Samantha Power discusses why and how people can make a difference, even from across the globe.

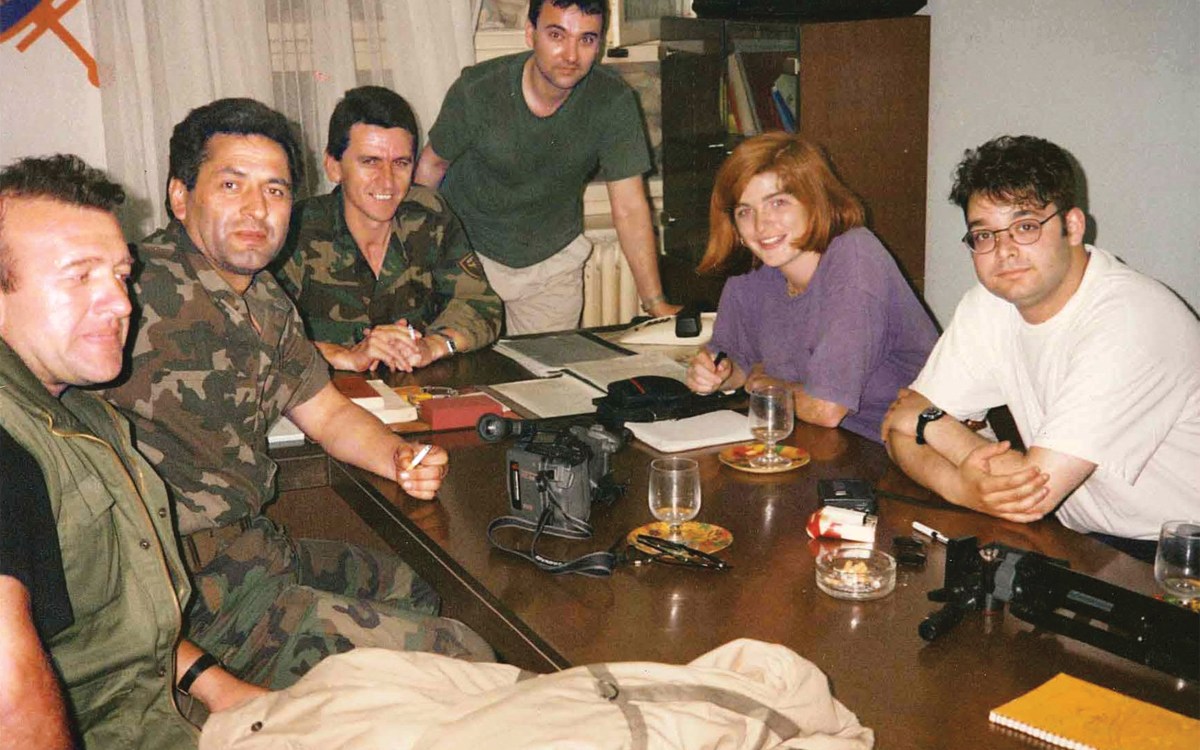

Photo by Martha Stewart

Humanizing global problems

Samantha Power says the desire to make positive change springs from understanding our connections as people

Samantha Power was a child when she moved to the U.S. from Ireland with her family in 1979. Since then, she’s been a war correspondent in Bosnia, National Security official, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, and an academic. And in her new memoir, “The Education of an Idealist,” the Anna Lindh Professor of the Practice of Global Leadership and Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School and the William D. Zabel ’61 Professor of Practice in Human Rights at Harvard Law School chronicles the complications of her life, work, and times. She recently spoke with the Gazette about the importance of trying to make a difference.

Q&A

Samantha Power

GAZETTE: Is it possible to thrive in government and still be an idealist?

POWER: Yes. I think many many people who go into government do so because they don’t like what they are seeing around them. And to me, idealism is simply a word for wanting to try to make positive change. So if you don’t like the fact that our planet is warming, if you don’t like the economic inequality in our society, if you don’t like seeing women working on behalf of human rights being locked up around the world, government is one place you can try to make a difference. There are a set of weighty gravitational pulls toward the status quo that can be frustrating to encounter, but at least what my experience shows is that people with a resilient temperament and rigorous disposition, and perhaps a bit of stubbornness thrown in, can make a profound difference.

GAZETTE: What about journalism? Did your stint as a war correspondent make you hopeful that reporting can be a tool for positive change?

POWER: People can’t change what they don’t know about, and they can’t change what they don’t care about. So what journalists have done from time immemorial is bridge the distance between the lived experience of individuals who may live far away with readers and viewers and others living very, very different lives. I think journalists continue today, despite all of the attacks on the press, to do absolutely essential work for our democracy and continue to hold people accountable, continue to be fact-bound and dedicated to the pursuit of truth at a time when facts and truth are under unprecedented assault. So I think journalists can make an essential difference.

GAZETTE: Why is it so difficult to move people to care about faraway events, even genocide?

POWER: What I hope the book does is show the value of caring, that it’s not a wasted emotion, that to see the individual dignity of people far away or people right up close is an essential prerequisite to ultimately seeing our society head in a more productive and humane direction. I start from the premise that people who are experiencing great difficulty far away are in some sense connected to us. For example, where there is an Ebola epidemic in West Africa, someone can get on an airplane and bring that into our own communities. We’re connected because when someone is burning coal in rural China, that affects our planet in the same way as if someone is burning coal in one’s neighborhood. That doesn’t mean I’m calling on anybody to privilege the lives of people far away more than those of their own loved ones, but I think to recognize that we often have a shared fate is critical to looking out for our loved ones as well.

GAZETTE: You talk about the gulf between the expression “Never again” and the reality that we often do so little to prevent genocide. Is that gulf narrowing?

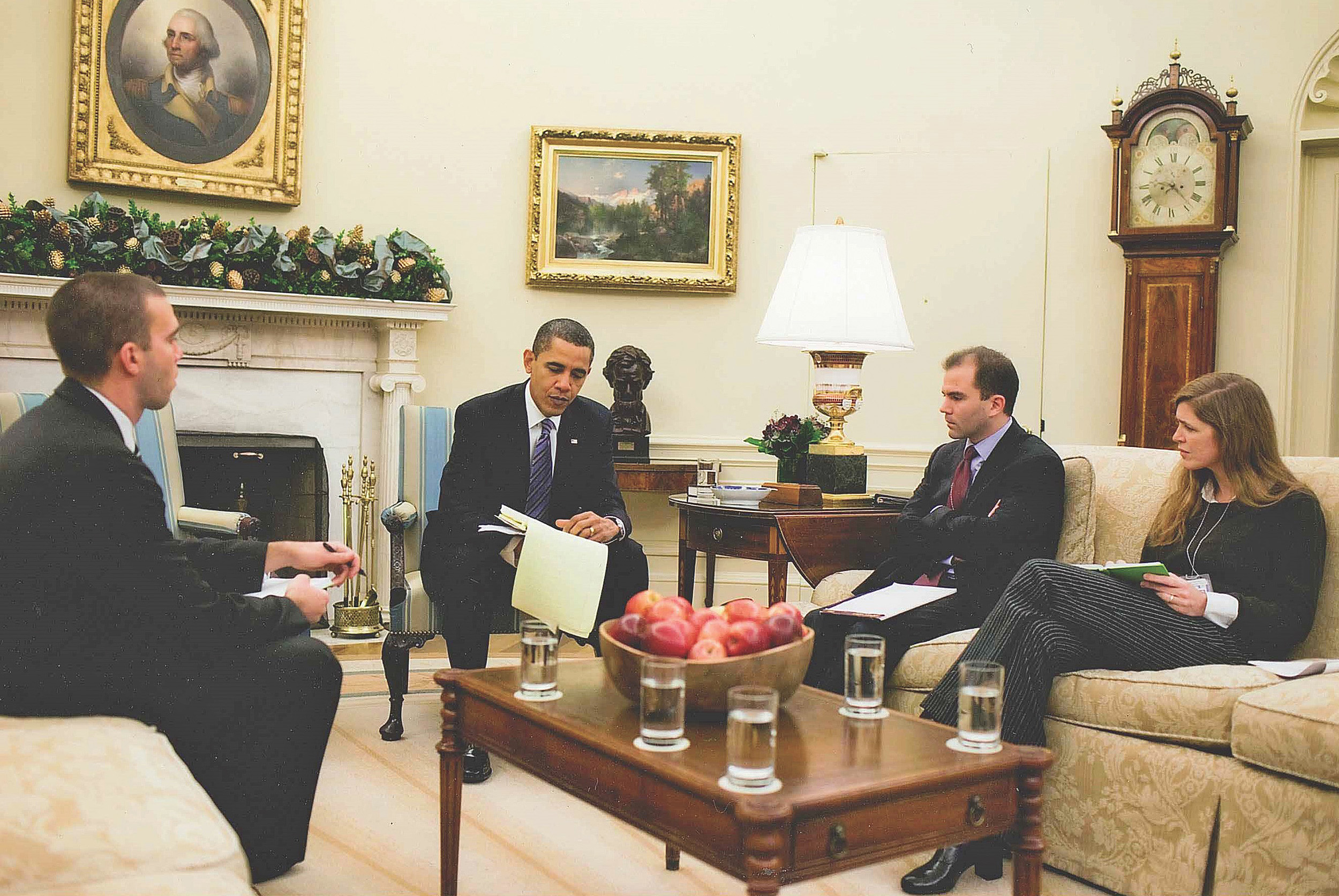

After pulling an all-nighter to work on his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, President Obama summoned Samantha Power and his speechwriters, Jon Favreau and Ben Rhodes, to discuss his new handwritten draft.

Photo by Pete Souza/The Obama White House

POWER: One of the stories I tell in the book is about the steps that President Barack Obama took to prioritize the cause of atrocity prevention. That was really the case I was making in my [2002] book “A Problem From Hell.” It was never my argument that military force was the necessary response to genocide happening far away. Indeed, in most of the cases I discuss in that book, I’m talking about nonmilitary responses that could have saved tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of lives. President Obama elevated the issue, and he ensured that we opened our toolbox and deployed the diplomatic, economic, multilateral United Nations peacekeeping tools in the hopes of making a difference. I think that was a substantiation of the idea “Never again.” Unfortunately, of course, one of the crises that confronted us was Syria. There we employed all the tools short of military force, and yet the atrocities persisted. But I think the fact that the question of how to prevent mass atrocities became center stage really mattered.

GAZETTE: Your book speaks of the “importance of dignity as a historical force.” Can you explain that?

POWER: I was very struck by the way in which, for example, the violation of the dignity of a fruit vendor in Tunisia, that that sense of humiliation, that corruption around him, the fact that he was not seen as an individual, led to him setting himself on fire. And the fact that that single act ended up unleashing a cascade across the Arab world, in part because so many felt that way — that the fat cats who were running their governments were not looking out for the dignity of their citizens. So, too, if you look at our country, at the people who are losing their jobs because those jobs are giving way to automation. Our policies need to see not only the job loss, but what that experience would be like, to go from being able to provide for your family, to have that sense of validation, and then for all of that to be stripped from your identity. That doesn’t give you a ready policy prescription for what you do about automation or job transition, but it reminds you again of the human beings who are at stake when our crippling polarization prevents us from enacting necessary policies. We ignore the ravaging pain of that loss of dignity at our peril.

GAZETTE: Do you worry that fewer and fewer people have a passion for public service?

POWER: I do worry, and that’s one of the reasons I decided to write a memoir rather than a book about foreign policy or human rights. Right now political gridlock and the rage and division in political life is very off-putting for many, as is the fact that you have to raise so much money to run for office, or that when you go into the civil or foreign service right now you’re under attack by the president of the U.S. All of these factors are working against drawing young people and people young at heart into this enterprise. I hope my book opens up what goes on behind the curtain, and it shows the tremendous sense of purpose and meaning you can have. It really tries to humanize the enterprise and show certainly why I found it the most fulfilling chapter of my career up to this point.

GAZETTE: How does writing a memoir rate among the many challenges you have tackled in your life?

“There are a set of weighty gravitational pulls toward the status quo that can be frustrating to encounter, but at least what my experience shows is that people with a resilient temperament and rigorous disposition, and perhaps a bit of stubbornness thrown in, can make a profound difference.”

POWER: I found it immensely challenging to find the right voice, to not sound as if I somehow think I deserve to write a memoir, but rather to show that I’m searching my own journey for insights for myself as well as anybody who might pick up the book. I really wanted to make it as accessible as possible, particularly for young people. To make sure I both had that right tone and that I was just telling a compelling, fast-paced story so that people would want to keep reading, that I found very challenging to get right.

GAZETTE: What inspired you to bring so much of your personal life into the book?

POWER: It was probably motivated by dozens of conversations with students in the time since I left government, where I’ve been really struck by how moved they are by current events, how much they want to get involved and yet how much doubt they have about whether they can make a difference in a world that feels this screwed up. And when they look at me, I was struck at how they see me as the sum of my different stages along my career — so I’m an author, a professor, and an ambassador. That looks so formidable, and yet as it is lived, it is done so with no certainty about what is going to come next. And I thought the more that I can open up my own journey and make it more relatable to people at earlier stages of life, the more likely I think it is that this book will draw some people into believing that they, too, have a role to play.

GAZETTE: A recurring theme of your book is the challenge of figuring out when and how to deploy American power. Do you have a guiding formula for that now?

POWER: I’ve always been a believer that military force is a very very dangerous instrument of American power. There have been times, as in World War II, the Persian Gulf War, and Bosnia, where the use of U.S. military force proved necessary and made horrific situations better. But there are many counterexamples of that, notably the wars in Vietnam and in Iraq. Right now, the military is massively over-extended and the burdens of that over-extension are really borne by a very narrow segment of our population — our military families and the soldiers who are on the front lines. US troops are involved in counterterrorism activities in more than 40 percent of the countries in the world. That’s not sustainable. My only general rule is that [military force] is an extremely blunt instrument. It rarely deals with the underlying structural issues that give rise to conflict in the first place. But there are circumstances in which the benefits outweigh the costs.

Interview was edited for length and clarity.