Ashley Nunes, a fellow at Harvard Law School, speaks during The Harvard Global Health Institute conference on AI in health care.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The algorithm will see you now

Symposium examines promise, hype of artificial intelligence in health care

In 2016, a Google team announced it had used artificial intelligence to diagnose diabetic retinopathy — one of the fastest-growing causes of blindness — as well as trained eye doctors could.

In December 2018, Microsoft and the pharmaceutical giant Novartis announced a partnership to develop an AI-powered digital health tool to be deployed against one of humanity’s oldest scourges — leprosy, which still afflicts 200,000 new patients annually.

Around the world, artificial intelligence is being touted as the next big thing in health care, and a potential game-changer for billions living in regions where medical infrastructure is inadequate and doctors and nurses scarce.

Despite that potential, some fear that too-rosy views of AI’s promise will lead to disappointment and, worse, rob scarce health care dollars from desperately needed investments in existing medical infrastructure. Experts in AI and global health gathered at Harvard this week to survey the complex artificial intelligence-global health landscape, examine what’s being done today and what’s promised for tomorrow, and try to separate reality from fantasy when it comes to AI’s potential impact on global health.

“The promise of AI is enormous, but the challenges are often glossed over,” said Ashish Jha, faculty director of Harvard Global Health Institute (HGHI). “We have this sense that they’ll somehow take care of themselves. And we know they will not.”

About 50 experts in the use of artificial intelligence and other digital health care technologies gathered at Loeb House for an all-day symposium on “Hype vs. Reality: The Role of AI in Global Health,” sponsored by HGHI. It featured talks by representatives from academia, health care, and industry, including Google AI and the pharmaceutical giant Novartis. Principals also spoke for startups Aindra Systems, which uses AI to rapidly analyze pap smears for evidence of cervical cancer, and Ubenwa, which has developed an AI-based system to analyze infant cries to detect birth asphyxia, a leading killer of children under 5 that’s traditionally diagnosed through time-consuming blood tests and lab analyses.

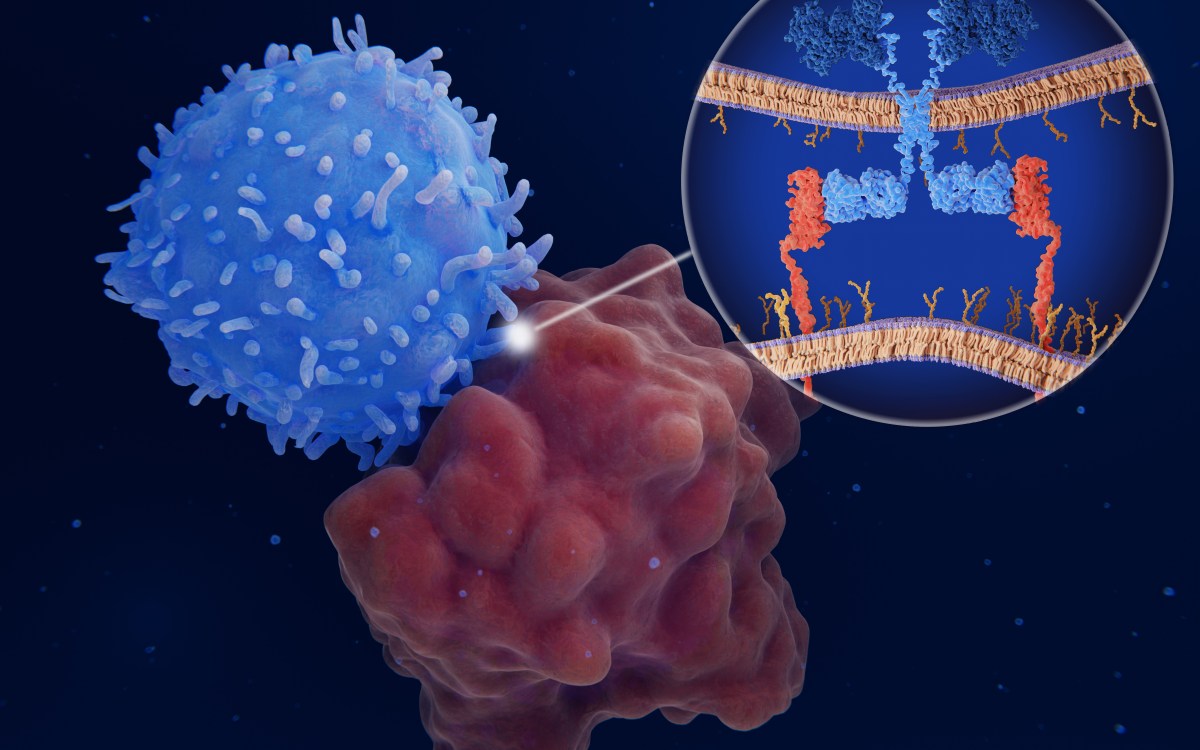

Despite the symposium’s cautionary tone, several speakers described AI’s potentially far-reaching effects on global health. Image analysis, a key aspect of disease screening and diagnosis, is an area ripe for rapid change. Lily Peng, product manager for Google AI, described Google’s work on diabetic retinopathy. The company’s researchers used a “deep learning” algorithm that reviewed thousands of images of both normal and damaged eyes and developed a screening tool for the condition — a side effect of poorly controlled diabetes — that performed as well as trained ophthalmologists.

That tool, and similar ones for other conditions, can provide valuable screening and referral services in rural areas that have little medical infrastructure. Their promise is of a future where initial screening can be guided by community health workers — far more numerous than trained physicians — who can then refer those who test positive to clinics and hospitals staffed with better-trained medical personnel.

But the question remained: How effectively would such interventions perform in the field? During a Q&A session, one participant described a device developed by an engineer in Cameroon to diagnose cardiac problems in remote areas. The device was designed to be used by rural nurses who could send results to city-based cardiologists for review. Problems occurred, however, because the nurses entered data in the wrong fields, spotty internet connections made it hard to transmit the data, and finally, when the information made it to the city, the cardiologists were often too busy to examine it.

Adam Landman, chief information officer at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and an associate professor of emergency medicine at Harvard Medical School, said it’s important that AI not be viewed as a solution in search of a problem, but that the health care outcomes be considered first and AI considered as one tool among others to address it.

“The key with any technology — and AI is just one of them — is it needs to actually solve a health care [problem],” Landman said. “The need [should] drive the use of it and not the technology drive the use. They may not need AI to start. In fact, they may not need any technology to start. They may need more people, more health care workers. There may be other things to invest in before technology, or technology may be part of that solution.”

About 50 experts in the use of artificial intelligence and other digital health care technologies gathered at Loeb House for the all-day symposium.

Ann Aerts, head of Novartis Foundation, said severe shortages of doctors and nurses in some parts of the world demand innovative approaches to health care. Technology has already transformed the way medicine is practiced in some resource-poor settings. In Ghana, a telehealth pilot has evolved into a national telehealth program that keeps a center staffed 24 hours a day, seven days a week, with doctors, nurses, and health workers. The program isn’t a substitute for skilled medical care, but Aerts said that about 70 percent of all health care problems can be solved over the phone. The program highlights how innovative solutions can be found to the health care shortage that is a fact of life in many parts of the world.

“This calls for innovating the way we deliver health services, for transforming our health systems,” Aerts said. “We cannot go back to the old model. It doesn’t work. … Let’s look at how we can reimagine the way we deliver health services.”

John Halamka, chief information officer at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the International Healthcare Innovation Professor of Emergency Medicine at Harvard Medical School, said that AI has the potential not only to meet needs where care is scarce, but also to improve care and reduce errors where doctors and nurses are present. He told of a woman who visited a doctor in northern India because of abdominal pain. She was incorrectly diagnosed and paid for repeated testing and physician visits. Ultimately, she was forced her to sell her house and cow, impoverishing her family.

She was finally diagnosed correctly with abdominal tuberculosis, a condition that might rarely be seen in the U.S., but ought to have been considered much sooner in India, which has 1.3 million active cases of tuberculosis, Halamka said.

Halamka consulted on another case, in Bakersfield, California, that shows the problem is not restricted to the developing world. A young woman was arrested for running naked through a Walmart parking lot at 3 a.m. When Halamka called to talk to the emergency room physician, he was told that the young woman’s urine had tested positive for cannabis, so he had discharged her.

“And of course all of us in this room know that cannabis consumption results in young women running naked through parking lots at 3 in the morning — never,” Halamka said. “We flew her to Logan [International Airport], brought her to Beth Israel Deaconess … [and she had] the worst case of meningitis any of us had ever seen. Again thinking back on AI, if we had [it trained by the experiences of] a million young women with altered mental status, how many would include cannabis as the primary cause? Probably, again, none. But in a person who lives with a lot of other 20-year-olds who have lots of infectious diseases, what are the chances of meningitis? Actually, pretty significant.”

Halamka said that artificial intelligence and machine learning has progressed rapidly since the late 1990s, when it took six months of work to get AI to recognize a giraffe as a mammal. Today, he said, designing an AI algorithm itself is relatively easy, but algorithms have to be trained on large amounts of data from past cases, and it can be challenging to ensure that data is available, appropriate, and unbiased.

“Gathering and curating good-quality data, unbiased data, and using it to train these algorithms is still a challenge,” Halamka said. “The quality of our data is poor. We get social security numbers wrong 11 percent of the time. We even get gender wrong 3 percent of the time. Men have babies, women have prostatectomies. We need to work on curated data sets if we’re going to be successful with AI.”

Designers of AI health care applications, Aerts and other speakers said, should also guard against AI becoming a benefit solely for the rich, a factor that increases inequality instead of helping close the gap between haves and have-nots. Ashley Nunes, a fellow at Harvard Law School, said there’s a perception that AI will cut health care costs, making it more affordable for the poor, but there’s no guarantee that will happen.

Nunes pointed to self-driving cars, which are projected to make roads safer. Accident data show the poor suffer the most physical and economic harm from road accidents, so hypothetically they could see the most benefit. But the added cost of the driverless technology means it will likely disproportionately benefit wealthier drivers, highlighting how important it is to ensure that tech solutions in health care benefit everyone.

Jha said he looks forward to a time when AI is just another tool in the health care toolbox.

“The whole idea of digital health reminds me that about 20 years ago we used to talk about e-commerce,” he said. “We don’t talk about e-commerce anymore; we just talk about commerce.”