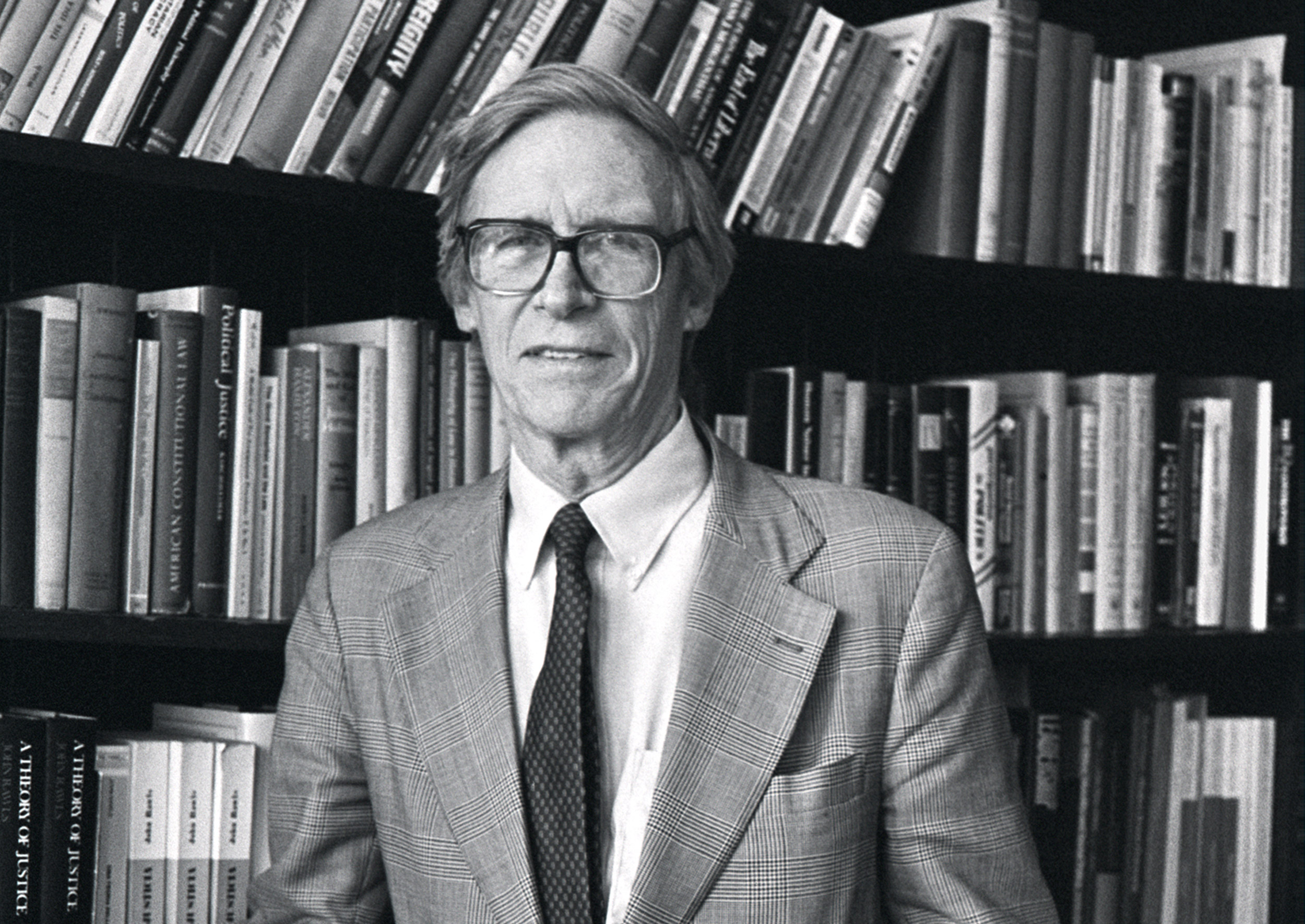

Jane Reed/Harvard file photo

A new look at the father of modern political thought

‘Inequality, Religion, and Society’ examines works of John Rawls

It’s been nearly 50 years since the political philosopher John Rawls published his groundbreaking “Theory of Justice,” articulating the connection between justice and equal rights. That 1971 book, the first of three major pieces by the onetime James Bryant Conant Professor who died in 2002, still stands as a defining work of modern political philosophy. This Thursday through Saturday, it and the links it identified will be the focus of “Inequality, Religion, and Society,” a conference at the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics.

With panel discussions tackling issues such as social inequality, economic justice, and religion and democratic society, the conference is particularly appropriate for today’s tumultuous politics, said its chair, Michael Rosen, the Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government. With keynote talks by Christine Korsgaard, the Arthur Kingsley Porter Professor of Philosophy, and Thomas Michael “Tim” Scanlon, the Alford Professor of Natural Religion, Moral Philosophy, and Civil Polity Emeritus, who had studied with Rawls, it will also offer a chance to look at the man as a historical figure, examining his development as a scholar and a thinker, from his years studying at Princeton to his nearly four decades teaching at Harvard.

It may have needed this long for a comprehensive examination of Rawls, whom many consider the progenitor of modern political philosophy. “As the environment of political philosophy has changed, so people have taken different aspects of Rawls’ work,” said Rosen. “All of us who worked in political philosophy have worked, in a sense, in his shadow.”

Rawls’ significance cannot be overstated, he said. “We’ve started to see … a degree of alienation from the liberal principles of pluralism and toleration he thought were essential to any kind of society.”

“All of us who worked in political philosophy have worked, in a sense, in his shadow.”

Michael Rosen

Rosen said the conference will question the applicability of work that dates from a very different time. After all, he noted, the world has not progressed as Rawls and his contemporaries expected. During Rawls’ time at Harvard, for example, many believed religion was a fading factor in global events. Today, “We’ve moved into a world in which we seem to face more religiously based conflict than would have been anticipated in the ’70s,” Rosen said.

Income inequality has also become more acute, trending against 1970s predictions. “Forty or 50 years ago, it was thought that, although there would be inequality in capitalist societies, that it would be moderate, and that there would be a rising tide, which would lift all ships,” said Rosen.

But while some expectations have not been met, Rawls’ work nearly half a century ago on climate change seems prescient. Specifically, Rosen said, “Rawls is one of the first people to raise issues about justice between generations in his work.”

Bringing together scholars from Harvard, Oxford, Cambridge, and other universities around the world, the conference will examine the resilience and utility of Rawls’ work. “We’re looking to see if there are ideas that are fruitful,” said Rosen. “But also how this context that we now face might force us to rethink and redevelop this great philosopher’s work.”

Rawls himself is now another focus of study. “People have started to ask scholarly questions about the development of his thought, about what his continuing motivations were,” Rosen said. “His own intellectual development is extremely complex and extremely fascinating.

“One of the most central discoveries is that in the center of his philosophy there’s a concern for how a liberal political order could accommodate a diversity of outlook and background, particularly of religion.” Rawls initially had been deeply religious, Rosen said, and, “In some ways, his later liberalism can be seen as coming to terms with aspects of his earlier self.”

The conference is supported by the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, Harvard’s Departments of Government and Philosophy, the Centre for Political Philosophy, Ethics and Religion at Charles University, and the Sekyra Foundation, both of Prague.