Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The election just ahead

A look at three local efforts to safeguard and understand the voting, while encouraging participation

The stakes in Tuesday’s midterm voting will be nothing less than the nation’s political and policy direction for the next two years. With polling often inaccurate in the last election, no one can confidently predict what the results will be this time, despite any evident trend lines going in.

Despite that uncertainty, many people, including at Harvard, are focused on the important voting ahead. Here are three major electoral areas — turnout, security, and voter analysis — in which efforts to understand the race and encourage participation are steaming ahead.

Future belongs to the young

Young voters, especially college students, are among the least likely to turn out at the polls on Election Day, no matter the year or the party in power.

The Harvard Votes Challenge, a student-led initiative that launched last spring, hopes to shatter part of that reality by helping University students register to vote, request and submit absentee ballots, provide helpful information, and get them excited about civic engagement and exercising their rights.

“Millennials and post-millennials are going to be the largest voting bloc in this upcoming election, and that’s really exciting,” said challenge co-founder Teddy Landis ’20, who also serves as student chair of the Harvard Public Opinion Project, which produces the Institute of Politics’ semi-annual youth poll. “Young people don’t really get a voice in politics, and so to see that we’d have all this potential presented a new beginning in America, in my mind. But then I looked at [data] which showed that young people don’t really vote. It was really sad to me that we have this tremendous opportunity to shape what we want our country to be, but young people aren’t taking advantage of that.”

The group is nonpartisan and has no public registration goal across the University, but hopes simply to encourage classmates to see voting — and more broadly, civic participation — as important components of what it means to be Harvard students, said Landis.

The initiative got an adrenaline shot as the semester began when new President Larry Bacow made voting in November his “homework assignment” for first-year students during his convocation address, said Landis, who oversees the College effort. Challenge team members took full advantage, slipping a problem set under every first-year’s door the day after Bacow’s remarks, instructing the 18-year-olds how to register to vote or how to request absentee ballots from their hometowns.

There are team leaders in 11 Schools. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) reached a self-imposed goal of registering 90 percent of eligible students through TurboVote last month, while the Graduate School of Education (GSE) had about 65 percent of eligible students register so far. In the College, 30 undergraduate teams have been holding events, knocking on doors, hosting sign-up tables, helping students request absentee ballots and get them mailed on time, and doing peer-to-peer outreach on why voting is important.

Kevin Ballen ’22 manages the first-year student drive and said he’s seen a lot of excitement among the students. The challenge hosted more than 40 study breaks since the semester began, posted information at most entryways to the Yard, and saturated social media. The challenge had 20 “dorm mobilizers” in first-year residence halls for one-on-one outreach and to help students navigate the logistics of registering and voting by absentee ballot, or to find out more about candidates and issues in their home states. In all, Ballen estimates the drive has contacted nearly 1,400 of the 1,600 first-years.

If results from a new Harvard Institute of Politics Youth Poll are accurate, turnout among Harvard students could reach a high. Forty percent of voters age 18‒29 say they will definitely vote in the midterm, according to the findings released Oct. 29.

With no way to track if or how students vote, the group won’t know until after the election whether its efforts have been fruitful. To gauge voter participation, the organizers have urged students to fill out pledge-to-vote cards, either in person or online, and are in a contest with Yale to rack up the most pledge cards. Behavioral science research shows that people are more apt to follow through on something if they’ve committed to it in writing.

According to a National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement report, 57.8 percent of 22,604 eligible Harvard students voted in the 2016 presidential election. More than three-quarters of eligible students, 77.6 percent, registered in 2016.

If results from a new Harvard Institute of Politics (IOP) Youth Poll are accurate, turnout among Harvard students could reach a high. Forty percent of voters age 18‒29 say they will definitely vote in the midterm, according to the findings released Oct. 29. Though poll director John Della Volpe said the organizers don’t expect that many to turn out, past trends indicate that, even accounting for the usual gap of -7.5 points between those who say they will vote and those who actually do, the figure suggests young voters will turn out in significantly greater numbers than in many years past. The only midterms in which young voters turned out at a greater rate than their typical 18‒20 percent were in 1986 and 1994, he said.

That could be bad news and good news, he said. It could be bad news in that what’s driving young voters to the polls is the “fear and trauma” they’ve experienced in their short lives. The poll found that two-thirds of young people polled (76 percent Democrats, 34 percent Republicans) are more fearful than hopeful about the country’s future. But the good news, Della Volpe said, is that such a large number of new voters would offer the country an opportunity for a “once-in-a-generation attitudinal shift” about voting and civic engagement.

Defending democracy, elections

U.S. intelligence officials are clear that Russian state actors interfered with the 2016 presidential election, in part by hacking computer networks belonging to political committees, candidates, and advocacy groups connected to the Democratic Party and to Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. Analysts say the hackers also infiltrated voter-registration rolls and some voting software and machines in dozens of states, and continue to run disinformation campaigns on social media. Thus far, the special counsel’s office has indicted 13 members of Russia’s military intelligence agency, the GRU, for alleged involvement in the hacking.

Recognizing how serious the hacking threat remains and how outmatched those working on the front lines of elections are (especially with Congress declining to take steps to protect election systems), the bipartisan Defending Digital Democracy project at HKS has been working to help campaigns, as well as state and local officials, identify and ward off threats to their electoral integrity.

Whereas the early focus of the project was getting state and campaign officials up to speed on the range and severity of cybersecurity threats, now the work centers on training officials to become self-sufficient in defending themselves.

In the ramp-up to the midterms, the project convened a military-style table-top exercise session for 120 officials from 38 states to simulate worst-case scenarios around cybersecurity and information operations and trained participants to run their own exercises in their states.

“I’d say on the whole there’s been improvement” since 2016, said Mari Dugas, the project’s coordinator, although nobody is ready to say they’re fully comfortable with the security of their voting systems, she added.

Though information operations are not technically part of state election officials’ jobs, the spread and influence of “fake news” and disinformation has had such an impact on voters that officials have asked the project for help detecting and responding to influence campaigns that seek to undermine trust in elections or mislead voters about how, when, and where to cast ballots.

On Election Day, participating students will observe and assist officials in five states. After the election, the project will convene a small, after-action review session at Harvard with invited officials to share what they saw, any threats they found, where security gaps may still exist, and to understand better any prevailing concerns ahead of the 2020 election.

Shifting ingrained attitudes on election processes has been a challenge, because some state officials have assumed that since they’re not from swing states or their communities are small, they’re unlikely to be targets. “We’ve seen that that isn’t the case. Anybody can be a target of these things, and have been,” so helping officials create a culture of effective cybersecurity will be key, said Dugas.

The voters’ own views

Political veterans were stunned by the 2016 election largely because the victory of Donald Trump shredded what many observers thought were the immutable rules of the campaign game about what worked with voters and what didn’t.

Trump’s win was one shift in a political landscape that has been rapidly changing in recent years. Accepted wisdom about who can credibly enter the political arena, about how candidates reach and sell themselves to voters, and about how they raise money and spend campaign funds no longer hold. The voters who once had to passively endure slick TV ads of candidates chosen by the two political parties now get to pick whose online pitches they’ll entertain from inside their personal information ecosystems.

Amid such rapid change, political analysts and practitioners have struggled to keep pace, especially since 2016 showed how off-track most had gotten. Many hoping to understand how voters think and behave now recognize that polling and opinion data aren’t delivering a rich enough portrait of where the electorate is moving ideologically, and why.

“For a long time, political actors and advocates were using polling, and that set of very small sample data was giving people directional impressions about which parts of America were moving which way, and that was the key guide to strategy,” said Laura Quinn, a visiting fellow at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at HKS and CEO and co-founder of Catalist, a voter data “utility” service. Catalist works with progressive left clients such as the AFL-CIO union and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee to tailor political advocacy messaging to voter segments across the U.S. electorate.

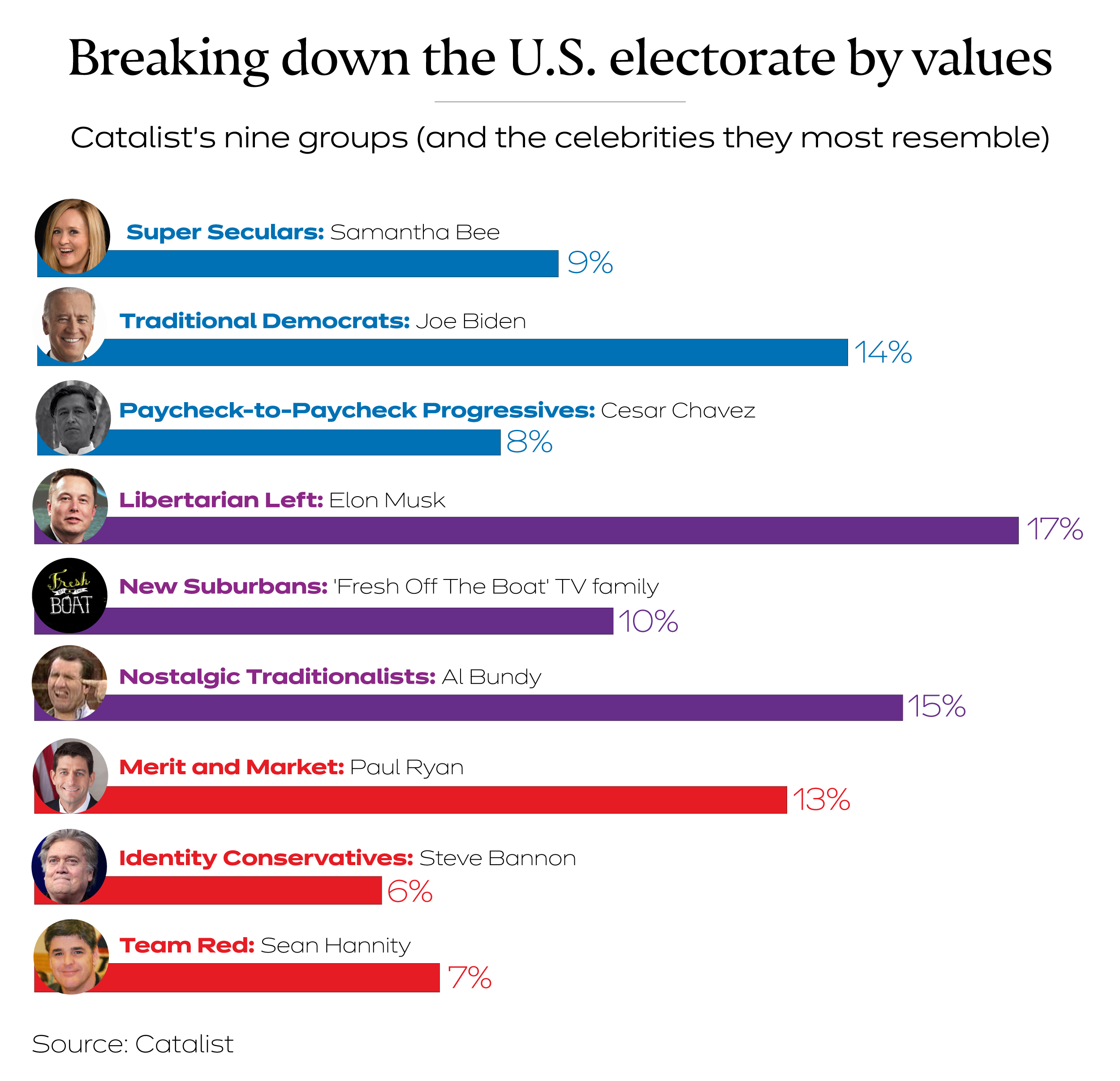

Now, with big data part of politics, Catalist tries to drill down into the electorate by analyzing not just the commercial findings and voter file information that all campaigns use, but surveys that elicit the broader viewpoints of would-be voters. So instead of asking questions about expected topics like the Affordable Care Act or gun ownership, which cause people to self-sort into partisan groups, Catalist asks about things that don’t signal an obvious right or left response, but gets at someone’s values. These are queries like “Is it morally good or bad to leave a dog out in the rain, or for a soldier to refuse to obey a potentially illegal order from commanders?”

The respondents are clustered based on their replies, not on their gender, age, income, or even supposed ideology. “Often in politics, we’re using pure demographics as proxies, and that really is not accurate,” said Quinn. For instance, “All women do not see the world the same way.”

With values, not demographics, as the baseline sorting mechanism, she says the firm is able later to superimpose data about voting histories, demographics, and past civic behavior to get a deeper, more-longitudinal picture of how groups view the world, what motivates them, and how they’re likely to act, as opposed to standard polling’s snapshot, moment-in-time approach. “There is no persuasion without understanding.”

Using the values methodology, Catalist has broken down the roughly 230 million voting-eligible Americans into nine groups, ranging from “super seculars” on the far left, represented by comedian Samantha Bee, to “team red” on the far right, embodied by Trump superfan Sean Hannity of Fox News.

The firm Cambridge Analytica was accused of using personal information from Facebook to target pro-Trump messages at millions of U.S. voters in 2016, based on five personality traits. But Quinn believes that a values approach to sorting voters is more predictive of civic behavior.

“None of these things perfectly explains why people are the way they are. People are complicated, and they change. It’s the constellation of things that you believe that give you a sense of the person,” she said.

By using values methodology, the researchers have found that the conventional wisdom about the importance of gender and age in determining voting behavior is often wrong.

“When we see how they’re voting and how they’re behaving in all the civic data that we have, urban young people and young people in counties with major universities are behaving very differently than people their same age who are not in urban places,” said Quinn.

One strong predictor of political attitudes and behavior is marital status. “Men and women who are married are closer in their voting pattern, and single men and women are closer in their voting pattern to each other, and the gender gap between them is smaller than the gap between married people and single people,” she said.

In a changed political environment, voters are much tougher to sell in 2018. Quinn said they’ll give candidates three to nine seconds to make their case in a video pitch before deciding to listen further or turn away. Regardless of party affiliation, listeners want something that feels authentic, unfiltered, and local, she said. In the midterms, Catalist has been working with advocacy groups on ballot initiatives in Michigan, Maine, and Florida, among others, to fine-tune arguments to different voter groups.

Still, Quinn said there’s much more work to be done to understand the electorate. Unfortunately, those spending the most time on it today are practitioners focused on the next election. That’s why academia, as well as those working in political advocacy, “have a big, big role to play in reorienting the ship.”

After the election, Quinn said she’ll examine who voted and for whom, and which parts of the electorate moved in which direction, and then re-analyze the economic conditions of values groups to understand any movement. She would like to evaluate where people get their information and study voters’ changed economic positions to see how such factors might influence their views and behavior.

“If this country is going to be governable, you’ve got to be able to convince, after an election, enough of the folks who are part of the losing party that this is still a country where we can collectively make decisions and occasionally cross the aisle,” she said. “Without that ability, it’s a democracy that’s really in trouble.”