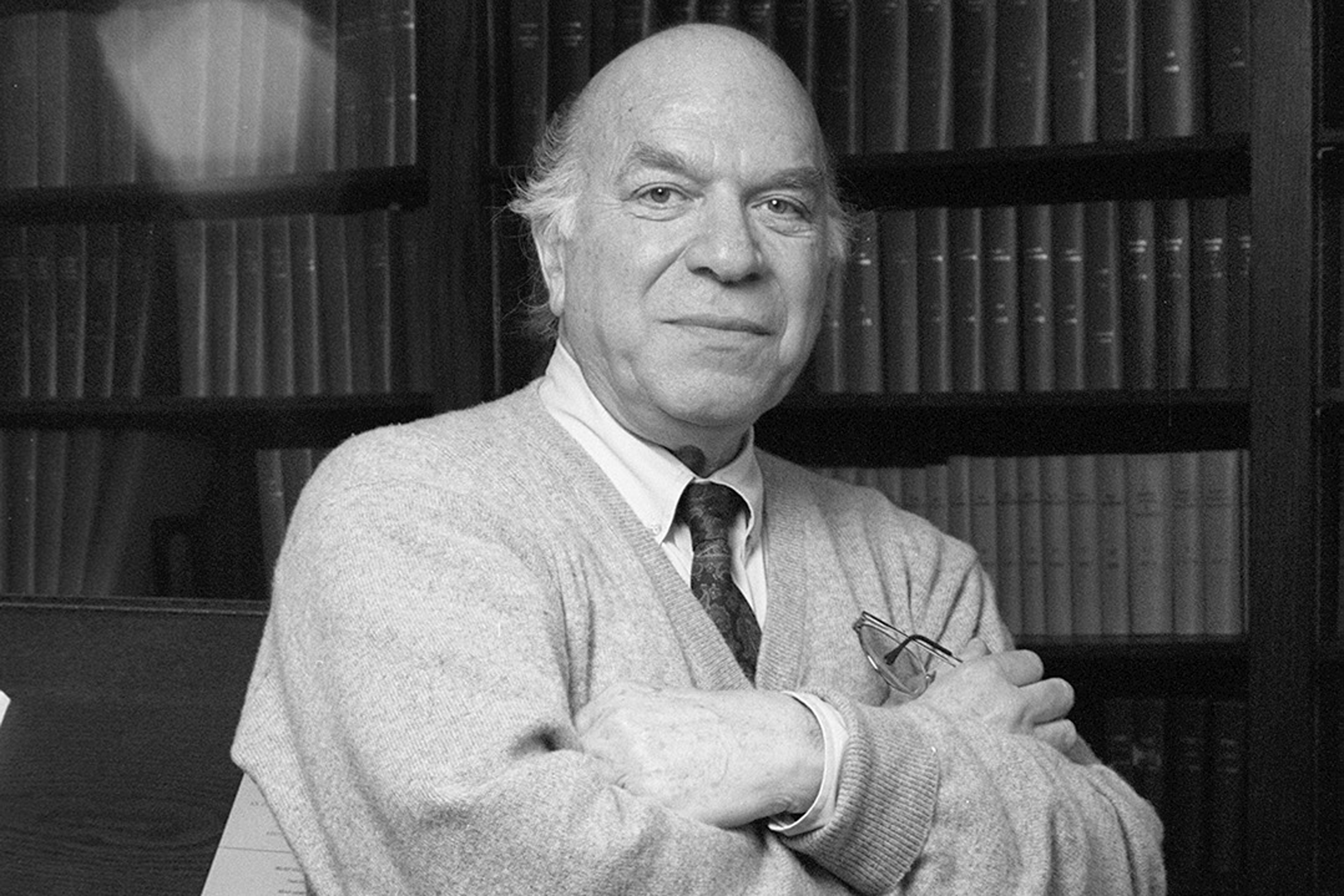

Colleagues of longtime Harvard professor and Film Archive co-founder Stanley Cavell discuss his legacy.

Harvard file photo

Remembering — and rereading — Stanley Cavell

In his writing and interests, Harvard philosopher roamed far beyond the academy

Stanley Cavell was no ordinary philosopher, especially when he wrote.

“The quality of his writing was rigorous, but also personal. He addressed the reader quite directly and, at times, intimately,” said Brian D. Young Professor of Philosophy Richard Moran, who recalled Cavell’s impact on him as an undergraduate — years before they would become friends and colleagues.

“As a young person first discovering philosophy, you have to acquire the habit and the pleasure of rereading the texts, and continuing to learn from them. For me the richness and intensity of Cavell’s writing continually rewards that attention and was a major part of my education in philosophical reading. It is these same qualities that enabled Cavell’s writing to gain such a wide audience outside of academic philosophy.”

Cavell, Walter M. Cabot Professor of Aesthetics and the General Theory of Value, Emeritus, died June 19 in Boston at 91. A faculty member for decades and a co-founder of the Harvard Film Archive, he published 18 books, including “Must We Mean What We Say?,” “Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage,” “The World Viewed,” “The Claim of Reason,” and “Disowning Knowledge.”

“I first discovered Cavell’s writing in the 1970s, and his originality and range as a philosopher made a deep impression on me,” said Moran. “Today it is perhaps easy to forget or take for granted how pioneering he was. Academic philosophy has expanded and changed since the ’70s, but at the time there was hardly anyone writing across the gap between analytic and continental traditions, much less making movies, or Thoreau, or Shakespeare topics for serious philosophical reflection. He changed the possibilities of philosophical writing.”

Born in Atlanta to Jewish immigrants, Cavell enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, at age 16, graduating in 1947. A talented jazz pianist, he briefly attended the Juilliard School in New York before returning to the West Coast to take psychology and philosophy courses at UCLA. He completed his doctoral studies at Harvard and joined the faculty in 1963, as Civil Rights activism intensified on campuses nationwide. He taught in the Freedom Summer voting rights effort at Tougaloo College in Mississippi in 1964, and helped a student-driven campaign at Harvard to found the department of African-American studies.

“At the time there was hardly anyone … making movies, or Thoreau, or Shakespeare topics for serious philosophical reflection. He changed the possibilities of philosophical writing.”

Richard Moran, Brian D. Young Professor of Philosophy

Film was never far from Cavell’s mind, as he explained to a UC Berkeley interviewer in 2008.

“What’s kept me going,” he said, “was the sense that it was not a question of why I was interested in film, but a question of why, since everyone is interested in film (one supposes throughout the world), why don’t philosophers write about it? That was the question that, perhaps, more than anything, puzzled, bothered, even provoked me.”

Along with film scholar Vlada Petric and documentarian Robert Gardner, Cavell co-founded the HFA in 1979.

“Stanley so facilitated a pleasurably logical bridge across Quincy Street that connected the humanities in Harvard Yard to the then-new Carpenter Center,” said Steven Brown, a onetime Cavell student who now manages the archive’s box office. “The arts are integrated into the practice of teaching humanities much more deliberately now, but this was not such the case in the ’80s when I took his ‘Moral Perfectionism’ course.

“In the Harvard Film Archive, cinema came into the classroom and vice versa. And it was done with such élan and without a whit of pretension.”

Cavell in his office in 2004.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Cavell made a “profound” impression in the classroom, said Moran. “His work and support of students extended many, many years after they graduated, and he left his mark on many people outside philosophy.”

Those people included the film director Terrence Malick ’65, Moran added.

Literature was another Cavell passion, expressed powerfully through his engagement with Shakespeare. His first essay on the plays, a 1966‒67 study of “King Lear,” marked an influential beginning to decades of writing on the Bard and other literary giants.

“Cavell made contributions to classic philosophical problems such as the understanding of philosophical skepticism, and to the understanding of canonical philosophers such as Wittgenstein and J.L. Austin,” said Moran. “But in bringing them into dialogue with figures like Beckett or Wordsworth, he also brought out the literary side of philosophical texts as well as what is philosophical in poetry, drama, and film. His writing is like nothing else in philosophy.”

A memorial service and conference to honor Cavell will be held at Harvard in the fall.