Cuban guerrilla leader Fidel Castro does some reading while at his rebel base in Cuba’s Sierra Maestra mountains in this 1957 photo.

Andrew St. George/AP Photo

Portrait of the revolutionary as a young man

How Jonathan Hansen’s persistence gained him access to people and papers of ‘Young Castro’

When Jonathan M. Hansen decided to write a biography of Fidel Castro’s early years, he hoped to “get past the demonization and celebration and recover the complex person in the middle.”

“Biographers and historians on both poles have treated his life like prosecutors scouring his past to find evidence to convict a guy we don’t like,” said Hansen, senior lecturer on social studies and faculty associate at the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. “This, to me, makes for bad history and disappointing biography.”

In researching “Young Castro: The Making of a Revolutionary,” Hansen followed the educator’s proverb: “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” He was relentless in his pursuit of archival documents and gained the trust of dozens of Cubans who knew Castro.

The author of “Guantanamo: An American History”and “The Lost Promise of Patriotism: Debating American Identity, 1890‒1920,” Hansen discussed the challenge of accessing Castro’s papers, meeting one of the women he loved, and the privilege that imbues American thinking about the island nation.

Q&A

Jonathan M. Hansen

GAZETTE: Why a biography?

HANSEN: My last book on the history of Guantanamo naval base didn’t sell, despite being the definitive book on the subject. What sells? Biographies, obviously, and at the suggestion of my literary agent, I began to flirt with a Castro biography, focusing specifically on his younger years.

GAZETTE: Why the younger years?

HANSEN: Because treatment of those years are the least satisfying in the existing literature. Biographies are a little out of fashion among academics, but I try to set Castro very much in his context and in the context of the problems of the century in which he lived. In other words, I use biography to make larger historical arguments and teach the public things they might otherwise shy away from.

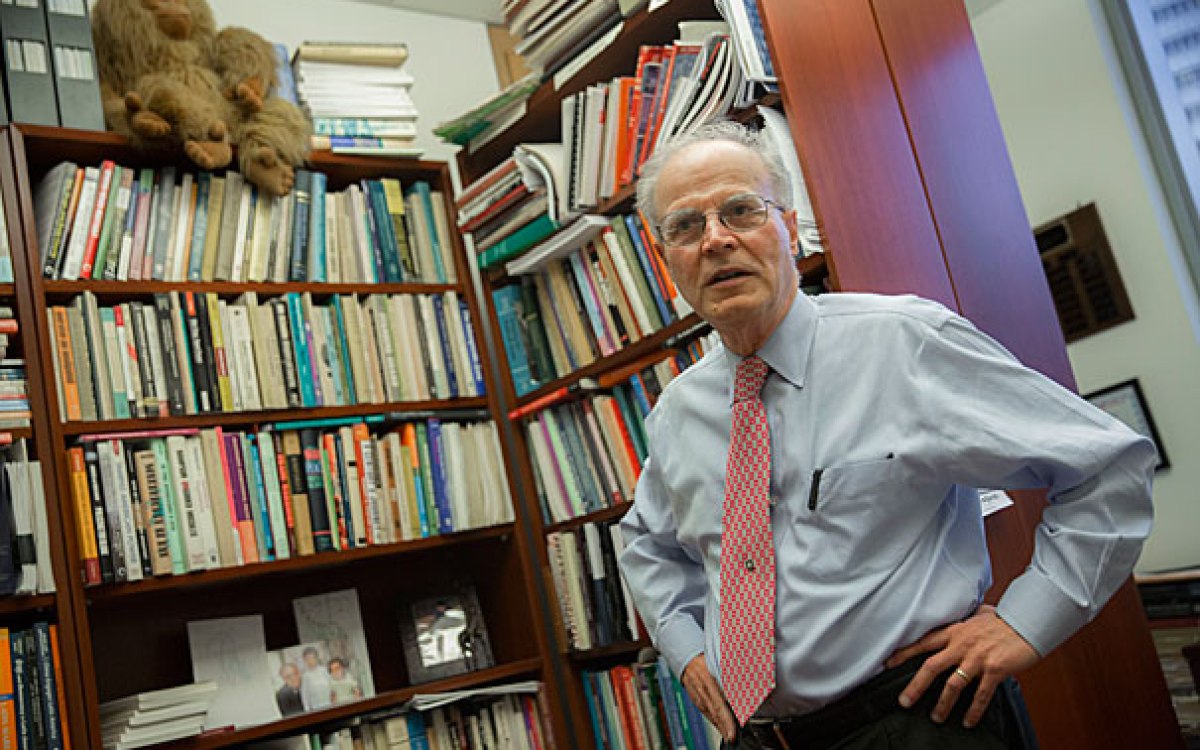

Jonathan M. Hansen is the author of “Young Castro: The Making of a Revolutionary.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

GAZETTE: You interviewed many people with personal ties to Castro who had never spoken publicly before. How did you get them to open up, and what was at stake for them?

HANSEN: You can imagine that it wasn’t easy for a blond-haired, blue-eyed devil like me to get access to the Castro archives. There hasn’t been a Castro biographer from the United States admitted to the Office of Historical Affairs of the Council of State (the sanctum sanctorum of Castro studies) since Tad Szulc wrote his biography more than a generation ago. And Szulc used the archive mostly to conduct interviews. By contrast, I was permitted to photograph the entire Castro papers, which stretch from long before his birth through the triumph of the revolution and include countless letters, of course, but also such things as school and university transcripts and gas station receipts from his frenetic political activity. The collection comprises thousands of pages. Starting in early 2013, I began to knock on the door of Cuba’s leading research institutions. Speaking rudimentary Spanish and bearing an assortment of modest gifts (a Red Sox hat, a Harvard pen, a copy of my Guantanamo book, and a short research prospectus), I introduced myself. Invariably, I was met with looks of astonishment, and more or less shown the door. That didn’t dissuade me. I said to my taxi driver, Gilberto, “Same place, same time tomorrow.” I didn’t quit until, after three or four visits later, I was granted audiences with the director (“So long as you promise never to come back,” I’d hear).

Meeting the directors of Cuba’s leading research institutions did not guarantee me access to the Castro archives. The breakthrough came in January 2014 when the director of the Office of Cultural Patrimony allowed me to visit the young Castro’s haunts in what was once Oriente Province: where he grew up, went to school, and, later, returned to launch the revolution. On a 10-day tour of the east, what began as frustrating and fiercely curated visits by “official” historians became freewheeling interviews of people who knew Castro as young kids or in the revolution, but who had never been interviewed before. One was an 89-year-old peasant from Castro’s hometown of Biran, who played and went to school with the Castro boys. Over the course of those 10 days, I got to meet and interview some two dozen people throughout the east. We went to the beach town Playa Las Coloradas, where Castro landed in December 1956, to the guerrilla’s command post in the Sierra Maestra. I got to sit on Castro’s bed.

“In my mind, the biggest accomplishment of this book was the trust-building it entailed and the spirit of collaboration, reciprocity, and respect — things that the United States has rarely granted Cuba, in their mind.”

The success of this trip led to me being admitted to the Office of Historical Affairs. Gradually, the woman in charge of the archive began to trust me and started bringing me evidence I hadn’t asked for — always a good sign. In my mind, the biggest accomplishment of this book was the trust-building it entailed and the spirit of collaboration, reciprocity, and respect — things that the United States has rarely granted Cuba, in their mind. On a recent visit, the spirit of collegiality and respect was palpable. I have the hope — this may be an illusion — that the book will contribute to the rapprochement in some way.

I also met Castro’s sisters. Juanita, who is in Miami, made it clear that our meetings were not interviews, but conversations, strictly off the record. Emma, who lives in Mexico City, was much more forthcoming. We spent two long days talking about the family, life in Biran, what she thought of the revolution. She was close to her brother and went back to Cuba a lot. I met some great sources by chance, like Antonio del Conde (el Cuate), the Mexican gun-shop owner who helped provide weapons and training to Castro’s rebels, and later the Granma, [the boat] on which Castro and his rebels returned to Cuba.

GAZETTE: Castro’s love affair with Naty Revuelta was made for the movies. What was she like, and where do those love letters live?

HANSEN: Castro’s epistolary love affair with Revuelta began in autumn 1953. He had met Naty the year before. He was a rabble rouser; she was looking for someone to believe in. Both were married, and they managed their relationship appropriately, at first, though they soon fell in love over letters while he was in jail. There were more than 100 letters between them. Inevitably, the letters crossed one day, as the one meant for Naty went to Fidel’s wife, Mirta Diaz-Balart, and vice-versa. There was a big explosion. Months later, there was a still bigger explosion when Castro discovered that Mirta had a paid position in the Batista government. Castro considered [Fulgencio] Batista his mortal enemy, and he and Mirta got divorced. He got out of jail on Mother’s Day 1955, and he and Naty had a baby, though their relationship was over by the time of their daughter’s birth.

Naty shared the letters with me in spring 2014. She let me photograph the collection. She trusted me to be discreet, and I like to think that I honored her request. I didn’t make fun of two young lovers confiding in one another. I tried to show how they adored each other, and to be scrupulously fair to them. These and countless other letters and artifacts at the Office of Historical Affairs are illuminating, revealing 20, 30 years of Castro’s early development.

GAZETTE: Who else is in your sights as a good biography subject?

HANSEN: I am not sure. I have different thoughts: Castro’s brother Raul, former California Gov. Jerry Brown. I’ve been going to Rwanda with my wife, Anne, a physician at Boston Children’s Hospital, for the last decade, and I am in conversations with the office of Rwandan President Paul Kagame about a biography of him. If the Castro biography doesn’t get me murdered, a Kagame biography surely will. He is precisely the sort of figure I like to focus on: vilified by the human rights community in the West, praised by people of an entrepreneurial bent. To the outside world, he looks like an autocrat; to the development and medical people, he looks like he has done a lot of good. Whatever you make of him, he has done a remarkable job rebuilding a country 25 years post-genocide with some sort of democracy. Not the kind of democracy we pride ourselves on, but one in which many Rwandans sense that they have a say in what’s going on.

The point would be to suspend Western presuppositions about what a Rwandan government should look like and examine what’s going on there from a Rwandan and African perspective. I’m not sure we Westerners have a monopoly on what is good and what is right for the rest of the world. The terminology we so often employ to describe foreign leaders — a caudillo, an “African strongman” — as often precludes as facilitates thoughtful, critical inquiry. Above all, I don’t like writing books where you know the outcome before you crack the cover.