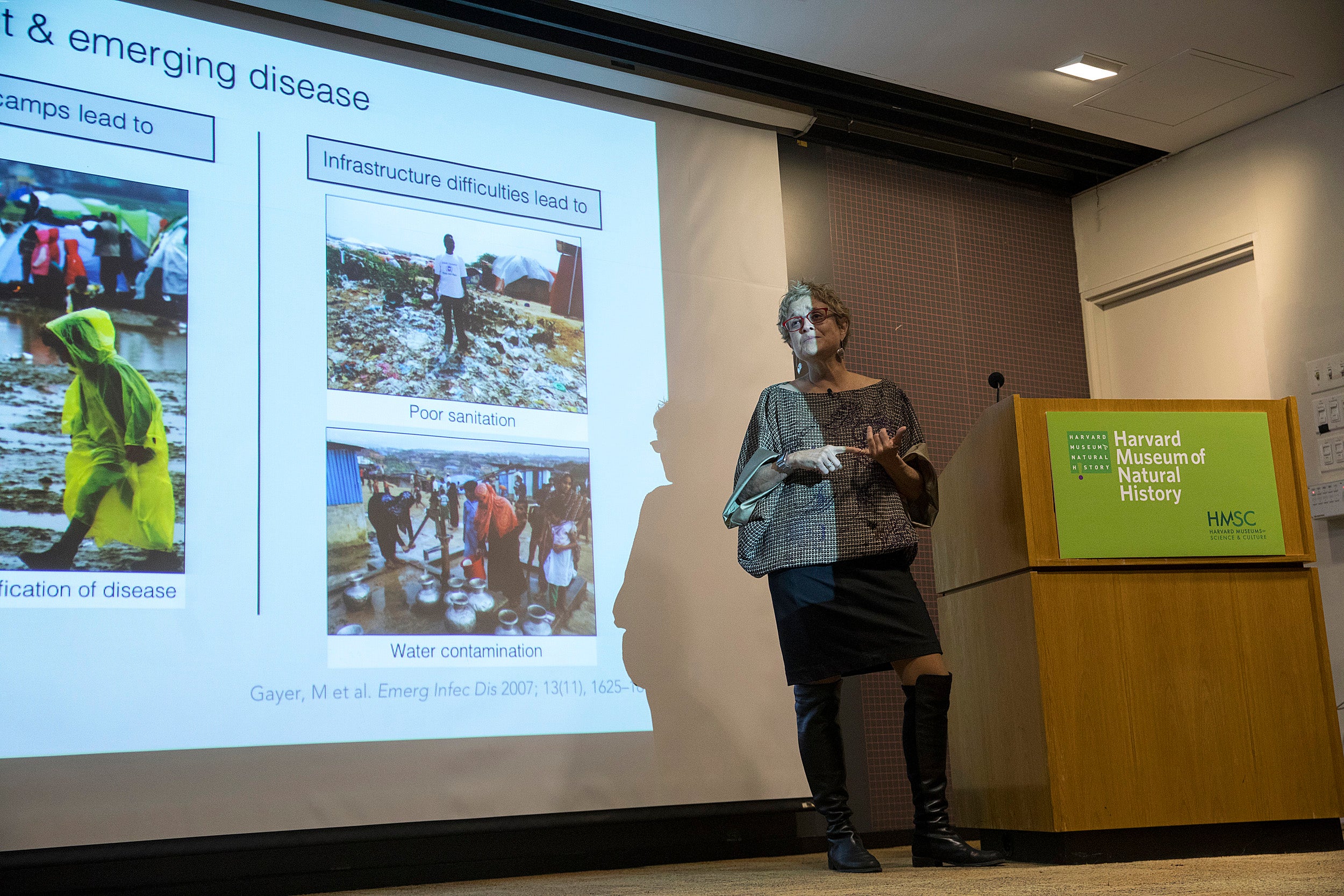

Stanford University’s Michele Barry outlines the political factors that contribute to pandemics.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Where there’s global unrest, there are often pandemics

‘Outbreak Week’ opens with talk on how diseases often spread unchecked

Pandemics are political, and the spread of disease is a common consequence of global conflict. In a lecture titled “Conflict and the Global Threat of Pandemics,” Michele Barry, senior dean of global health and director of the Center for Innovation in Global Health at Stanford University, examined the relationship between unrest and health crises.

Monday evening’s talk at the Geological Lecture Hall at Harvard Museum of Natural History was the start of Harvard Global Health Institute’s “Outbreak Week,” a five-day series of events to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. As Ashish K. Jha, dean for global strategy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, noted in his opening remarks, that pandemic remains the deadliest in history, though HIV has come close. He also outlined Harvard’s work with infectious diseases, notably its 2014 development of strategies to address the Ebola virus.

Barry, a specialist in tropical diseases, said she has long been interested in the development of pandemics. Defining a pandemic as “an infectious disease that spreads over countries or continents and infects large numbers of people,” she began her talk with a question: Why are centers of global conflict often the “hot spots” for emerging disease? Some answers, she said, are obvious: Vaccine availability gets interrupted by conflict, as does the scientific study of animals that may transmit disease. But she also outlined the more complex political factors that contribute.

In some cases, she noted, politics alone is enough to spread diseases. She cited a New York Times report from just two weeks ago, headlined “China Has Withheld Samples of Dangerous Flu Virus.” The new virus, a bird-borne flu called H7N9, has been evolving for more than a year. The story quoted Rick A. Bright of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services warning that, “There is nothing to hold it back or slow it down. Every minute counts.” Yet China has declined to turn viral samples over to the Centers for Disease Control to use in developing a vaccine, citing the Trump administration’s trade tariffs. Thus a new virus at this point is unchecked.

Barry offered a number of fairly recent case studies. Three of the first nations Ebola struck were Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, all of which had seen their infrastructure collapse after civil unrest, and trust in government erode.

During the 1992 civil war in Tajikistan, more than 100,000 citizens fled to Afghanistan and brought malaria, causing an outbreak of a disease that Tajikistan had eradicated. Yemen has seen a “horrific” cholera outbreak that could have been prevented easily, yet infrastructural collapse has kept the vaccine from becoming available. In Angola, which has seen 30 years of civil war, an outbreak of the Ebola-related Marburg virus has been exacerbated by the reuse of syringes as healthcare breaks down.

A further consequence, she said, is that drug treatment gets interrupted when infrastructures fail, sending resistance to vaccines up. Health care workers are also less likely to get proper training in such circumstances.

Recent months have also seen health care literally attacked. Since January there have been 149 documented attacks on doctors and hospitals, mostly in Syria. “This is the same atrocity that started the Geneva Conventions 153 years ago and led to the creation of the Red Cross,” Barry said. “It is the original war crime.”

The solutions aren’t always clear. Vaccines need to be distributed in times of conflict, but embedding health workers in the military or holding “hit and run” vaccine sessions during cease-fires can be problematic. Barry said governments can work together to strengthen incentives for reporting health crises and ramifications for silence.

While stronger infrastructure would help, the data isn’t always encouraging. Barry noted that the World Health Organization’s total current budget is $805 million, scarcely enough to build one hospital. “That’s a pathetic amount of money, and it should be the wake-up call,” she said. Quoting a former colleague, she closed by noting that, “Epidemics are inevitable, but pandemics are optional.”

“Outbreak Week” continues on Wednesday with a panel symposium on “Media in the Age of Contagions,” at Milstein West at Harvard Law School beginning at 10 a.m., and a screening of the film “Contagion,” with screenwriter Scott Z. Burns, at the Smith Campus Center at 6 p.m.