Courtesy of Harvard University Archives

Striking lessons from the 1960s

Event commemorating student protest that rocked the campus will connect to today’s student-activists

Miles Rapoport ’71 boasts an impressive resumé. He spent 15 years as a community organizer and another 15 as a state legislator and the secretary of state in Connecticut. In 2017, he was appointed a senior practice fellow in American democracy at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation. This year, Rapoport added another title to his resume: event planner.

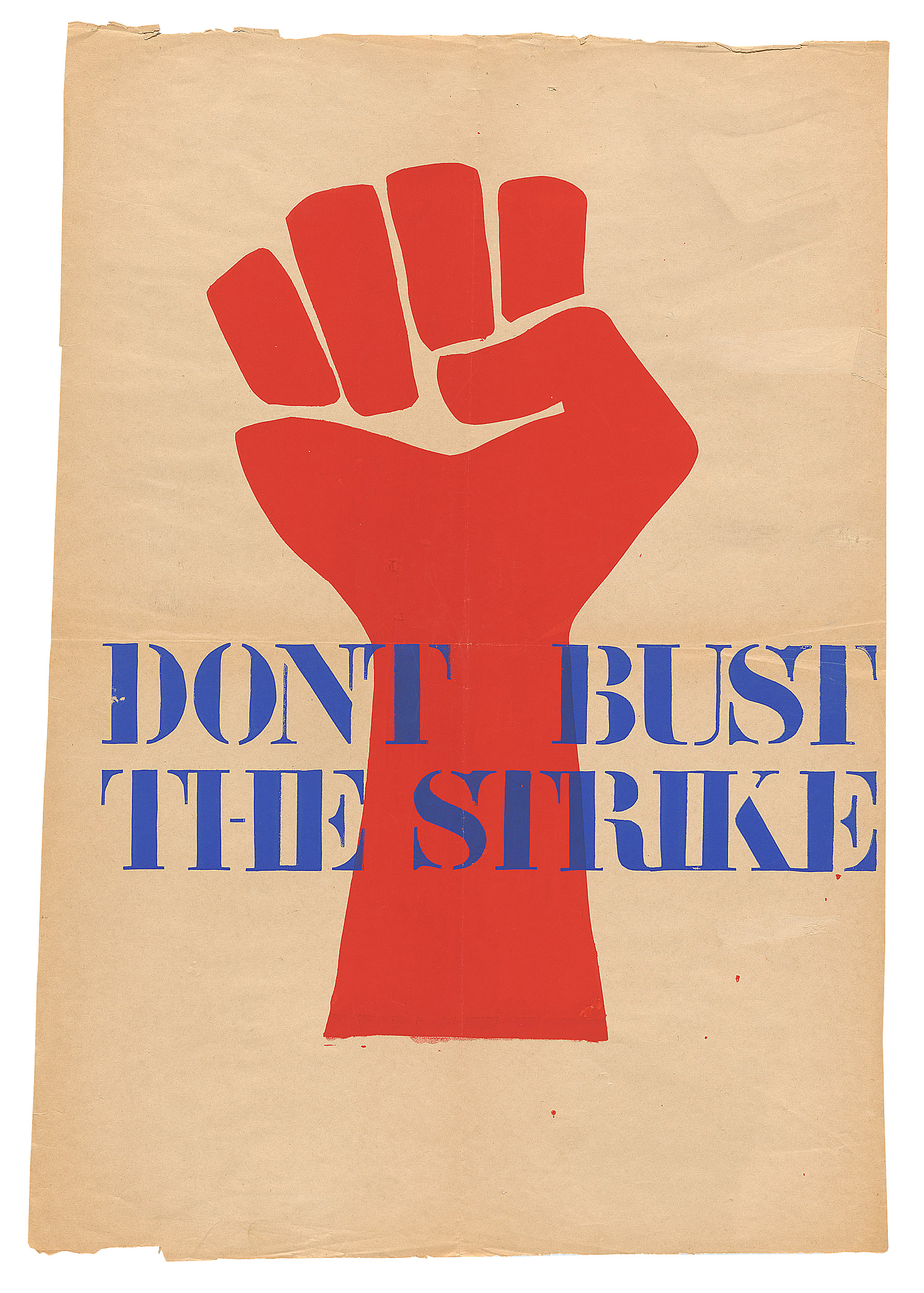

To mark the 50th anniversary this month of the Harvard strike of 1969, Rapoport has organized what he hopes will be a meaningful commemoration of the iconic moment of activism on campus that will engage critical reflection of its successes and failures. In his HKS office — which has a poster from the ’69 strike — Rapoport described the event, which will feature strike participants and current College activists, as “an intergenerational conversation about activism then and now.”

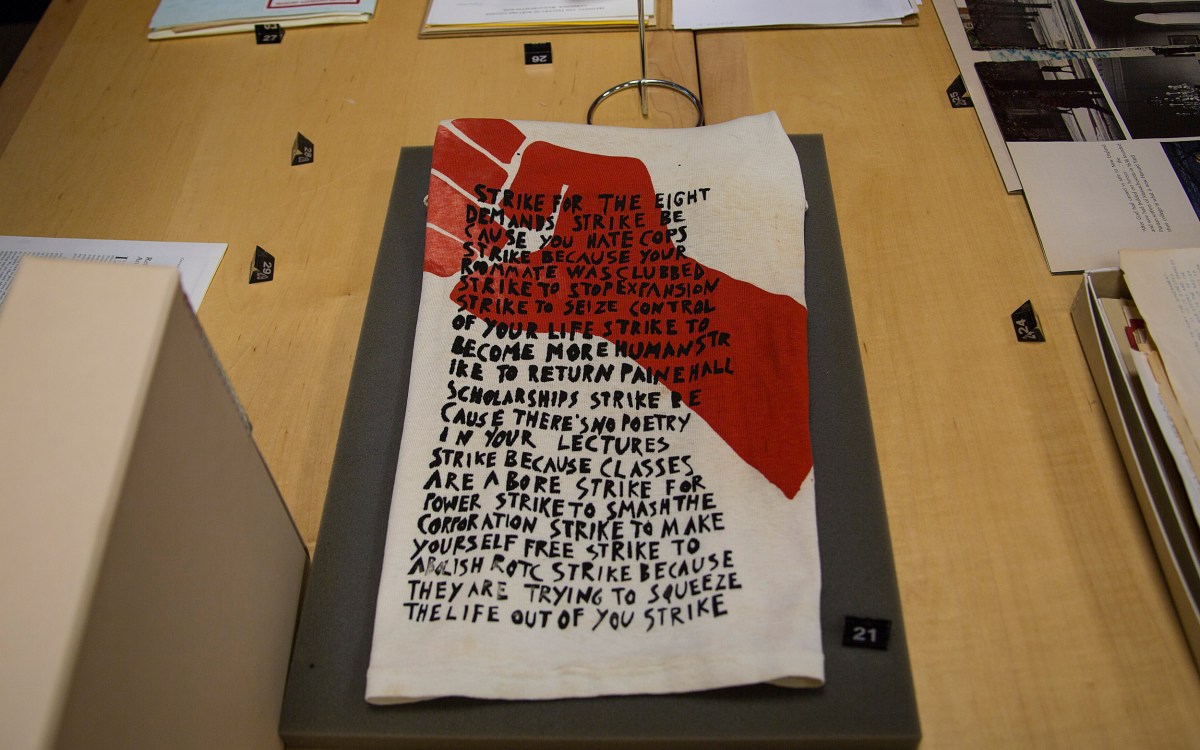

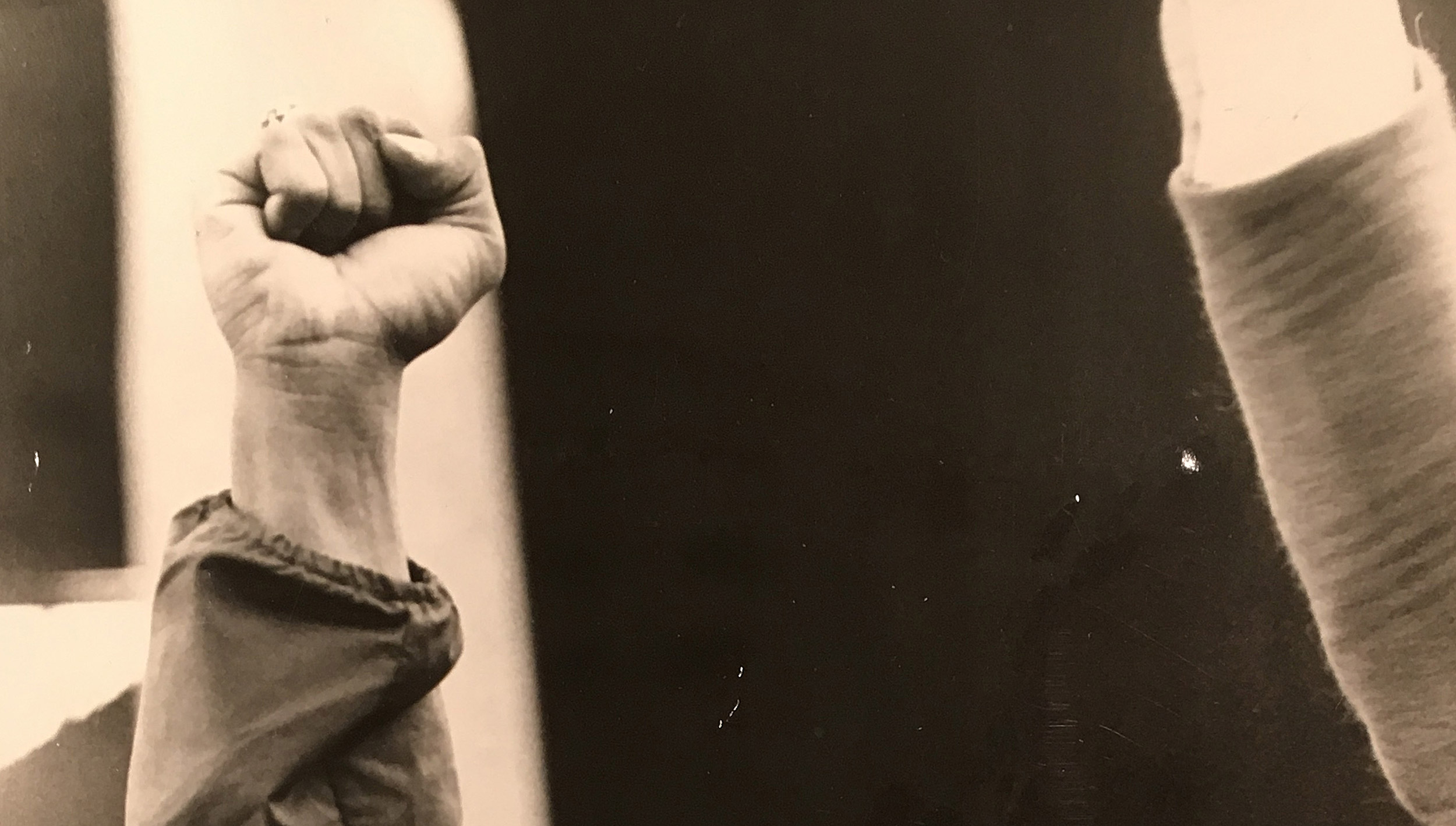

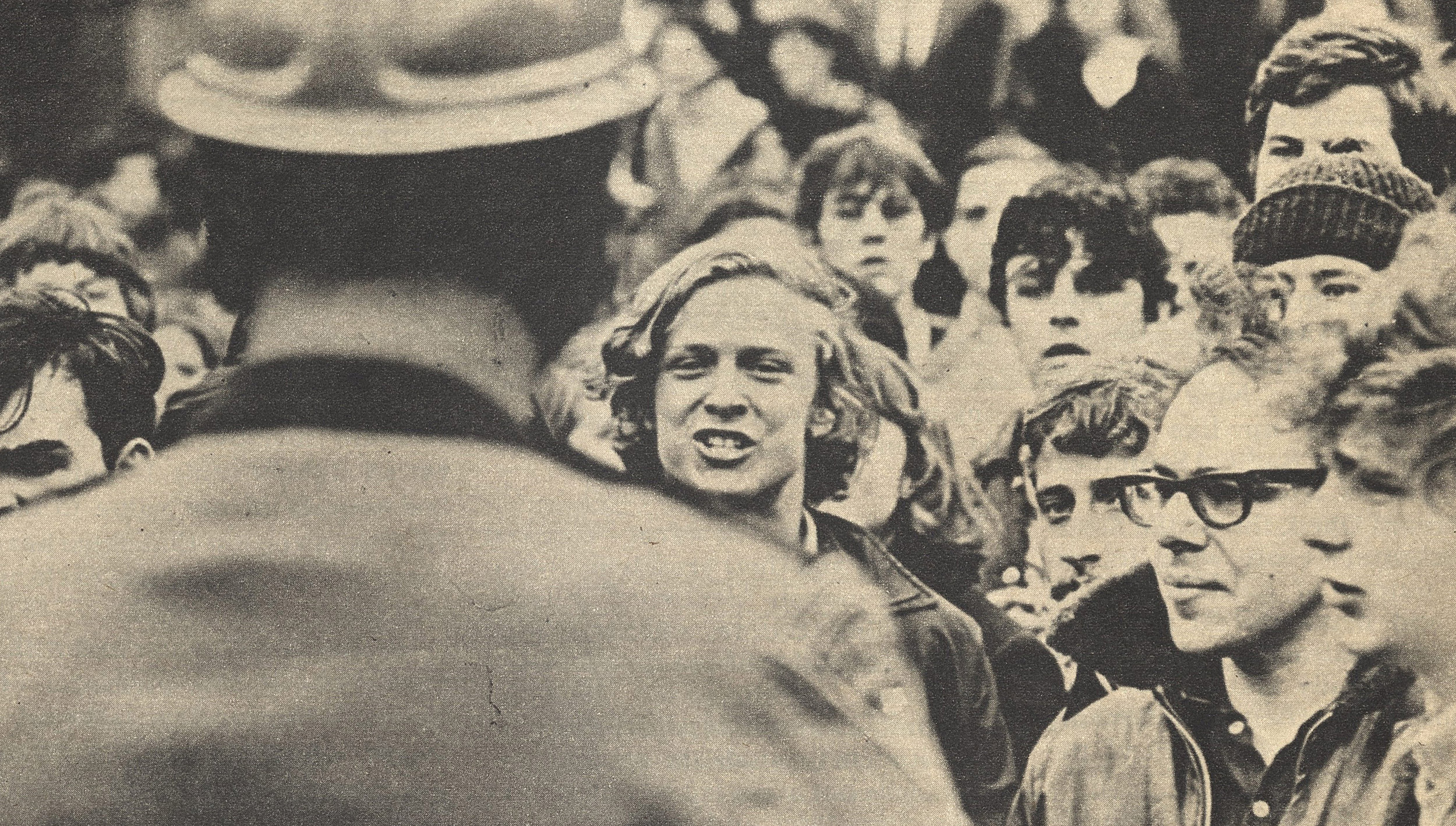

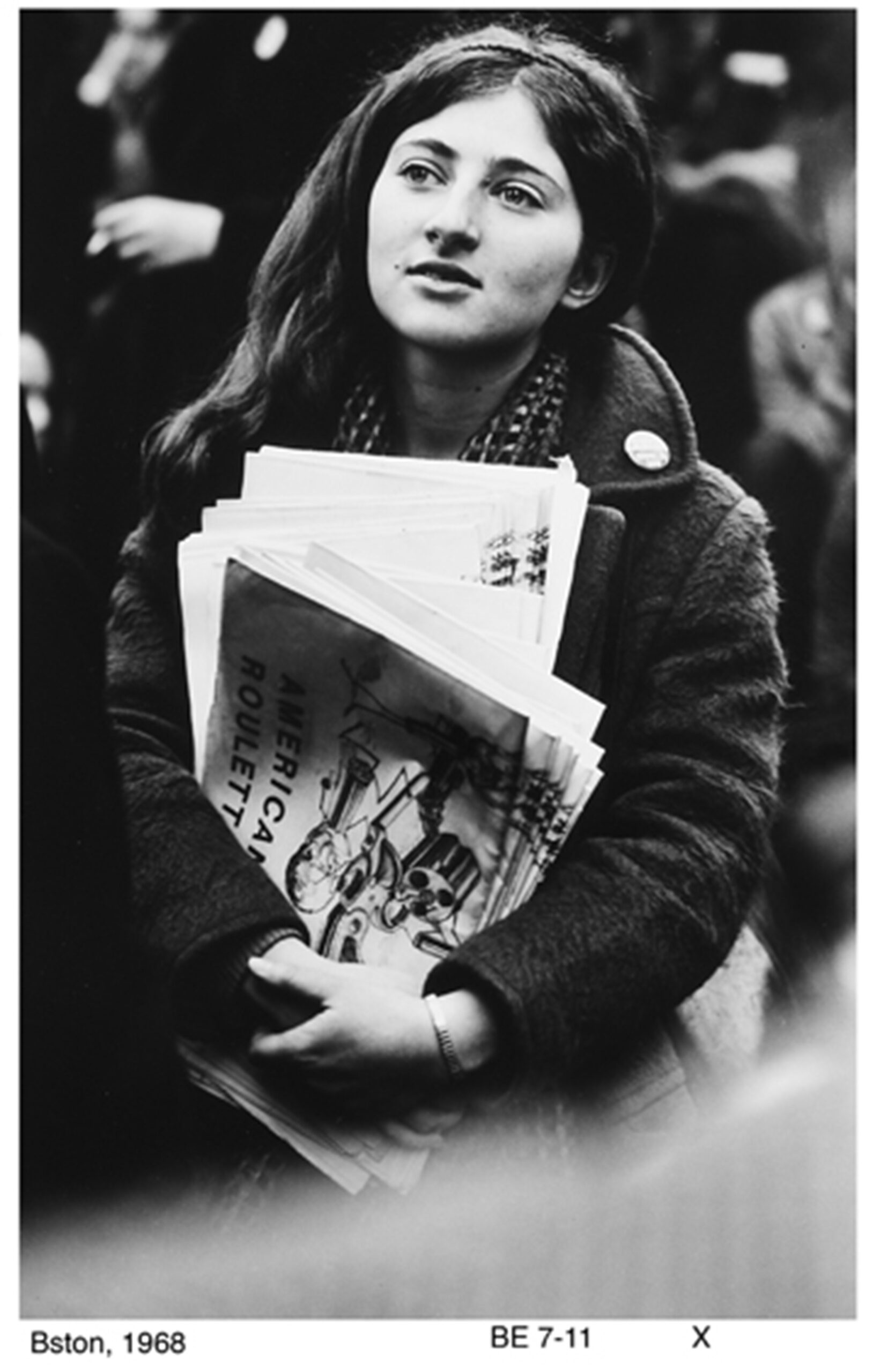

Rapoport was a College sophomore when he and about 500 other student-activists took over University Hall on April 9, 1969, to protest Harvard’s role in the Vietnam War. The students demanded that Harvard end its Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program, which was providing officers for a war they considered morally bankrupt. Harvard President Nathan Pusey called city and state police onto campus to remove the protesters, who had vowed nonviolent resistance, and before sunrise the next day about 400 officers in riot gear used what some accounts called excessive force against the students. According to Harvard a Crimson article published the following day, “between 250 and 300 people were arrested in the raid, and nearly 75 students were injured.”

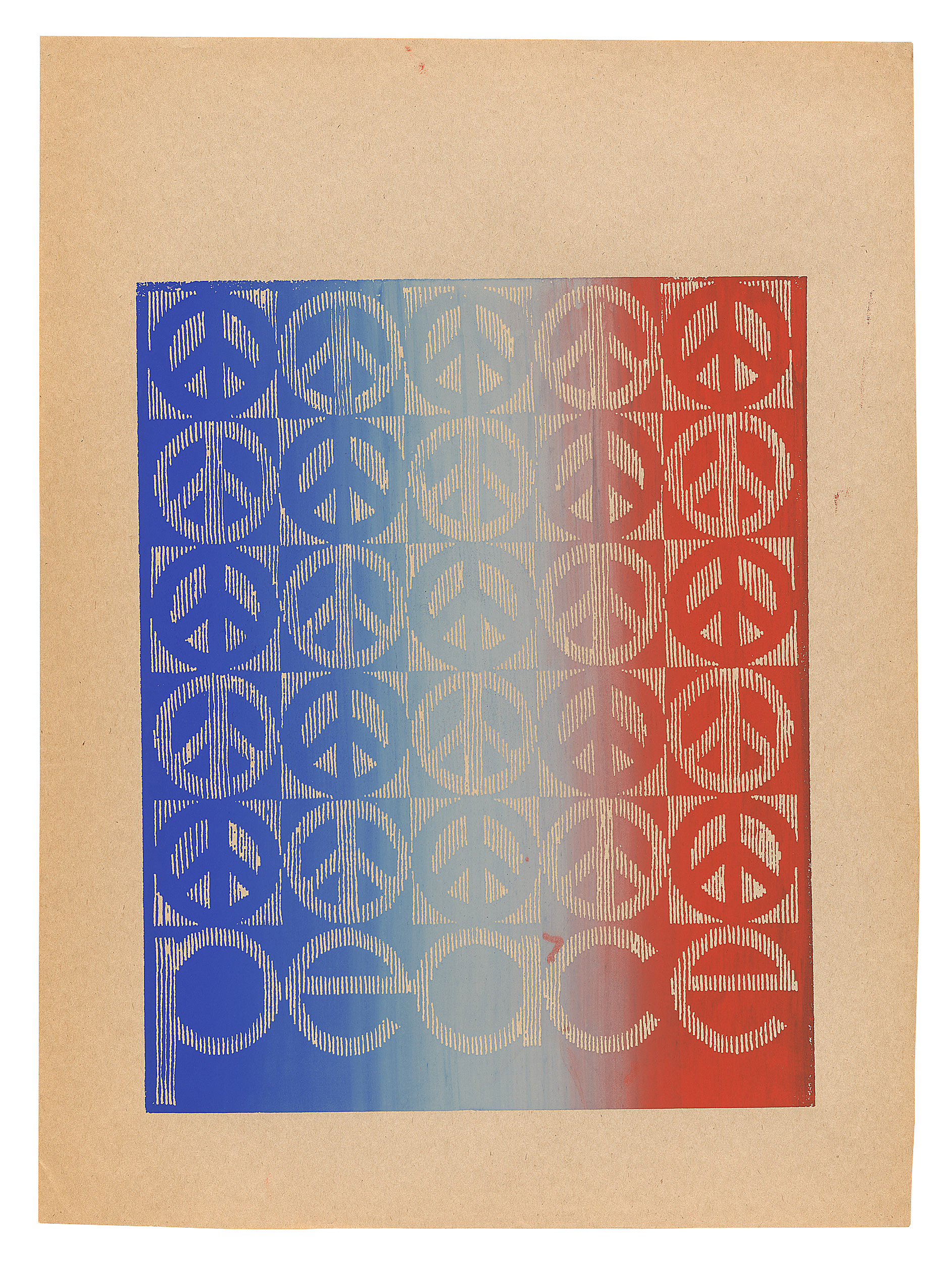

Images courtesy of Harvard University Archives

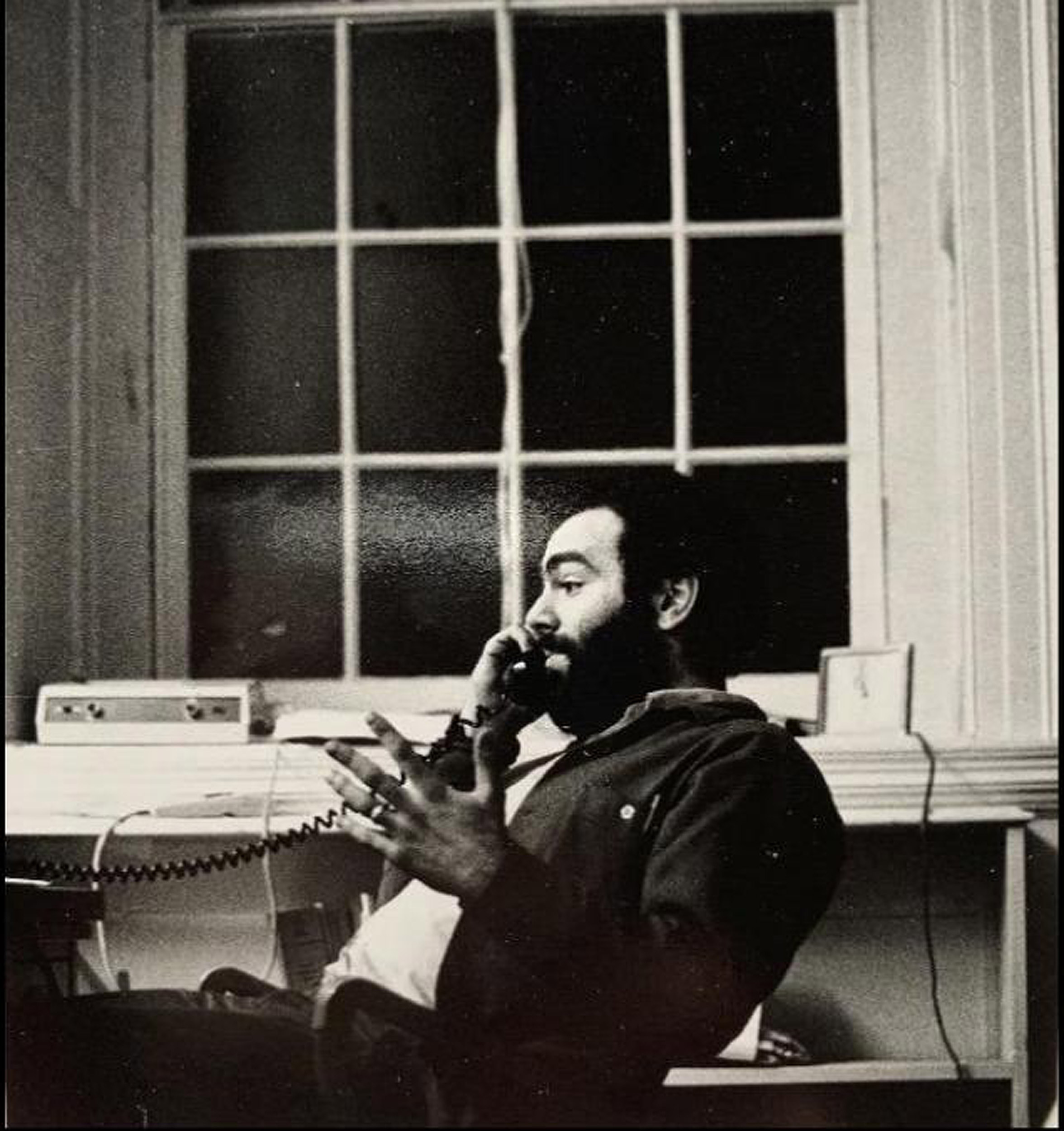

Chris Wallace, then-reporter for WHRB, reports from University Hall on April 9, 1969. Credit: WHRB

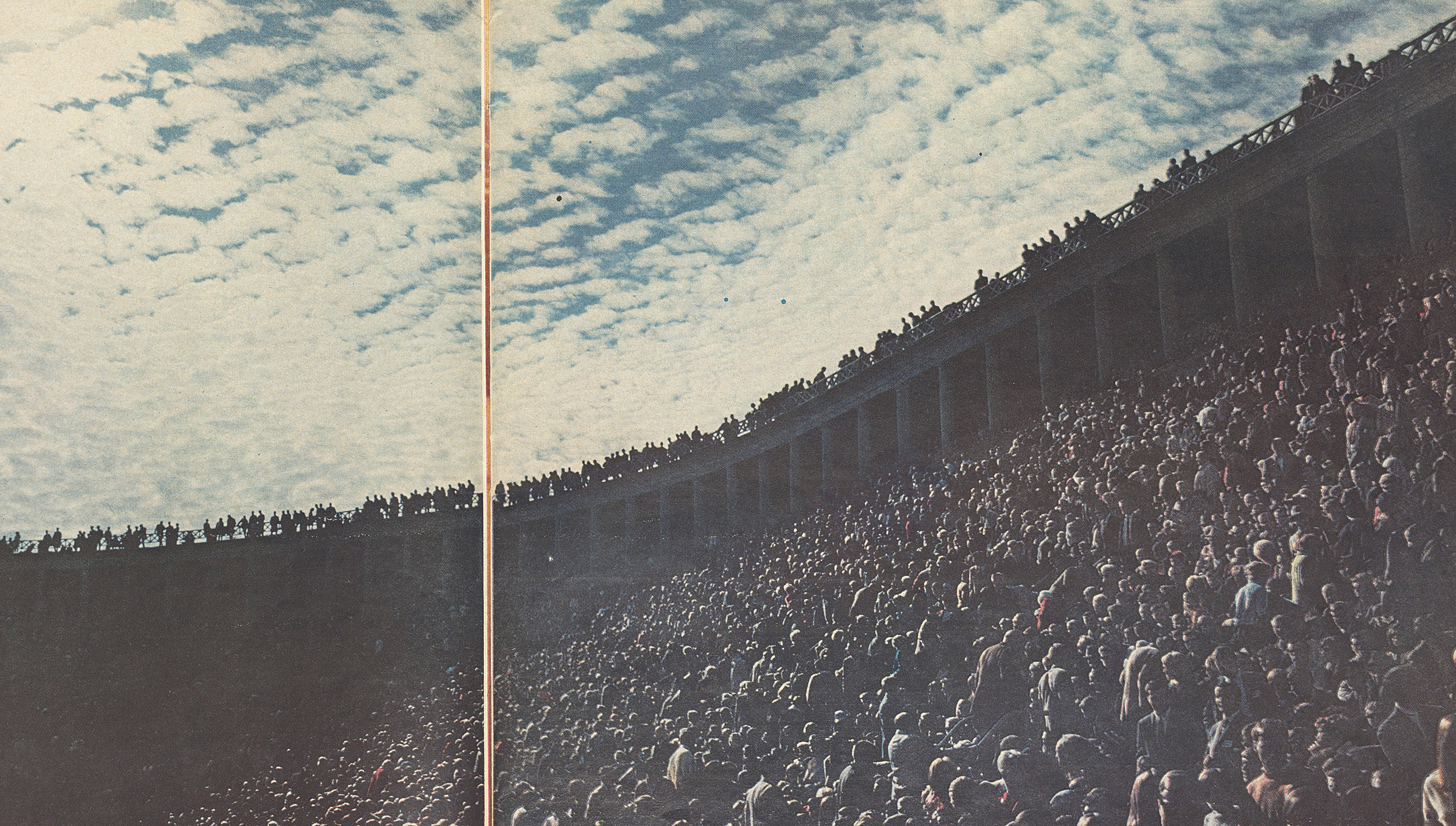

In response, by April 11 thousands of Harvard students, teaching fellows, junior faculty, and a few senior faculty from all parts of the University had gathered in Harvard Stadium, striking and boycotting classes.

The occupation wasn’t a step taken lightly. “There was a lot of time spent in conversation about the war in dining halls and dorm rooms,” said Rapoport, who was one of the students arrested. “There was a lot of time in meetings. There were one-to-one conversations, knocking on the doors in dorms. There were teach-ins. There were debates in various Houses. There were various demonstrations on campus. It was not as if [the events in April] came out of the blue. There was a lot of work that went into it before hand.”

Susan Jhirad ’64, Ph.D. ’72, a lifelong activist and now a retired teacher, was one of two women on the strike steering committee and a graduate teaching fellow in 1969. She was arrested, expelled, and later readmitted to Harvard.

“We accomplished some of the things we set out to do,” she said. “We got rid of the ROTC, at least for a while. We got an African American studies program [now the Department of African and African American Studies]. Harvard built low-income housing on Mission Hill. We won some of our basic demands. We actually effected social change. It’s important for young people to know that change is possible.”

“We actually effected social change. It’s important for young people to know that change is possible.”

Susan Jhirad ’64, Ph.D. ’72

Hugh Calkins reads Corporation statement on April 18, 1969, responding to students’ eight demands. Credit: WHRB

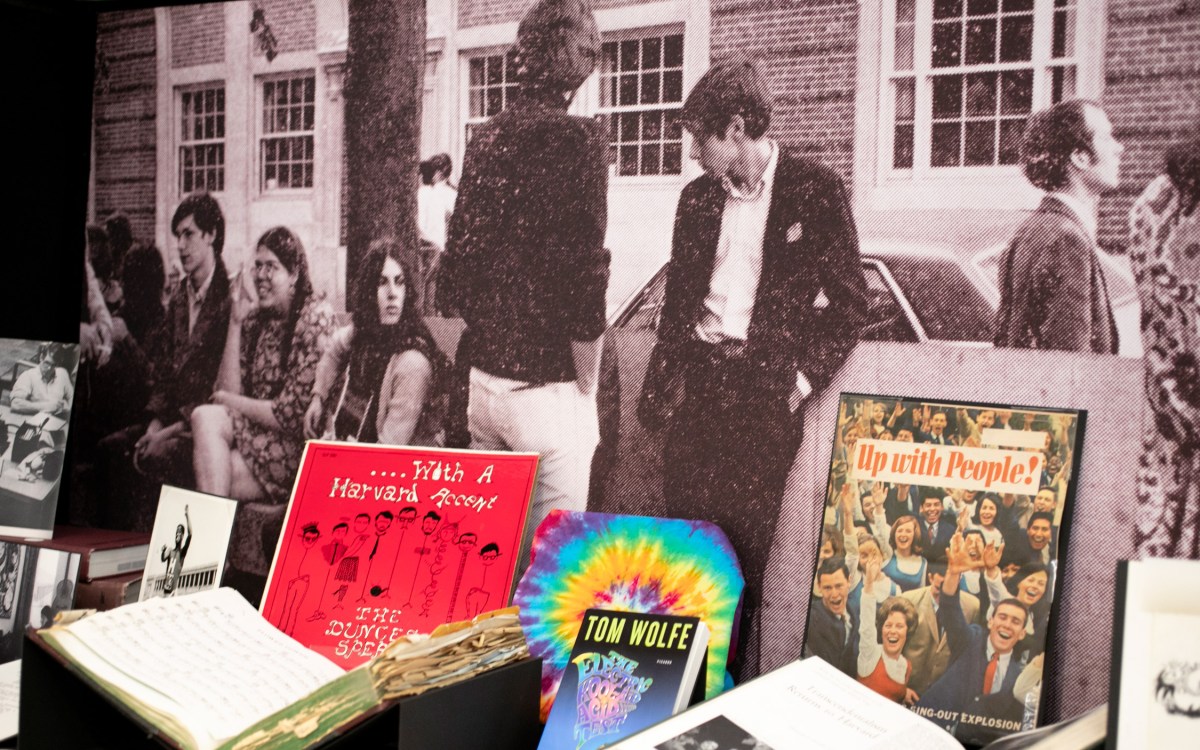

On Friday, a daylong event called “The Strike of 1969, Protest at Harvard, and Organizing Today,” will feature conversation between strike participants and current student activists moderated by Jhirad, a 90-minute session devoted to small intergenerational discussion groups, and an evening reception in the Nathan Pusey Library, where the current exhibit features archival materials from the student uprising. About 100 strike participants are expected to attend.

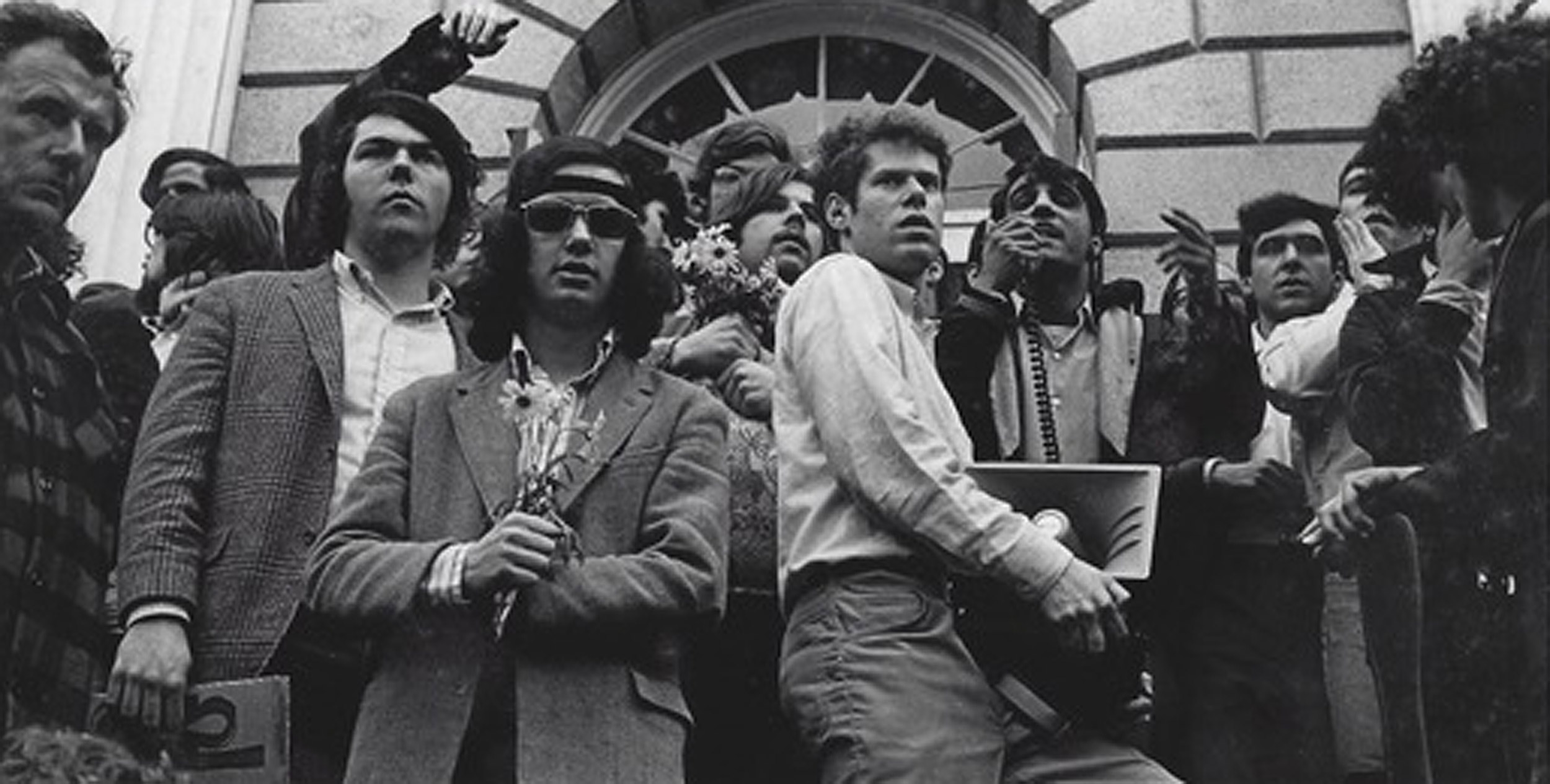

A sampling of Friday’s panelists, today and in the ’60s: Michael Ansara (above), a longtime organizer and co-founder of Mass Poetry. Below, Judy Lieberman is now a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and Nate Goldshlag, a retired engineer.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer; Antonia Forster

Photos courtesy of Judy Lieberman

“Young people today seem so much smarter than we were. They balance the need for protest with the need for elections.”

Michael Ansara ’68

In the archival image, Goldshlag is holding the bullhorn.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer; courtesy of Nate Goldshlag

“The events of 1969 were a watershed moment in the antiwar movement,” said Rapoport. “They were a major marking point for the University, and they were a life-changing experience for the people who were part of them. Fifty years later it seems important to mark that moment and engage in discussions with activists on campus today who are dealing with this generation’s version of the critical issues of our time.”

Michael Ansara ’68, a longtime organizer who co-founded Mass Poetry, a Boston nonprofit that seeks to bring verse to a larger audience, returned to Harvard a year after graduating to help coordinate the occupation and the strike, and was among those arrested. He wants to demystify the ’60s and hopes the intergenerational conversation will be as much a reflection of the more mundane work of organizing and persuasion as a reminiscence of the dramatic moments of the strike.

“Student activists have the history of ’60s radicalism to compare themselves to, for better or for worse,” he said. “There’s a mythologizing about the decade that doesn’t help today’s student-activists.”

What is often overlooked, Ansara said, is the years of work student activists put into protesting against the war. Isa Flores-Jones ’19, who will be a panelist on Friday, has similar feelings about the legacy of 1969.

“It’s inspiring to think of a time when students showed up to support campus activism en masse, but it’s also possible to misconstrue the activism of the ’60s and forget that there were a lot of dissenting opinions across movements,” said Flores-Jones, the coordinator of Divest Harvard. “Movement work takes a huge amount of collaboration and coordination. There’s no single-issue movement, just like there’s no single-issue person.”

Flores-Jones, like Rapoport and other members of the 1969 strike, spends many hours focused on the nitty-gritty of organizing. “Day to day I answer a lot of emails and attend a lot of meetings,” she said. “Also, I do a lot of thinking about how to make other peoples’ work easier; how to delegate responsibility and make people feel comfortable working with one another.”

In reflecting on their successes and failures Friday, members of the ’69 strike who are participating in the anniversary will help current student activists like Flores-Jones figure out how to create structural change and perhaps even a sustained shift in power. In doing so, they hope to build institutional memory among generations of Harvard student activists.

Images courtesy of Harvard University Archive

The biggest lesson they’d like to impart? Vote.

“We didn’t vote,” said Jhirad. “We thought both parties were involved in pursuing the terrible Vietnam War so it was hard to vote for any of them, and then Richard Nixon got elected.”

Ansara recalled that a popular chant among activists at the time was, “Vote with your feet, vote in the streets!”

“Young people today seem so much smarter than we were,” Ansara added. “They balance the need for protest with the need for elections.”

Despite their mistakes, members of the ’69 strike had many successes, realizing much of the change they set out to create. “It’s a reminder that students do have power and can effect change on campus,” said Arielle Blacklow ’21, co-president of Harvard Undergraduates for Environmental Justice. “I hold that close.”

“In 1969 the overarching issue was the war in Vietnam, and stopping that felt like an urgent moral imperative for students at the time,” Rapoport said. “Today’s equivalent is climate change. Every scientific report gets worse and worse in terms of the danger and the speed at which current policies are endangering the planet and the children, so I think students of today are feeling that same urgency. A major impact the strike and organizing had back then is I think it gave students a sense that they could make a difference. Their voices can be heard. They need to be emphatic, but change is possible.”

On the 50th anniversary of the student takeover of University Hall, George Abbott White (center), today a teacher and writer in Boston, speaks to a gathering of activists past and present.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Flores-Jones said she has been incredibly inspired by the work of the ’69 strikers. “We’d love for any members [of the strike] to add their voices to our call for action against fossil fuels and the prison-industrial complex,” she said, “Many of them already have.”

Rapoport, for his part, said he learns as much from students like Blacklow and Flores-Jones as they do from him.

“Young people today have such a sophistication about strategy, tactics, and communication,” he said. “Activists today are leveraging power as consumers, and voters, and that’s borne some real fruit. We want to share our experiences, and we want to absorb energy and ideas of the students as well.”