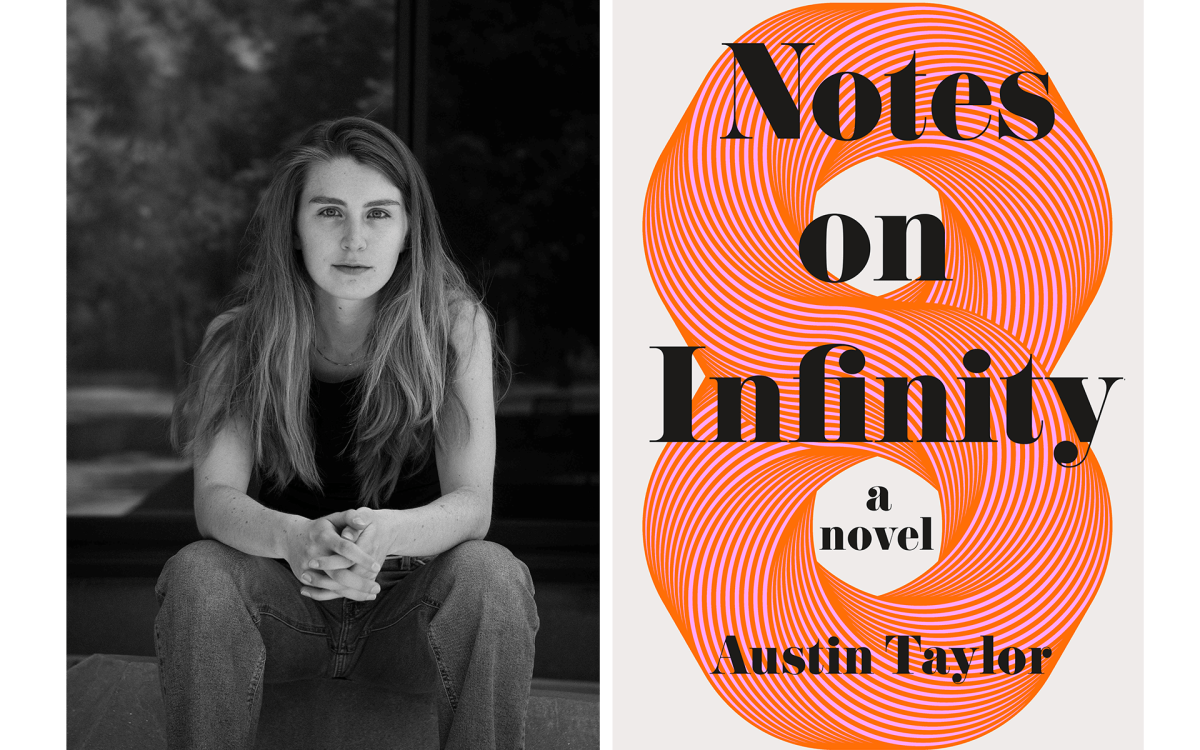

Radcliffe Fellow Francisco Goldman is writing his latest novel based in New Bedford.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Fishing for stories

Francisco Goldman explores New Bedford for his latest novel

In 2005, author and journalist Francisco Goldman had the idea to write a novel set in New Bedford, Massachusetts, a place he sees as a quintessential immigrant city, with its influx of Central American migrants. Then, in 2007, tragedy struck.

Goldman’s wife, the writer Aura Estrada, died in a body-surfing accident while the pair were vacationing in Mexico. The loss sent Goldman’s writing on an unforeseen autobiographical path as he dealt with his grief. Now, 12 years later and after having released his highly praised novel based on her death — “Say Her Name” — Goldman is returning to his idea of a New Bedford novel as a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, where has also been finishing his forthcoming book, “Monkey Boy.”

Goldman’s stories often revolve around Central America, whether they’re fiction, nonfiction, or articles for magazines like Esquire, Harper’s, or The New Yorker. He spent much of the 1980s covering the region’s many wars and more recently has written about the abuse and corruption that led to a fire in Guatemala that killed 40 teenage girls and a series on the 2014 kidnapping of 43 students in Iguala, Mexico.

The Gazette spoke with Goldman in advance of an event on Tuesday where he will talk about the new novel and New Bedford. Goldman — the author of four novels, two nonfiction books, and numerous articles — reflected on his current research and what pulls him to Central America and New Bedford.

Q&A

Francisco Goldman

GAZETTE: A lot of your work as an author and journalist focuses on Central America, its people, and its migrants. Why is it that you are drawn there?

GOLDMAN: It’s my family place. It’s not just that my mother is from Guatemala — I spent a lot of my early childhood there. I guess I would have grown up there if I hadn’t gotten sick. [Goldman had tuberculosis as a child.] That’s why we came back to here. I needed to be able to go to the hospital in Boston and we stayed. But there was always a sense of Guatemala being the place where I felt I was from. My mother really inculcated that in us.

GAZETTE: How did you start covering Central America?

GOLDMAN: After leaving the University of Michigan, I came to New York and was working as a waiter while trying to write. But it’s very hard to make time to write when you’re a young person in New York, having to work restaurant jobs like five days a week — more, even. Finally, I thought that I should apply to an M.F.A. program. Then, to make the time to write, I decided to go down to my uncle’s house in Guatemala — actually to a family cottage on a small lake outside the city. I’d thought I’d hole up there and write.

“I got [to Guatemala] and my uncle said, ‘You can’t go out there! The guerrillas just hit the police station out there.’ It was like full-scale war there.”

Francisco Goldman

I got there and I was so naive. Whatever my heritage, I was still basically a suburban Massachusetts kid. I got there and my uncle said, “You can’t go out there! The guerrillas just hit the police station out there.” It was like full-scale war there. This was in 1979, during the civil war. That was the most violent year in the history of Guatemala City, though the subsequent three or four years would become the most violent in the country.

It was nightmarish and I was there living in my uncle’s house trying to write these stories that were essentially New York City love stories. I thought, What is going on here? But you couldn’t get any information; the local media couldn’t report anything, so it was like living in a fog.

Then I got very lucky because I got into various M.F.A. programs and Esquire magazine bought two of my stories I had sent them. After these stories were published, Esquire offered me the chance to do a nonfiction piece. So, at this point I was choosing between doing this one piece that pays $1,000 — which to me was a lot of money, ha — versus a full scholarship to get my M.F.A. I took the Esquire piece because I wanted to go back to Guatemala and write a piece about what was going on there. And that’s how it started.

GAZETTE: Your newest novel, which you are working on at the Radcliffe Institute, is set in New Bedford. Why there?

GOLDMAN: Well, first, it really just hit a chord — New England held so many literary resonances for me. “Moby Dick” is probably my favorite novel; Hawthorne in the Customs House in Salem, and the Lovecraft coast [author H.P. Lovecraft set many horror stories in fictional Massachusetts coastal towns]. So when I found out that it had also become the center of a Guatemalan and Maya immigrant community — many of whom essentially migrated here in the ’80s during the war — that just spoke to me so deeply. I just had to get to know it.

GAZETTE: What were some of your impressions?

GOLDMAN: On visiting New Bedford, I had this feeling of almost being in kind of a New England border town. Some of the elements that you associate with a Texas border town you’ll find in New Bedford, that sense of a place where people are crossing over to the U.S., goods but contraband, too, people from all over, a sense of danger, too. The fish-processing plans are something like maquiladoras [factories in Mexico run by foreign countries]. And of course, the omnipresent menace that is ICE. It’s like a New England border town.

Author Francisco Goldman is exploring a departure from his previous works in his new novel.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

GAZETTE: Why is that?

GOLDMAN: Its history as the site of layers and layers of immigration. Classically, in the past, fishermen’s migrations — Irish, Scandinavian, and Italian; Portuguese is the big 20th-century one; then, communities related to the Portuguese in certain ways have come — Brazilians, Cape Verdeans, Dominicans, and Puerto Ricans. And now, there is this Central American migration, especially from indigenous Guatemala, many among them who had never even seen the ocean when they were in Guatemala.

GAZETTE: What can you tell us about this new novel? What’s it about?

GOLDMAN: I don’t know yet. I have some ideas, but prefer to keep them to myself at this point. Though I’ve been dropping in on New Bedford for years, I’ve just started to research it for a novel. I’m just sort of watching different images and ideas float around in my head as I research. What I do know is that I’m tired of working in the first-person voice, having done that now for three straight books. I really want something much more polyphonic now. I do know a few characters are going to carry over from the novel I’ve just finished, which does in fact end in New Bedford.

GAZETTE: How does research influence your story?

GOLDMAN: The research sends you down surprising trails. You find incredible stories, but you have to be very careful you don’t go down too many. Right now, the more I learn about the history of New Bedford — like old Quaker shipping families, their involvement with the Underground Railroad, the role that Quaker ship captains played in helping slaves escape — I feel so tempted to try to figure out how I can do something with that, though I vowed not to write a historical novel. But the past so resonates with the present, the sanctuary movement, and so on.

The novel I’m finishing now [“Monkey Boy”] was 800 pages long when I got here in September. Right now, it’s about 310, so you write a lot of stuff and use a lot of research that you end up throwing out. Believe it or not, that’s one of the fun parts.

GAZETTE: What other trail has your research set you on for the New Bedford novel?

GOLDMAN: I’ve been fascinated by the commercial fishing industry, the fishing fleet, and especially the fish processing houses where so many of the Guatemalans are employed. When Guatemalans come to the U.S., they mostly follow their communities. You could lay a map of Guatemala over the states, especially over New England, and it’d be a really funny version of Guatemala, because it’d be all the same towns but they’d all be in different locations. The New Bedford Guatemalan community, for example, mainly comes from a group of neighboring towns in El Quiché, which was the department hardest hit during the Guatemalan military’s scorched-earth campaigns during the war. In 1981 the town of Zacualpa had a population of 18,000 but by 1983 only two families were living there — the rest had either been killed or fled. In a New Bedford fish processing plant, I saw a trophy case in the lobby, they’d just won the fish processing league’s soccer tournament, or whatever, and I saw that their team was called Zacualpa United. There’s a lot of trauma in New Bedford’s Guatemalan community, of course, but also a lot of determination and resilience and organizing and resistance. I’ve even found a couple of young Guatemalans who are now working on fishing boats, and in New Bedford that is the iconic workingman’s profession. The fishing fleet has a special stature there, and you think of the generations and generations of boys who’ve gone to sea, from one immigrant group after another, and now, well, that there are Mayas and other Central Americans getting a toehold there, that just seems so a piece with New Bedford’s history.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.