author, and activist Jane Jacobs, who was a great critic of urban renewal, into a saint and in villainizing city planner Robert Moses, who participated in it. I felt there was more to this story than those two extremes. Also, I was really interested in finding a way to make this history compelling and accessible, which I felt biography could do. In the course of teaching a Harvard class on Boston history I had discovered Ed Logue, who played a key role in the early history of the Boston Redevelopment Authority and is credited with turning around Boston, a city that was dying in the 1940s and 1950s. I did some digging and discovered that very little had been written about him, though he had left a huge cache of personal papers at Yale, his alma mater.

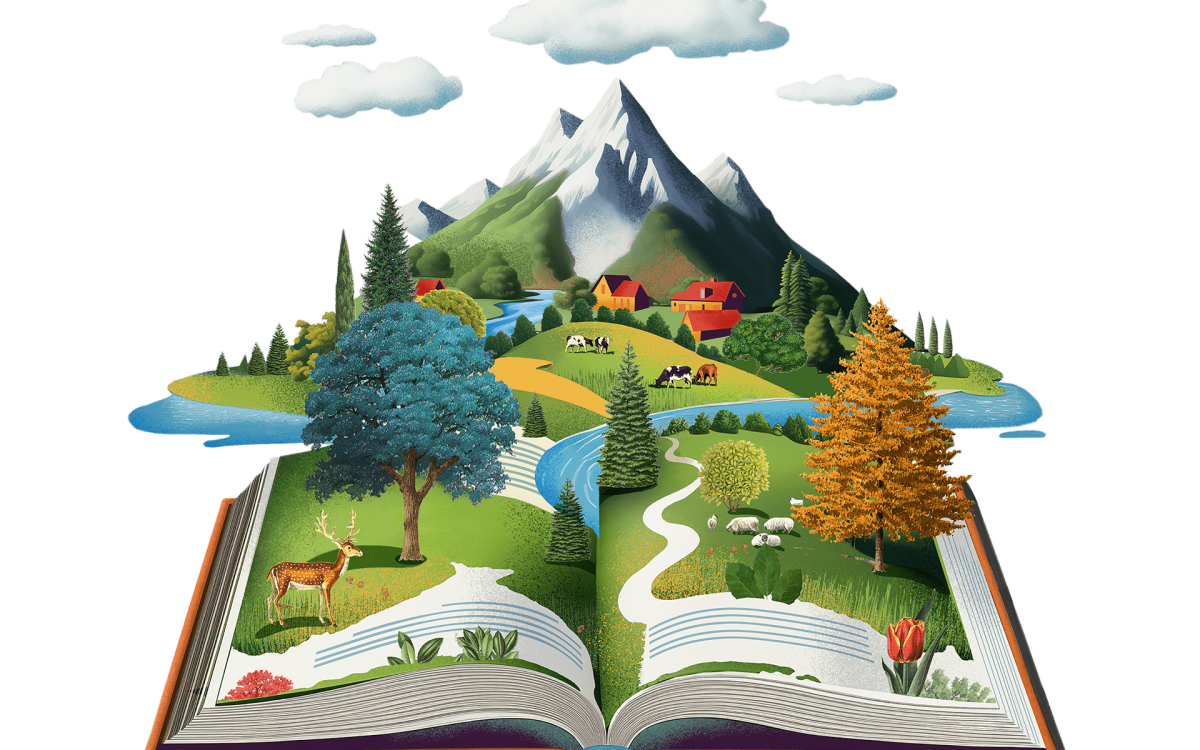

Ed Logue was the force behind Boston’s Government Center (pictured in 1971), which Cohen describes as “…a flawed success.”

Courtesy of Boston City Archives

GAZETTE: Can you give us a little background on Logue?

cohen: Logue’s career in urban redevelopment began in the 1950s, in New Haven. He came to Boston in the 1960s, then he moved on to New York State when Gov. Nelson Rockefeller brought him to head a very powerful, innovative, state-level organization called the New York Urban Development Corporation (UDC). And Logue’s last big job was in the South Bronx. He was a powerful figure whose long career gave me the opportunity to look at a half century of both successful and failed efforts to revitalize American cities.

GAZETTE: He was a brilliant visionary, but he could be harsh with those who disagreed with him or those he didn’t feel were measuring up to his exacting standards. He had a strong sense of his own importance, but he was also devoted to diversity and helping those less fortunate live better lives. Can you say more about his complicated character?

cohen: That’s probably one of the most important points of the book. We miss a lot when we reduce the story to simply Robert Moses versus Jane Jacobs and assume the worst of people who worked to actively revitalize cities that were in terrible shape after World War II. Some urban redevelopers surely were politically corrupt and in the pockets of big business, but Logue wasn’t one of them. His goals were truly progressive. He aimed to bring the activism of the New Deal, which he admired tremendously, to the deep problems of American cities in the postwar period. He believed in empowering the federal government to use its resources and influence to assist cities in coping with the problems brought on by a decade of the Great Depression, followed by the war.

GAZETTE: Why was the period after World War II such an inflection point?

cohen: After World War II there was a terrible housing shortage in the United States, with hundreds of thousands of returning GIs, and many new families being formed. The federal government’s sponsorship of mortgage programs under the Federal Housing Administration and the G.I. Bill famously redlined many urban neighborhoods and encouraged white middle-class families to move into new suburban housing. So cities were not only suffering from deteriorating conditions, they were also grappling with the loss of many residents. In addition, cities that had prospered in the 19th century with industrialization were losing those industries — just as African Americans, desperate to leave the South and build new lives in the North, were arriving in the hopes of finding good industrial jobs. Contrary to many assumptions made about urban renewers, Logue really did have a desire to create cities that were more just and more equitable. He wanted to improve the quality of housing and he learned over time how to do it in ways that didn’t dislocate people. He also sought to create more interracial and mixed-income communities because he recognized that in the United States, where you live determines so many of your opportunities in life. He knew that access to good schools, good transportation, good services depends on whether you live in a community that has the political and social clout to demand and secure those benefits.

GAZETTE: Can you talk more about his work in Boston? In particular about Government Center. Many people today see it as a failure, but at the time many considered it groundbreaking.

cohen: I think that it was a flawed success. It was needed at the time because downtown was not drawing and keeping people in the city. The Yankee business elite for decades had avoided investing in Boston. Scollay Square, which Government Center replaced, was really not a vibrant part of the city. And residents and jobs were moving out — along the new Route 128, for example. So the city had to do something. The hope was for a government center that would bring together federal, state, county, and city agencies and create jobs in the heart of downtown, with spillover effects supporting more commerce and business. In the end, that was what happened. The number of people employed in the area went from approximately 6,000 to 25,000. What Logue did was to use federal dollars as leverage to get others to invest downtown, because he knew that government money alone wouldn’t be enough to turn the area around. I think that the city needed something like Government Center. I don’t think that taking down Scollay Square was a great loss, the way the destruction of the West End immigrant neighborhood had been, before Logue arrived in Boston. But I do think there were mistakes made in the actual design. The plaza just doesn’t work; it’s a very alienating kind of space. Interestingly, some of the historic buildings surrounding Government Center survived because Logue learned over time that it was important to create a city fabric that mixed the historic and the modern.

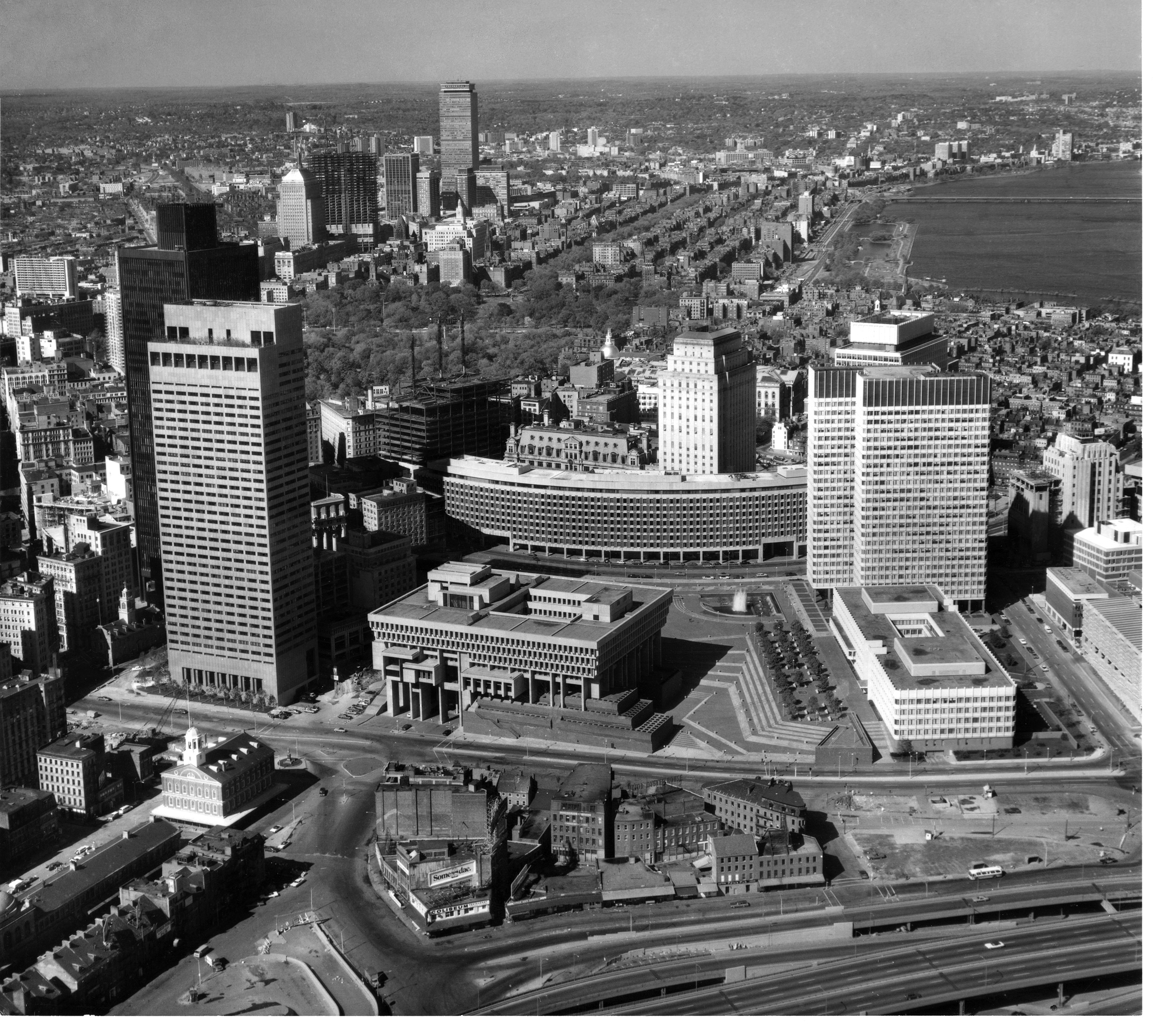

Cohen writes that Roosevelt Island in New York City (pictured) “… is probably [Logue’s] most important project.”

Credit: New York State Urban Development Corp. [Booklet] 1974

GAZETTE: In your opinion, what was Logue’s greatest achievement?

cohen: Physically, I would say that Roosevelt Island in New York City is probably his most important project. I once called it Logue’s “Great Society Utopia in the East River” for his effort to build there a community that was mixed-income, mixed-race, pedestrian-only, and with many other innovative attributes. When its sponsor, the UDC, collapsed, the original plan was never completed, and it eventually attracted market-rate housing that undermined Logue’s original conception. But it’s still a vibrant place that is home to an unusual mix of New Yorkers. It remains affordable for a lot of people, when many other parts of the city are not. But perhaps more important than any physical space he built was the kind of committed, experimental spirit that Logue brought to his work, a belief that, as a society, we have a responsibility to provide decent housing for all Americans, to make our cities work for all people. Logue was also very interested in how architects, if properly encouraged and supported, could help create more decent and affordable housing, applying technological and design innovations to improving quality and supply. And although his main focus was physical renewal, Logue never forgot that people required more than housing, that they needed to make a decent living, and to give their children the best chance at life opportunities.

GAZETTE: His biggest failure?

cohen: I think Logue would have said that it was his disastrous effort to put affordable housing into wealthy Westchester County, N.Y. He thought that finally as head of the UDC, a statewide agency, he was in a good position to engage an entire metropolitan area in solving the huge housing crisis in New York City. (He long had felt that urban problems needed to be addressed on a metropolitan basis, that it wasn’t fair to burden the city alone with the responsibility when suburbanites were earning good livelihoods in the city and then escaping to the suburbs each night.) He thought he had proposed a modest plan to put no more than 100 units of garden apartment-style affordable housing in nine Westchester towns. Boy, did he turn out to be wrong. He was hit with so much opposition that the UDC lost many of its powers and ultimately collapsed. There were other problems as well; sometimes Logue let his ambitions to build override careful financial oversight. But no malfeasance was found. I think Logue was trying to accomplish as much as he could with limited resources.

GAZETTE: What can we learn from him today?

cohen: Logue always insisted that the public sector had to shoulder the major part of the responsibility, that it was not realistic or appropriate to leave big social problems to the private sector to solve. Today, we live in an urban-policy world where the private sector is expected to provide most of the solutions to the affordable housing crisis as well as to other large problems, such as cities’ crumbling infrastructure. We should look at the mess most of our cities are in and recognize that this is not the answer. We have malfunctioning transit systems in major cities like New York and Boston. We have terrible scarcities in affordable housing where nowhere in the United States can someone who works for minimum wage afford a two-bedroom apartment. There’s something wrong here. By turning these responsibilities over to the private sector, we have let private interests dictate too much. I think it’s also a travesty that we have allowed public housing to deteriorate to the point where in many cities the bill for renovating and maintaining it is beyond that city’s capacity, as very little assistance is now coming from the federal government. And yet the lists only grow longer of people who want to get into public housing or to get housing vouchers to take into the private real estate market. Almost all of the solutions that we now embrace depend on the whims of private interests, whether low-income-housing tax credits or opportunity zones that give corporations tax relief, vouchers that can be difficult to get landlords to accept, requirements that developers seeking new market-rate projects pay linkage funds to build affordable housing elsewhere or commit to reserving a certain number of affordable units in their new construction. But we can’t scale these schemes up sufficiently to make enough of a difference.

GAZETTE: So greater public sector involvement is needed?

cohen: Boston’s Seaport District is a testament to what happens when you just let the free market reign, where what is built is what developers think will turn a profit. I’m not saying that we should go back to the bad old days of urban renewal in the 1950s. But we should realize that urban renewal was an evolutionary process that improved over time, and that a person like Ed Logue, who certainly had his faults, did learn on the job. We could use today a bit more of the kind of commitment he showed and his sense that society as a whole, particularly through the resources of its powerful federal government, has to accept responsibility for making urban America more equitable and fair.

Interview was edited for clarity and trimmed for space.