Harvard Business School Professor Francesca Gino talks about what she learned from the talented rebels she’s worked with during her research over the years, and what they have to teach us about when to break the rules.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Unleash your inner rebel

In an age of constant change, it pays to be trailblazer, Harvard author says

In today’s relentlessly competitive business climate, the riskiest strategy of all may be to play it safe. Coming up with a smart idea or a great product may no longer be enough, because if you’re not constantly moving forward you’re falling behind.

But along with the buzzwords like disruption and innovation that often define success in the digital age are others that make many people uncomfortable — like change, nonconformity, and trailblazer. And that just shouldn’t be, says Francesca Gino, the Tandon Family Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. After all, embracing discomfort, thinking unconventionally, and breaking established norms are what produced innovative film director Ava DuVernay and Apple CEO Steve Jobs, and unleashed pioneering companies such as Pixar and Google.

Gino draws on her experiences studying the behavior of business leaders and organizations in her new book, “Rebel Talent: Why It Pays to Break the Rules at Work and in Life,” to identify the common traits and practices among successful renegades that give them their creative and competitive edge.

In a conversation with the Gazette, Gino explained what rule-breakers do that makes them successful, and the steps people can take to tap into their inner rebel.

Q&A

Francesca Gino

GAZETTE: In the book, you talk about rebels as people who practice “positive deviance.” What do you mean by that, and where did your interest in this topic come from?

GINO: For many years, I studied people who cheat and behave dishonestly in organizations, as well as how organizations might prevent problematic rule-breaking. As I was doing this research, I came across stories of people who were breaking rules in a way that created positive change in their organizations and in the world. This type of “positive deviance” involves rule-breaking that’s productive rather than destructive.

I vividly remember the moment when I realized I wanted to write this book. I was browsing the shelves of the Harvard Coop bookstore and came across a book titled “Never Trust a Skinny Italian Chef.” As I flipped through the pages, I saw beautiful pictures of dishes that didn’t resemble any of the traditional meals I had while growing up in Italy. In Italy, a country that reveres tradition, recipes are passed on from generation to generation, and you just don’t mess with them. But the Italian chef Massimo Bottura, who wrote the book I was perusing, did exactly that. He studied traditional Italian recipes carefully, but then transformed them into innovative dishes. His three-Michelin-star restaurant, Osteria Francescana, was named the best restaurant in the world in 2016. Rather than breaking rules destructively, he did so constructively. I wanted to learn more about how he did it and how the rest of us can do the same.

GAZETTE: You suggest anyone can be a rebel talent. But isn’t a key reason why people put up with the rebelliousness of a Steve Jobs or a Chef Bottura because of their extraordinary talent and track record of successful boundary-pushing? They’ve proven their iconoclastic ideas work.

GINO: You don’t have to be born a rebel. All of us can use our talents more often in the same way as the successful people you’ve mentioned. In studying rebels across all sorts of businesses, I tried to identify their secret recipe, and came up with five talents that they seem to share: novelty, curiosity, perspective, diversity, and authenticity.

We all have the potential to be rebels, but it’s not easy to break rules. Rebelling means leaving behind what’s comfortable, familiar, and known. It means fighting against what comes naturally to us as human beings — the status quo. Rather than taking traditions or existing procedures for granted, rebels like Chef Bottura question them to create something new. When Greg Dyke became the general director of the BBC in early 2000, for example, he found an organization that was very much troubled. Conventional managerial advice would encourage him to lay out a clear vision and then figure out how to delegate to execute it. Instead, he spent five months traveling to various BBC offices in the U.K., even the most remote ones, where he’d show up in the cafeteria and ask employees how he could be helpful and how they thought the BBC needed to change. Rather than giving orders and dictating answers to the problems he saw, he asked questions. By going against what others expected he would do, he gained everyone’s respect. By the time he set a vision for how the organization should change, employees were eager to help him in the mission.

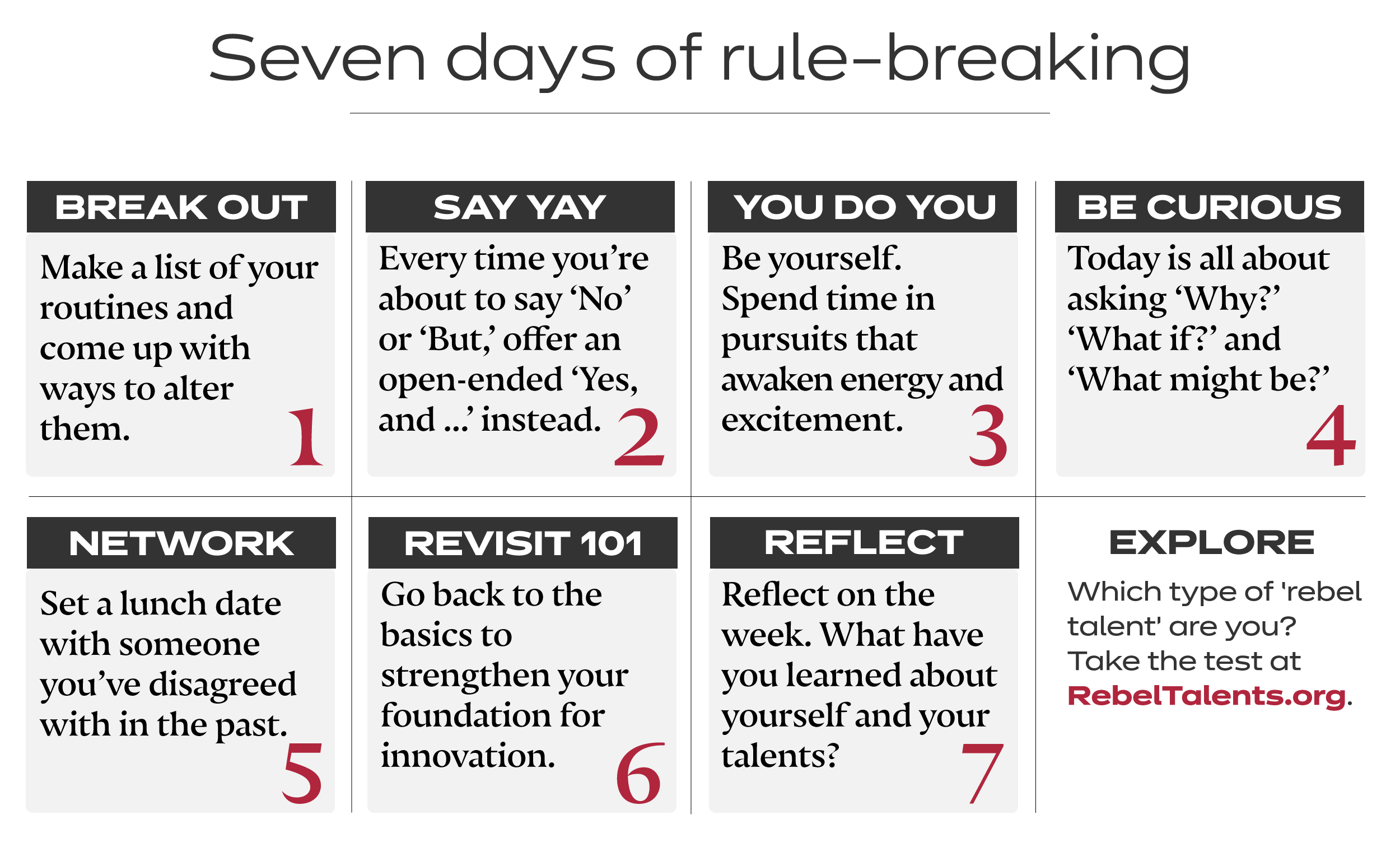

Source: “A Week Living Like a Rebel,” Francesca Gino; Graphic by Rebecca Coleman/Harvard Staff

GAZETTE: How do you know when it’s appropriate to push outside of the boundaries and when not to?

GINO: For me, it’s about getting into the habit of using the five talents more often. I’ve developed a test that people can use to find out which talents come more or less naturally to them. I also offer tips you can use to bring out other talents more often. But you’re right. It’s a matter of using your judgment when it comes to rule-breaking. Organizations that have done this successfully make it clear when rules should be broken and when they should not. The leaders of Ariel Investments, a Chicago-based money management firm, encourage rebellion in all sorts of ways. They want people to be authentic, which includes feeling free to disagree with and challenge each other, but everyone in the firm knows which rules should not be broken. For example, before a letter goes out to a client, three people must review it to make sure that it’s clear, because the company’s reputation with its clients is so important. Clarity about rules such as this one helps people know when it’s an appropriate time to break a rule and when it is not.

GAZETTE: Isn’t it difficult to be rebellious at work when management typically rewards conformity to specific standards, and human resources often hires for, among other factors, “fit”?

GINO: When leaders and organizations encourage people to break rules, people trust that the company is giving them a chance to use their talents and make decisions, including when and when not to break rules. It’s true that many leaders say they value rebellion and rule-breaking, but don’t encourage it for fear it’ll result in chaos. I have met many leaders who, in the end, push for conformity because of this fear. But I’ve also met leaders who have modeled rule-breaking and encouraged it in their organizations quite successfully.

One of the companies that comes to mind is Intuit. Every year, the firm gives out awards for great innovations that employees have come up with. But there’s also an award for the best failures: explorations that didn’t turn out well, but that allowed the company to learn. The failure award even comes with a failure party. This sets up a system where people are comfortable breaking rules: They’re comfortable exploring and being curious, as they know they won’t be punished for experiments that didn’t turn into innovative ideas. But as they explore, they’re using their judgment.

GAZETTE: You identify eight principles of rebel leadership:

- Seek out the new;

- Encourage constructive dissent;

- Open conversations, don’t close them;

- Reveal yourself and reflect;

- Learn everything and then forget everything;

- Find freedom in constraints;

- Learn from the trenches;

- Foster happy accidents.

Why are these critical and how would one incorporate them in everyday life or at work?

GINO: In identifying the principles of rebel leadership, I was inspired by the principles at work on pirate ships during the 16th century. Before a pirate ship left port, the crew would agree on a set of “articles” they would follow during the trip, which made up what they called a constitution. Pirate ships were very diverse organizations at a time when slavery still existed in the United States. What mattered most were your skills and contributions. The captain was elected by the crew, but the crew could remove the captain if he wasn’t treating the crew well or was taking more than his share of the loot. The pirates largely did away with hierarchy and took steps to encourage their captain to be humble. Rebels treat others those around them as if they were on equal footing — no matter how hierarchical the organization is.

One of the eight principles of rebel leadership — in essence the articles for modern-day rebels — is “Learn everything and then forget everything.” This is language that Chef Bottura uses. Rather than disrespecting traditions and breaking rules simply for the sake of it, effective rebels study traditions and rules carefully. They have a deep understanding of “the basics.” Before reinventing beloved Italian recipes, Bottura spent months studying them and asking a lot of questions about why things were done the way they were.

Another principle is “Foster happy accidents.” The idea behind this is to put some thought into making sure that happy accidents happen, whether it’s a new idea that comes from a mistake or a collaboration between people from different backgrounds. Bottura did this by hiring people from different countries to fill his kitchen so that they’d bring different ideas and perspectives to the table (including a Japanese and an Italian sous chef). Steve Jobs created happy accidents when he designed the headquarters of Pixar Animation Studios to have a large, open atrium equipped with a cafeteria, a gift shop, and screening rooms — places where people who do not usually work together could run into one another and strike up conversations.

GAZETTE: You say “rebels realize that stereotypes are blinding and that fighting the tendency to stereotype produces a clearer picture of reality — and a competitive advantage.” How are rebels able to stop themselves and see around stereotypes if confirmation bias is essentially unconscious?

GINO: Rebels are well aware of how stereotypes may influence their actions. They actively fight against them and against conventional social roles. Rebels put themselves among people who think differently or who might have a different perspective. This allows them to leverage their differences and, in a sense, train their minds to avoid holding stereotypical views in the future.

At Osteria Francescana, the various components of a dish need to be plated with the precision of a surgeon. One of the restaurant’s cooks is a person who’s almost blind. Common stereotypes would lead us to believe that this person would be unable to do the job properly. And yet he was helped by the team, had a lot of passion, and was able to do his job quite remarkably. Rebels don’t accept stereotypes: They fight them and they look at the world a little bit differently.

GAZETTE: What do you hope people take away from this idea of rebel talent?

GINO: Rebelling means being willing to take risks that can be uncomfortable. I hope readers will become more comfortable being uncomfortable. I hope they’ll use their personal talents more often, whether at work or in life. If you’re like me, after trying the rebel life, you won’t want to go back. When we rebel, we find more enjoyment in work, play, and interactions with others. My book offers tips on how to break the rules in productive ways, a skill that may people lack. If you told me in a couple of months, “I’m using your guidelines for living like a rebel — as a result, I find myself smiling more often and getting more satisfaction out of my job,” that would make me happy. It would mean that the message of the book is changing people’s lives for the better, in big and small ways.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.