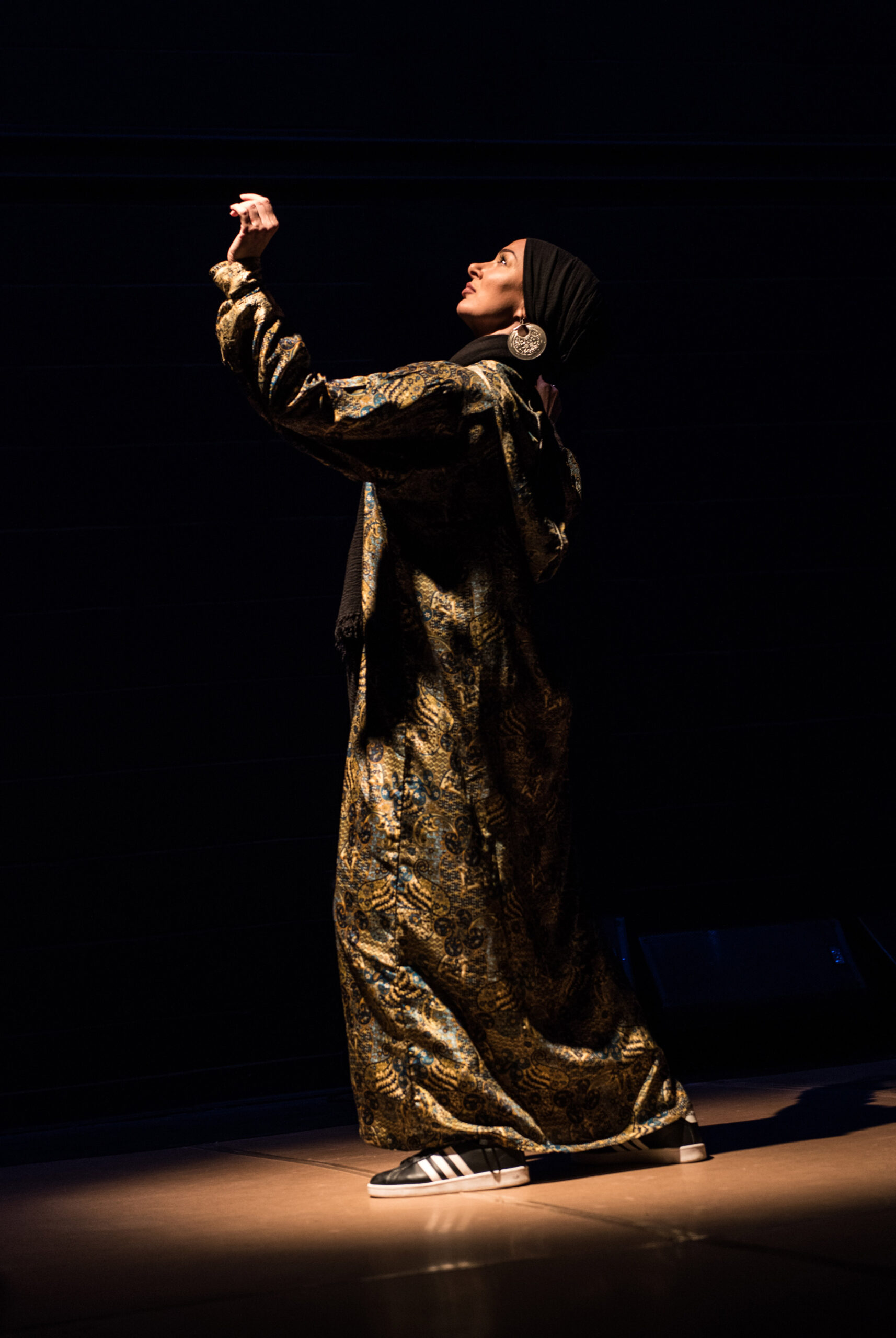

Hip-hop dancer Amirah Sackett discusses the intersection of her activism with her art.

Photo by Melissa Rand

All the right moves

Dancer Amirah Sackett brings her mash-up style to Harvard

Amirah Sackett uses dance to challenge conceptions of Muslim womanhood. The Chicago dancer, choreographer, educator, and activist combines hip-hop with Islamic themes to explore her identity and invites viewers to expand their understanding of movement as a mode of self-expression. During her visit to campus this week, Sackett met with undergraduate students at an ArtsBites session on Wednesday, sponsored by the Office for the Arts. And on Thursday she planned to teach a hip-hop dance master class at the Harvard Dance Center. That session will be free and open to the public. The Gazette spoke to Sackett about the importance of education in the arts, her activism, and love of poetry.

Q&A

Amirah Sackett

GAZETTE: When did you fall in love with dance?

SACKETT: I was a kid who couldn’t sit still. When I heard music, I would just get up and start moving, and from about the age of 7 I was obsessed with learning steps. I have a background in contemporary dance and in classical ballet, and the way that I came to hip-hop was probably first through rap music and the way that it told a story. I loved the way that rap communicated things so efficiently in a short amount of time. I loved, and still love, the music of Rakim, A Tribe Called Quest, Mos Def, Nas. When I started dancing, especially with hip-hop, it was more about mastering skills like breaking and popping. It was around 2011 that I started creating pieces that were more about saying something with that movement. The genre we call hip-hop dance has a rich and expressive movement vocabulary. We have so much to say, and now I’m trying to explore how to translate from what we do in a dance cypher — the circle — to a space like a stage.

GAZETTE: What are some avenues for achieving that translation?

SACKETT: I’ve been fusing Rumi’s poetry with hip-hop and funk beats, and then creating movement with Islamic themes. Rumi has been part of my exploration process in the last few years, and his poetry is popular in the United States, but his Muslim identity is often not discussed here. People are familiar with Rumi as a poet, but they forget that he was also an Islamic scholar. By using Rumi in my work, I’m channeling an artist who is so loved by all and fusing that with hip-hop culture, which I feel is a universal language. I love exploring and growing my skills, but I think it’s very important that I say something with my work.

“I feel that in participating, you have to give respect to your elders. There’s no room for someone to participate in hip-hop culture but hate the people who created it.”

GAZETTE: Have you grappled with any internal tension around embracing hip-hop culture as a practicing Muslim?

SACKETT: There are some aspects of popular hip-hop culture that don’t go hand in hand with my faith, but the area of hip-hop culture that I have always participated in is the hip-hop that operates at the community level, teaching in Boys & Girls Clubs and after-school programs. I did that throughout my early career, and I saw the way that hip-hop culture and expression through dance helps kids get through tough times and deal with difficult emotions and hardships. I don’t think it conflicts with my Muslim identity. I just have to be very choosy about what I participate in and what’s OK for me, according to my beliefs. There are many ways to participate in hip-hop culture.

GAZETTE: What role does education play in your creative practice?

Photos by Gabrielle Mannino and Mary Rafferty

SACKETT: Teaching is a way of learning, which is why I enjoy it so much. It’s also a way for me to honor my mentors and teachers and to share my love of dance. I had a couple of students that I taught at an arts high school in St. Paul, Minn., and they sent me a video of themselves doing the steps they learned in my class, five years later! I have former students who are teaching their own classes, and I was their first contact with dance, and to see them grow is the greatest reward. I travel and teach a lot as well, and it is so interesting to see the way that hip-hop draws in similar kinds of people across borders and languages. And it’s part of black culture, which I am very clear about when I’m teaching the history of hip-hop. We can’t divorce the dance from the people who created it. It’s important for people to know that they’re participating in something that was created by black Americans, and that the struggle of black and brown people in the Bronx is the legacy that they are carrying on when they dance. I feel that in participating, you have to give respect to your elders. There’s no room for someone to participate in hip-hop culture but hate the people who created it.

GAZETTE: You are also an activist and work to counter Islamophobia. How does creativity and activism intersect for you?

SACKETT: Being visibly Muslim, wearing hijab, and doing something as powerful as dance and representing it in this strong way — I think that that image is the complete opposite of what most people who don’t have a lot of contact with Muslims might see. Across the country, I’ve noticed that when I’m able to bridge that gap with dance and art, when I talk about misconceptions about Muslims and our religion, people are more likely to respond to me differently and ask questions they might not ask in a different situation. I think that’s crucial in America, to have the conversations that are uncomfortable and being open to those questions. For me, these kinds of conversations and finding what unifies us is the strongest weapon right now. I don’t want us to be divided; I want us to be unified.