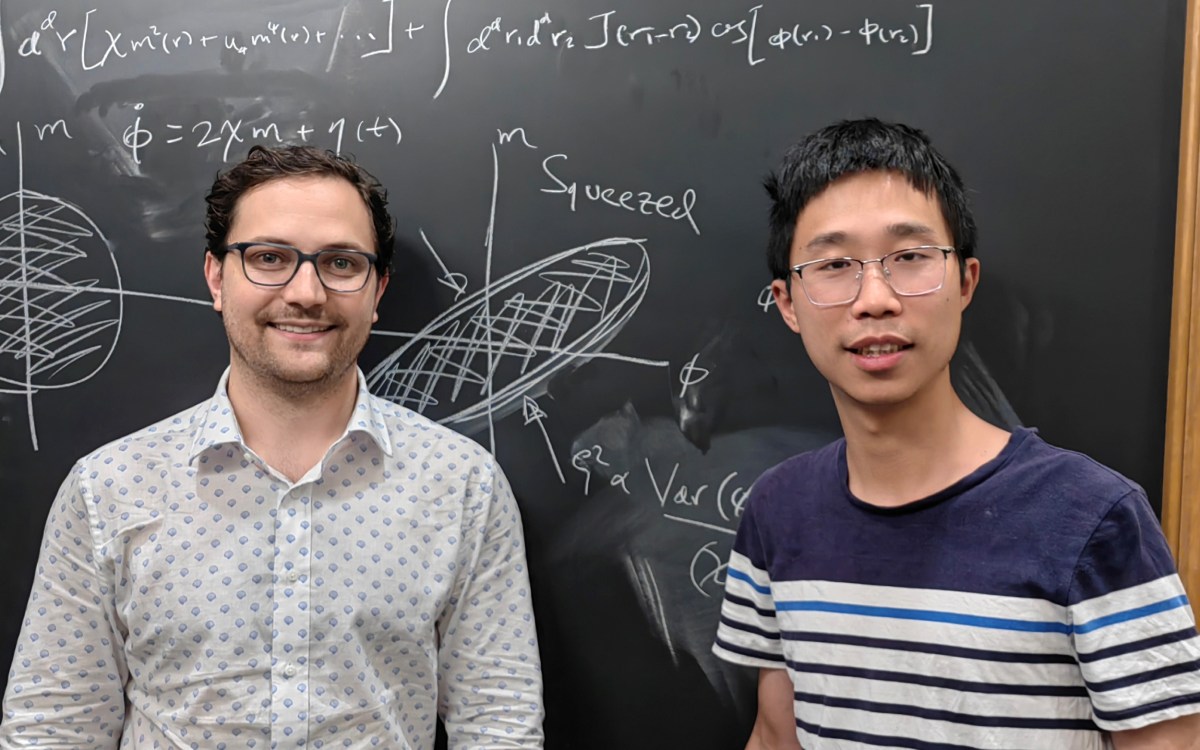

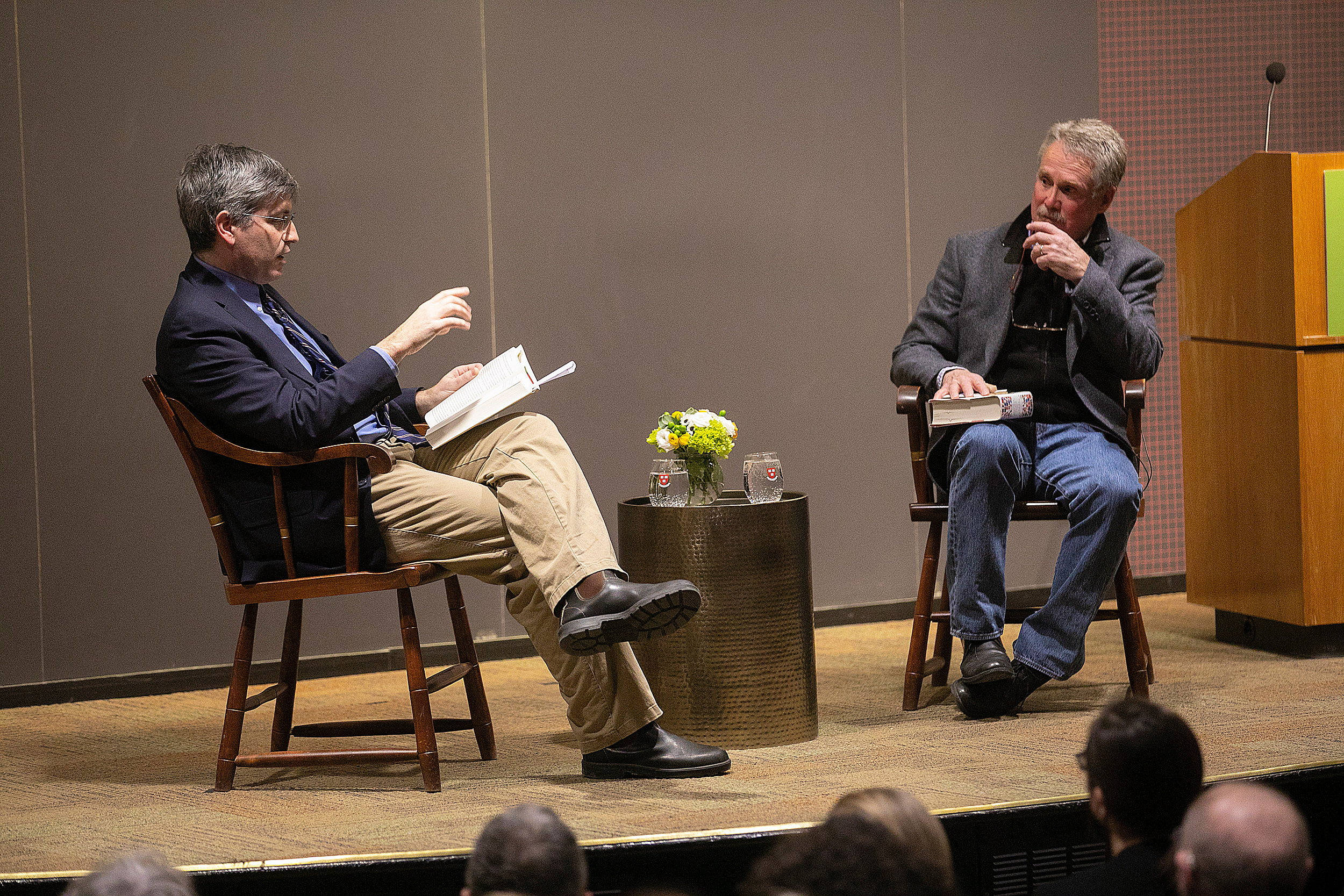

Science writers Carl Zimmer (left) and David Quammen discuss their new books on evolution.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Mining the mysteries of DNA

David Quammen and Carl Zimmer discuss how tangled the tree of life can be

Writing about science is often about finding the unexpected in the routine, as in sequencing numbers or molecules. Yet as author and journalist David Quammen and science writer and columnist Carl Zimmer know, writing about science can also be an art.

In a conversation at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, the two writers discussed the craft behind their art, as well as the stories that led them to their new books — “The Tangled Tree” and “She Has Her Mother’s Laugh,” respectively — both of which focus on genetics and recent developments in our understanding of DNA. (The event also celebrated the 10th anniversary of the “Evolution Matters” speaker series, which is now endowed through a major gift from longtime supporters Herman and Joan Suit that was announced Thursday.)

Quammen began Thursday evening’s session by explaining that genetics is far from the linear, logical field we may have been led to believe by our high school biology teachers. Our DNA, he said, does not merely come down to us from our parents, but can also arrive “sideways,” from invasive elements like viruses or even from our siblings and progeny.

Noting the groundbreaking work of University of Illinois professor Carl Woese, “the most important biologist of the 20th century that you’ve never heard of,” Quammen talked about horizontal gene transfer, explaining that roughly 8 percent of what people now recognize as human DNA came to them sideways by being adapted from viral invasions.

“What Woese found out,” explained Quammen, “is that the ‘tree of life’ isn’t tree-shaped. When we talk about a tree, one of the most basic things is that it starts with a trunk. It’s all about divergence. What Woese found out was that there was also convergence” — that is, that it can create similar structures that were not present in the last common ancestor of the two groups being compared — which is supposed to be impossible.”

Such apparent contradictions, said Quammen, were irresistible to him as a journalist. “I went down the rabbit hole,” he said. “It turns out [convergence] is possible, it is real, and it is very counterintuitive.”

Like Quammen’s, Zimmer’s latest work explores the unusual and often counterintuitive paths genetics can take, from horizontal gene transfer through the equally unexpected genetics of human chimeras, in whom DNA has absorbed and replicated material from others, notably fetuses or siblings in utero.

“I decided to write a book about heredity,” said Zimmer, who is also a podcaster and a New York Times columnist. “And I was determined to tell stories that people would enjoy reading because they haven’t read them a million times since eighth grade.”

“She Has Her Mother’s Laugh,” which was named a Times notable book for 2018, ranges from the work of such pioneering scientists as Dutch botanist Hugo de Vries, who essentially rediscovered Mendelian genetics, to the current science of CRISPR gene editing.

What Zimmer found was that, contrary to popular thought, our DNA is not set at conception. “The fact is that for all of us,” he explained, “as soon as the fertilized egg starts dividing, the DNA starts mutating. So a cell in your eye and a cell in your big toe probably have different mutations because they have different histories of development.”

Nor, he stressed, is DNA implicitly distinctive. “There is nothing individual about you,” he maintained. “You’re a composite; all of us are mosaics. Individuality is way overrated. Even what a species is is way overrated.”

What makes a science writer may also be a question more of mutation and chance than genetics. As both authors acknowledged, neither began as a science writer.

Quammen described himself as “obsessed with William Faulkner.” But after limited early success as a novelist, he found himself doing other work, often menial, and then, ultimately, journalism. “I gradually discovered that I really loved nonfiction about science,” he said. “I discovered nonfiction could be an artful branch of writing.”

For Zimmer, the path was a little more direct. Growing up, he read Stephen Jay Gould and Isaac Asimov, but “I never said, ‘I’m going to be a science writer,’” he recalled. “I [just] knew I wanted to be a writer.” The decisive factor? An early job as an assistant copy editor at Discover magazine: “That was it,” he said.