Life on the ice

Senior scientist Denis Barkats brings equipment back to the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station from the Dark Sector Laboratory.

Credit: Samuel Harrison

Harvard researchers recount working and living at one of the most remote places on Earth: The South Pole

For the scientists who work at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, life at the bottom of the planet is about battling the extreme.

Temperatures never rise above freezing, and can plummet well past 100 degrees below Fahrenheit. Half the year is spent in nonstop sunlight, while the other half is constant night. The area is more than 800 miles from the Antarctic coast, sits atop two miles of vertical ice, and is so dry it’s classified as a desert — the biggest in the world. To top it off, it’s inhospitable to all forms of life and, during the nine-month winter season, the station is cut off from the rest of the world because the fuel that powers the only planes capable of making the trip would freeze into an unusable jelly.

Then there’s the science itself.

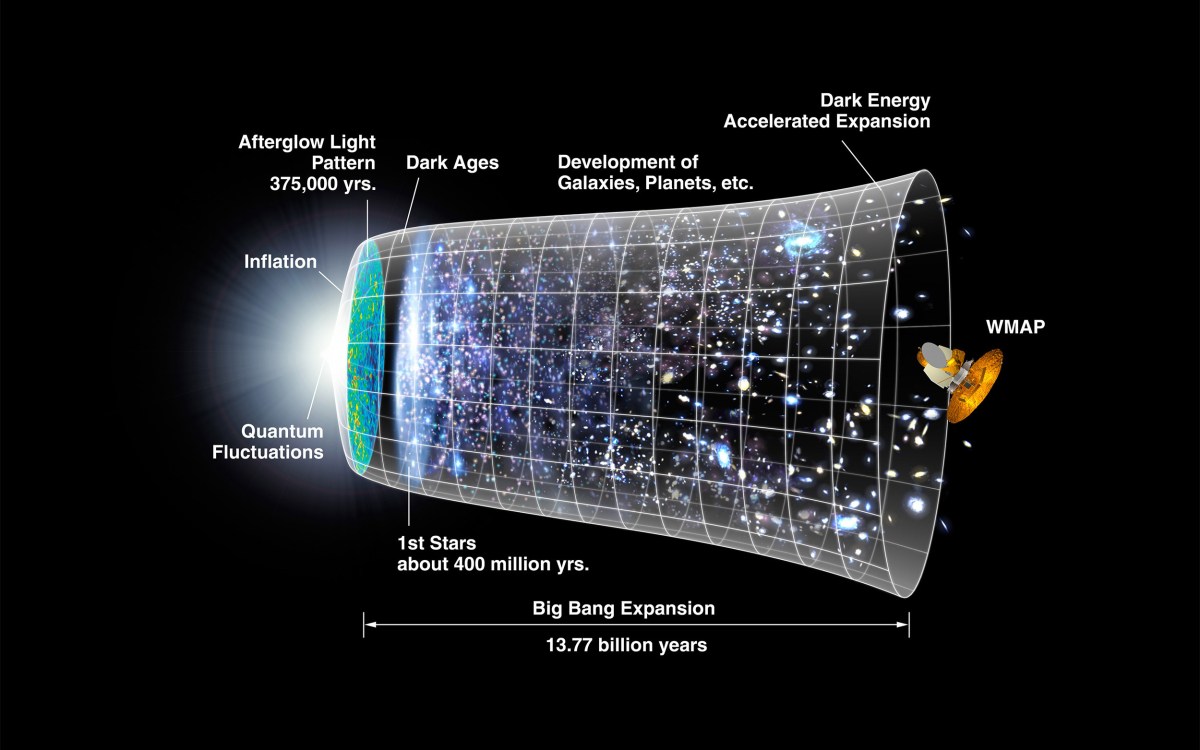

For researchers from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) that means working on a suite of complex microwave telescopes that search the sky for the earliest traces of the Big Bang. A typical week involves workdays in the double digits, six and sometimes seven days a week, because the deadline is tight. The station is only accessible during a three-month window.

Taken together, the jarring environment and limited worktime make the South Pole among the most taxing and isolating work experiences a person can go through, according to seven current and former members of the CfA’s Kovac CMB (Cosmic Microwave Background) Group, which is led by Professor John Kovac and every year sends researchers to the Pole. It’s worth it, they say, because they get an experience relatively few people ever will.

Auroras as seen from the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. The red light marks the telescopes of the Dark Sector Laboratory. Behind them, the early glow of sunrise, still over a month away, can be seen on the horizon.

Credit: Samuel Harrison and Hans Boenish

The southernmost point of the planet is a 9,000-mile journey from Cambridge that can take more than a week. Over the station’s summer season (typically November to mid-February), the group members rotate in and out to work on the BICEP and Keck Array CMB Telescope Experiments. Some stay for a few weeks, others a few months, and a committed handful stay through the winter season (mid-February through October).

Most people will never go. A ticket is at least $45,000, not including equipment, and the Amundsen-Scott station, one of three U.S. research facilities on the continent, is not usually open to tourists. The station’s researchers and support personnel are among the select few who regularly make the journey.

The simple part of the journey is getting to Christchurch, New Zealand, where the U.S. Antarctic program is headquartered. From there, researchers board military planes to McMurdo Station, the U.S. logistical hub built on a bare volcanic rock at the foot of Antarctica. Then they wait. The Air Force isn’t afraid to delay or cancel any number of scheduled flights until there are ideal conditions to reach the Pole.

When the all-clear is finally given, the nearly three-hour flight is breathtaking.

Scientists must cross the Transantarctic Mountains to reach South Pole station high up on the polar plateau. The flight from the coast to the interior of the continent is about five hours on an LC-130 transport plane.

Credit: Samuel Harrison

“It’s probably one of my favorite parts of the journey there,” said James Cornelison, a Ph.D. candidate in astrophysics in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences who is working with the Kovac CMB Group. He’s been down every year since 2016 and in November will leave again for a two-month stay.

The plane, a ski-equipped Lockheed LC-130, soars above a featureless ice shelf, he said, then over the Transantarctic Mountains before rising up to the Antarctic Plateau, a sheet of ice more than 9,000 feet thick. It lands on a runway made of ice and snow.

Samuel Harrison ’12, a former research scientist and mechanical engineer with the group who in the last five years has spent more than 15 months at the Pole, described it best: “As you’re crossing the Transantarctic Mountains, you look below you and there’s just these amazing glaciers where the ice is essentially flowing off the continent down through the mountain range out to the ocean. You just see the height difference between zero elevation and 10,000 feet of snow [and ice]. When you get up to the plateau the mountains basically disappear because the snow [and ice] is as high as the mountains.”

Initial shock

Researchers get an environmental reality check as soon as they touch down.

The cold hits them right away, freezing their nose hairs. The average temperature during the summer season is 18 degrees below Fahrenheit — which Boston reached just once, on the coldest day in its recorded history. The next thing most of the scientists notice is the brightness. The sun is on a 24-hour loop around the horizon, the sky is an intense blue, and the snow reflects all the light back up, blinding and disorienting them.

“It’s like stepping off on a new planet,” said Denis Barkats, a senior scientist on the team. “All of your human environment bearings are off.”

Robert Schwarz has wintered at the South Pole a record 15 times. Pictured here with his winter breathing mask.

Credit: Samuel Harrison

Some feel dizzy, even sick, right away because of the elevation and because of how incredibly dry the air is. The Antarctic desert, where the Pole is located, is the largest, driest, and windiest desert on Earth.

All that hits some researchers hard. Some take a snowmobile the roughly 100 meters from the runway to the squat, metallic-colored station, which is elevated above the ice, because they can’t make the walk on their own. Others aren’t affected, or at least not immediately. Eventually, it catches everyone, said Barkats, who’s spent more than 28 months at the Pole over eight trips.

“Within a few hours you start feeling the effects of altitude,” he said. “Even if it’s not severe, you do feel it. You walk up some stairs and you feel dizzy or out of breath. And then again, within a few hours, you start feeling the effects of the dry atmosphere. Your mouth is dry. Your nose is dry. Then with the combination of the dry air and the high altitude, you drink a lot so you’re peeing all the time,” he said, laughing.

The station community

After arriving, the scientists get a chance to settle in. The station has a gym, greenhouse, movie room, music room, rock-climbing wall, and even a sauna, which make up for some of the isolation there, since internet access and the chance to speak with family and friends is limited to the two to four hours when communication satellites pass overhead.

But they do have the community at the station.

“I find the people aspect of my stay there to be very enriching and interesting,” said Marion Dierickx ’12, A.M. ’14., Ph.D. ’17, one of the CMB Group’s postdoctoral scholars.

Amundsen-Scott Station, which is the third iteration of the original 1956 complex, houses about 150 people in the summer and 50 during the winter. Along with astronomers and astrophysicists, scientists travel there to study particle physics, solar energy, geology, glaciology, and climatology. There are also cooks, plumbers, doctors, internet technicians, electricians, and others who help keep the station running.

“I always joke that I live in Boston and it’s a city of 3 million people but I actually socialize more and meet more people when I’m at the South Pole.”

Marion Dierickx

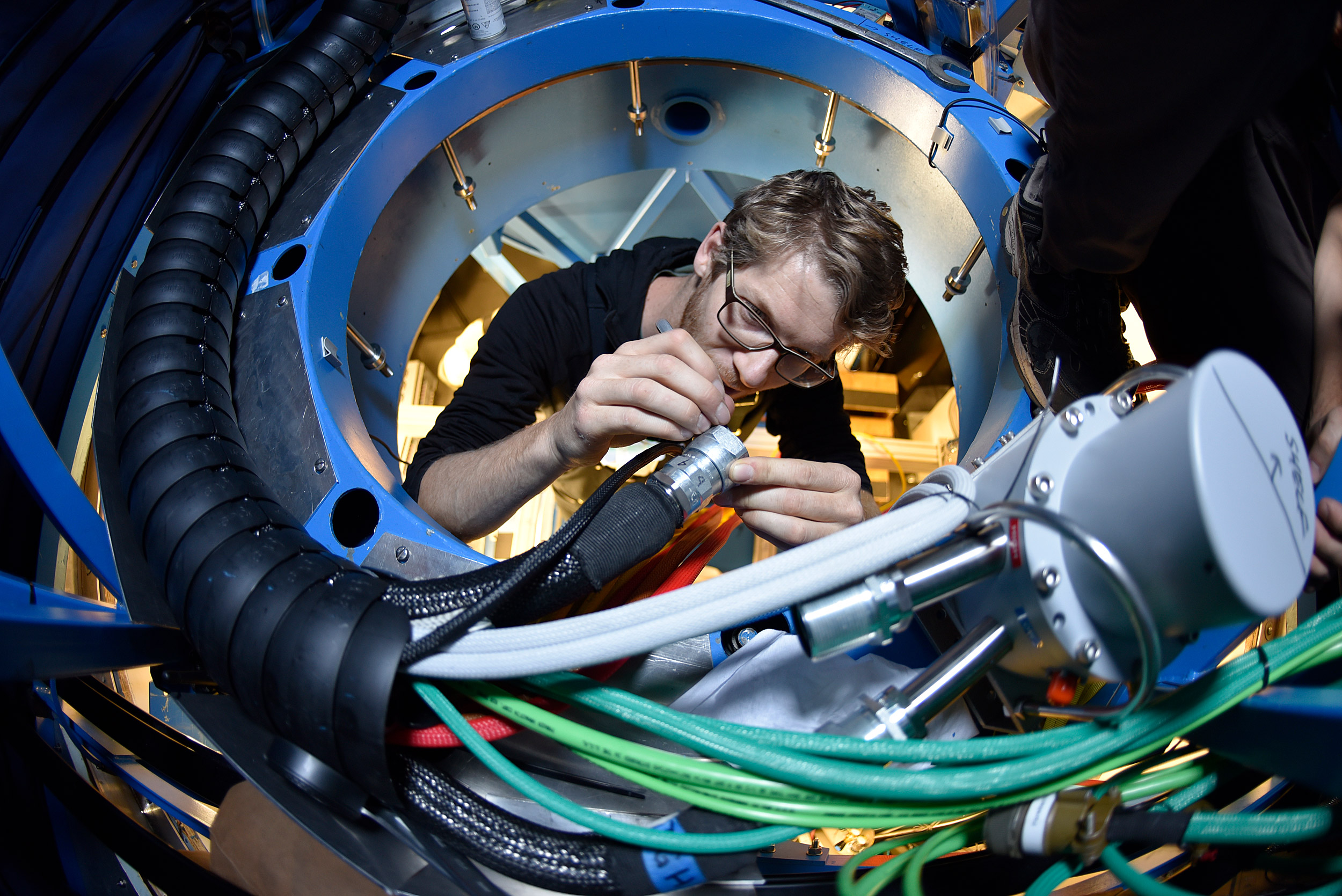

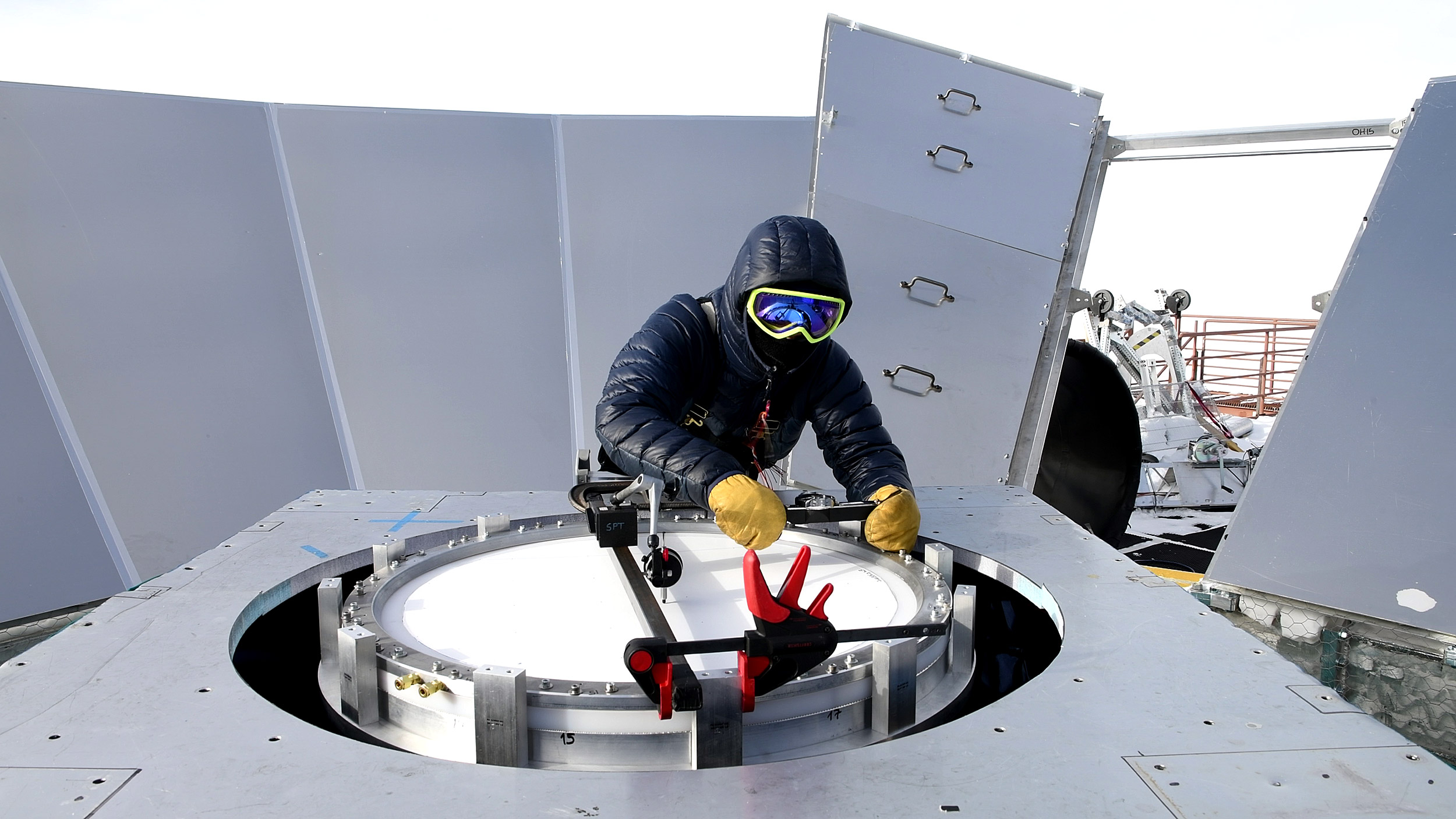

Installing a new vacuum window on the BICEP3 Telescope.

Credit: Samuel Harrison

“The people who end up at the South Pole are not just your average person,” Dierickx said. “They tend to be people who are maybe a little bit eccentric but definitely have a sense of adventure. People who’ve led interesting lives, who’ve had all sorts of unusual trajectories and experiences. The proportion of the station population who are outdoor adventurers and have traveled the world is extremely high, so you sit down with anybody over a meal and you’re talking about that time when they soloed across some crazy mountain range in Alaska or whatever — that’s just your normal dinner conversation at the South Pole.”

Many of the researchers who spoke with the Gazette described the group as the most welcoming and tight-knit they’ve been a part of. “I always joke that I live in Boston and it’s a city of 3 million people but I actually socialize more and meet more people when I’m at the South Pole,” Dierickx said.

People form bands, and pick-up basketball sides. They organize trivia nights. They celebrate birthdays and holidays like Thanksgiving and Christmas. And the station is replete with its own traditions, carried on season after season.

Some are ceremonial, like the unveiling of the new South Pole marker, a location that shifts about 20 meters every year because the station sits atop a moving ice shelf. The marker is designed by the previous year’s “winter-overs.”

Samuel Harrison leaves Dark Sector Laboratory in a whiteout. BICEP3 Telescope on the right, South Pole Telescope on the left.

Credit: Samuel Harrison

One is horror: After the last plane takes off for nine months, the winter crew watches “The Thing” and “The Shining,” whose characters are also isolated from the world by winter conditions. There’s the “Race Around the World,” a three-lap, two-mile race around every line of longitude on the planet.

And one is bizarre: baking in the station’s sauna at 200 degrees Fahrenheit and then running outside to touch the South Pole marker in a bathing suit. In the winter, when temperatures reach below 100 degrees, it becomes the “300 Club” in honor of the temperature range, and they do it in nothing but their boots.

“The sensation is amazing,” Barkats said. “Your brain tells you, ‘You should be freezing,’ because you know it’s negative-100 degrees outside, and yet your body has accumulated enough heat that you actually feel quite comfortable for three to five minutes. I did it during my winter and it was so incredible, I repeated it immediately afterwards.”

‘Space’ walks

Besides that bit of fun, going out in the cold is serious business. All personnel are issued extreme cold weather gear by the National Science Foundation, which oversees the Antarctic program. The outfit includes a big red parka, overalls, goggles, three layers of gloves, heavy pants, large boots, and many more layers. It adds up to about 20 pounds of clothing and takes about 10 minutes to pull on. Many of the researchers say they feel like astronauts once they’re prepared for the outdoors.

The gear is so effective that it does more than cancel out the cold. Some of the scientists admitted they felt too hot when they were outside. In fact, there were times they went without some of it.

Denis Barkats stands in front of a sundog, a phenomenon created by sunlight refracting through hexagonal ice crystals in the air.

Credit: Samuel Harrison

“I actually felt colder during the winter in Boston a couple of times than I ever felt being outside there,” said Kate Alexander, A.M. ’14, Ph.D. ’18, who spent December 2015 at the Pole as a grad student.

But the freedom to skip a layer only lasts for the summer, when the temperatures linger at about 20 degrees below zero. In winter, all gear is necessary and they must be absolutely rigorous putting it on. Any exposed skin can be frostbitten in less than five minutes.

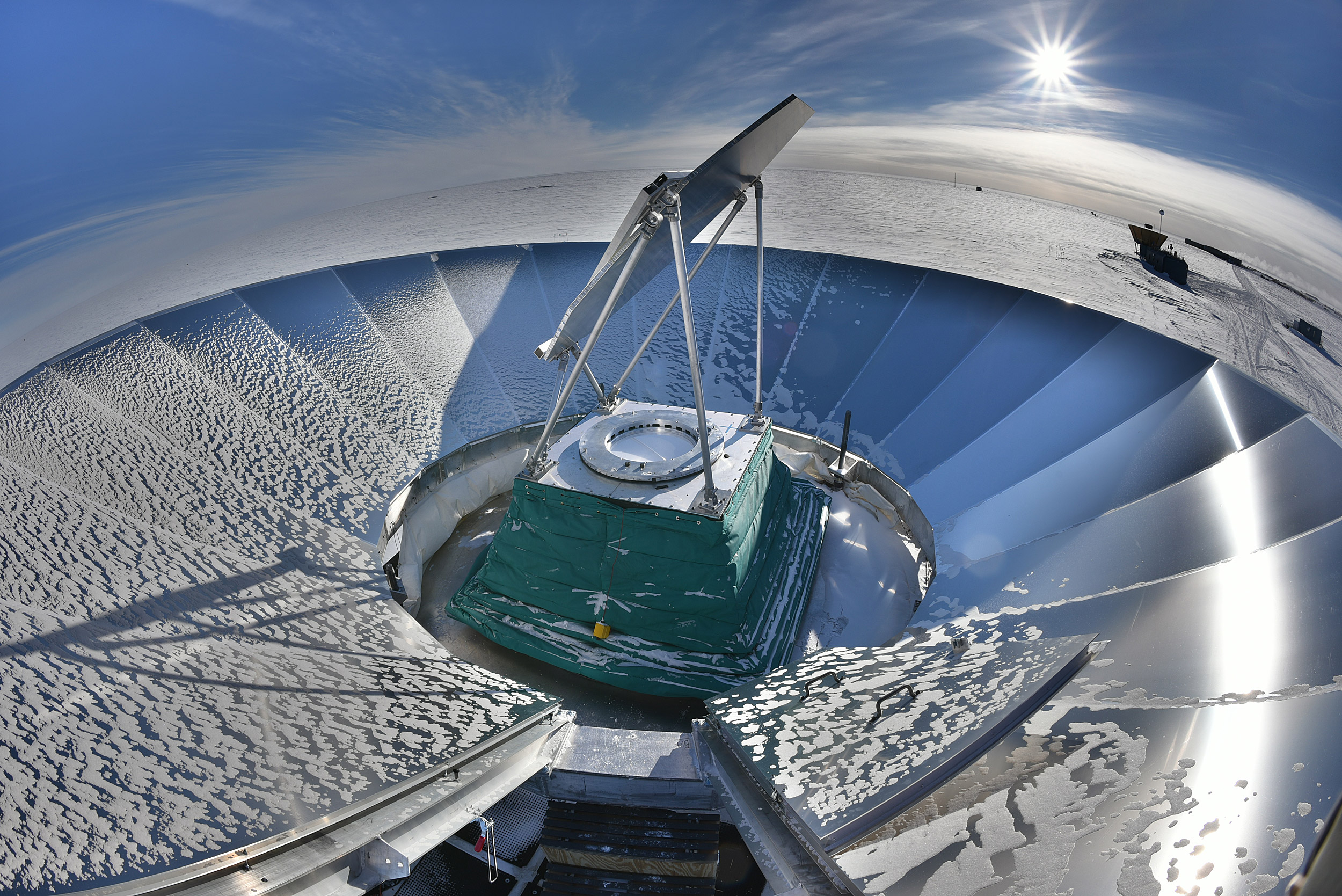

BICEP3, the current version of the BICEP telescope, and the Keck Array telescopes are about a kilometer away from Amundsen-Scott’s main living facility, in what’s called the Dark Sector laboratories. To get there, researchers follow an orange flag-line out in the frozen plains. It’s about a 15-minute walk each time they have to go back and forth, which is usually about four times a day.

The landscape is stark and unchanging. Besides the main station and nearby research facilities, there is nothing but open sky and snow that squeaks like Styrofoam underfoot. The weather is fairly calm, but there is wind that is able to carry the snow — which behaves more like sand because of the extreme cold and dry — scattering dune formations across the empty expanse.

“When you look out from the station, depending on the time of day, you could totally imagine that you are on the ocean.”

Samuel Harrison

Dune-like formations sculpted by the wind called Sastrugi cast shadows on the ice as sunset approaches.

Credit: Samuel Harrison

“You have these little waves that are sculpted by the wind in the surface of the snow,” said Harrison, the mechanical engineer. “When you look out from the station, depending on the time of day, you could totally imagine that you are on the ocean.”

Another casual summer sight are the solar displays formed as ice crystals in the air reflect the sunlight, creating arcs, halos, and spots around the sun.

Go, go, go

The CfA researchers have only about three months to get to the Pole, make routine upgrades like yearly calibrations or swapping out broken or damaged pieces, complete major overhauls such as replacing entire telescopes, and leave. Any longer, and they are trapped.

“It creates this urgent tempo,” said Cornelison, the grad student. “Every minute that you spend doing something recreational is a minute that you’re not spending accomplishing your job. Your standards for what a good work-life balance is change. It’s not abnormal to wake up at 5 or 6 in the morning and get some work done before breakfast and then work until lunch and then work from lunch until dinner and then after dinner you go back out to the telescopes and work. So every once in a while, you’ll find yourself working 14 to 16 hours and then you go back to the station, you sleep, you wake up, and you do it all over again.”

The hustle only intensifies as mid-February approaches, but it also creates a sense of focus at the station since everyone is working under the same hard deadline. It’s also why the work is planned months ahead, before the group even leaves Cambridge.

Marion Dierickx and Samuel Harrison operate the BICEP3 Telescope from inside the Dark Sector Laboratory.

Credit: Samuel Harrison

The work is exacting. The telescopes are a complicated mix of electronics, optics, control systems, motors, and detectors inside a large cylinder placed on a moveable mount inside the observatory. The detectors in the telescopes must be kept at about a quarter of a degree above absolute zero, and they require a vacuum chamber that uses a cryogenic system to keep them super-cooled.

With work that precise, things often go wrong. Parts sometimes don’t fit, or don’t work. Sometimes the scientists need equipment that’s back in Cambridge or in the labs of one of the institutions the Kovac CMB Group collaborates with, which include the California Institute of Technology, Stanford University, and University of Minnesota. When this happens, the team has to improvise with what’s on hand, often visiting the “graveyard” for spare parts and welding them pieces to force a fit. Other times they find a tool or material — even dental floss — that can be an effective substitute for whatever they need.

It all begs the question of why the telescopes are there in the first place.

The answer is as big as the Big Bang.

The extremely dry environment at the South Pole limits contamination to the data collected by the telescopes, as water molecules absorb microwave energy. In addition, the site provides unobstructed views of a particular patch of space, since the sky above the Pole never sets, it only rotates.

Together, these factors make the South Pole the ideal place to look for the tiny signals from primordial gravitational waves that were generated during inflation, fractions of a second after the universe began.

The winter

After the last plane takes off, it leaves behind a skeleton crew of about 50 people.

“You’re left there and you’re it. You’re the person to run it,” said Barkats, who wintered at the Pole from the end of 2005 to 2006, spending a total of 12 consecutive months there. “Your job is to avoid downtime.”

Sometimes that’s easy.

“These are really complicated instruments with a lot of moving parts and different subsystems, so things are always needing help, whether that’s servers running out of space or helium pressure needing to be topped off,” Harrison said. “It’s just like a car — things break down when they’re being used.”

Harrison over-wintered in 2015, spending almost a year on the ice. It was the first time the BICEP3 telescope was deployed, so he kept busy trying to get it to work as designed.

“I effectively lived alone out in the [Dark Sector] lab working all day, every day for nine months,” he said. “Depending on the state of the telescope I would often need to stay out there for multiple days.”

At other times, Harrison and Barkats said they got into a rhythm: communicating with friends and family at home when they could, planning the next week’s goal with colleagues back in Cambridge, taking walks, and participating in game nights with other winter-overs.

Although Amundsen-Scott Station is completely self-sufficient, even growing its own vegetables in the greenhouse, the Pole’s true isolation hits in winter. If something were to happen, the crew is on their own; rescue is almost impossible because of the cold, the darkness, and the gale force that can come at any time. Yet there have been only three winter evacuations since the station was established. In 1999, a doctor who discovered she had breast cancer treated herself for almost six months, performing her own biopsy and administering her own chemotherapy until a rescue plane was cleared for takeoff.

None of it is enough to keep people from the outdoors, which fills with stars and colors easy to get lost in after the sun goes down.

The BICEP3 Telescope makes observations about a week before sunrise. The Keck Array Telescope and the Amundsen-Scott Station are in the distance.

Credit: Han Beonish

“Sunset at the South Pole is something that very few people have ever experienced,” said Harrison. “It is more of a process than a moment.” It happens over a matter of weeks, starting near the end of February and going to the end of March. Over that time, the sun gradually moves closer and closer to the horizon, skimming the edge and becoming distorted as the light bends through the atmosphere before it disappears.

What’s left isn’t darkness. Small streaks of purple sliver out from the opposite horizon and slowly take over the entire sky. When that’s gone, stars come out in droves. “Incredible,” Harrison said. “Horizon to horizon, no light pollution, so clear that you can see individual gas clouds in the central regions of the galaxy with the naked eye.”

Then come the auroras, which most often appear as swaying curtains of green light moving across the deep night sky. They can also be red, purple, or white.

“They are mesmerizing rivers in the sky,” said Barkats. “They move and dance and bounce and change, sometimes slowly, sometimes fast. Sometimes I would walk from the station to the telescope, a 25-minute walk fully geared up, with my hood and goggles giving me this tunnel vision, when suddenly I would wonder why the snow was glowing green. How odd. Then I’d lift my head up and would see a firework of light and color in the sky. Although I’m a physicist and I fully understand the phenomena causing auroras, I still had shivers and felt a sense of awe and wonder.”

Sunrise, Harrison and Barkats said, is a perfect reversal of sunset, and it signals they are soon to leave their adopted home.

“By this point you have been in isolation for over seven months and there is tremendous anticipation,” Harrison said.

“It’s like being an adult, but being born again. You discover all of the wonders of life that you’ve forgotten.”

Denis Barkats, on returning home

No matter how beautiful, winter isn’t for everyone. Dierickx, the postdoctoral fellow, originally accepted the post hoping she would get to winter over, but after two trips in the summer season she reconsidered.

“I realized that to me the prospect of spending a whole year in that same tiny spot on the map is very forbidding in the sense that the South Pole is a complete arbitrary location,” she said. “There is nowhere to go from there. The idea of spending a whole year there is a huge opportunity cost for all the other things I could be living and experiencing elsewhere in the world. I think to me it would feel like a prison.”

Going home

Dierickx, who will travel to the Pole again this summer, wasn’t alone among the researchers the Gazette spoke with in feeling that the Pole’s warmer months are enough for them. By the end of this upcoming season, Dierickx is sure she’ll be ready to go home again.

“There’s a pretty consistent trend that when you land there you’re bright-eyed and bushy-tailed and you’re happy and you’re ready to put in all this effort and work,” said Tyler St. Germaine, who has visited the station for two-month stays four times in as many years.

“You’re full of energy and you’re full of optimism,” said St. Germaine, who will earn his Ph.D. in astrophysics at the end of the academic year. “But almost every time, by the time your six or eight weeks are up, your last week or two you’re like, ‘I’m ready to go home. I miss my family. I miss my internet. I miss my friends. I want to breathe air again. I want to experience the real world. I want to get out of this place.’”

Luckily, the shock of returning is always a pleasant one, and comes with a new if temporary appreciation for some of the best features of modern life.

“It’s like being an adult, but being born again,” Barkats said. “You discover all of the wonders of life that you’ve forgotten how awesome everything was. It’s raining! That’s fantastic. You’re seeing animals. You’re seeing babies. You’re going to a restaurant. You have this sudden choice among so many different foods that you can eat.

“To me, that very first month that I was back in New Zealand, all of those little quirks that make life amazing just became very acute and I was super impressed by everything. I thought life was wonderful. But then you forget. It smooths out and the routine of life catches back onto you.”

The team is currently preparing to deploy the newest telescope in the series called the BICEP Array this coming summer season.

The research being conducted by the Kovac CMB Group and the United States Antarctic Program is funded by the National Science Foundation.