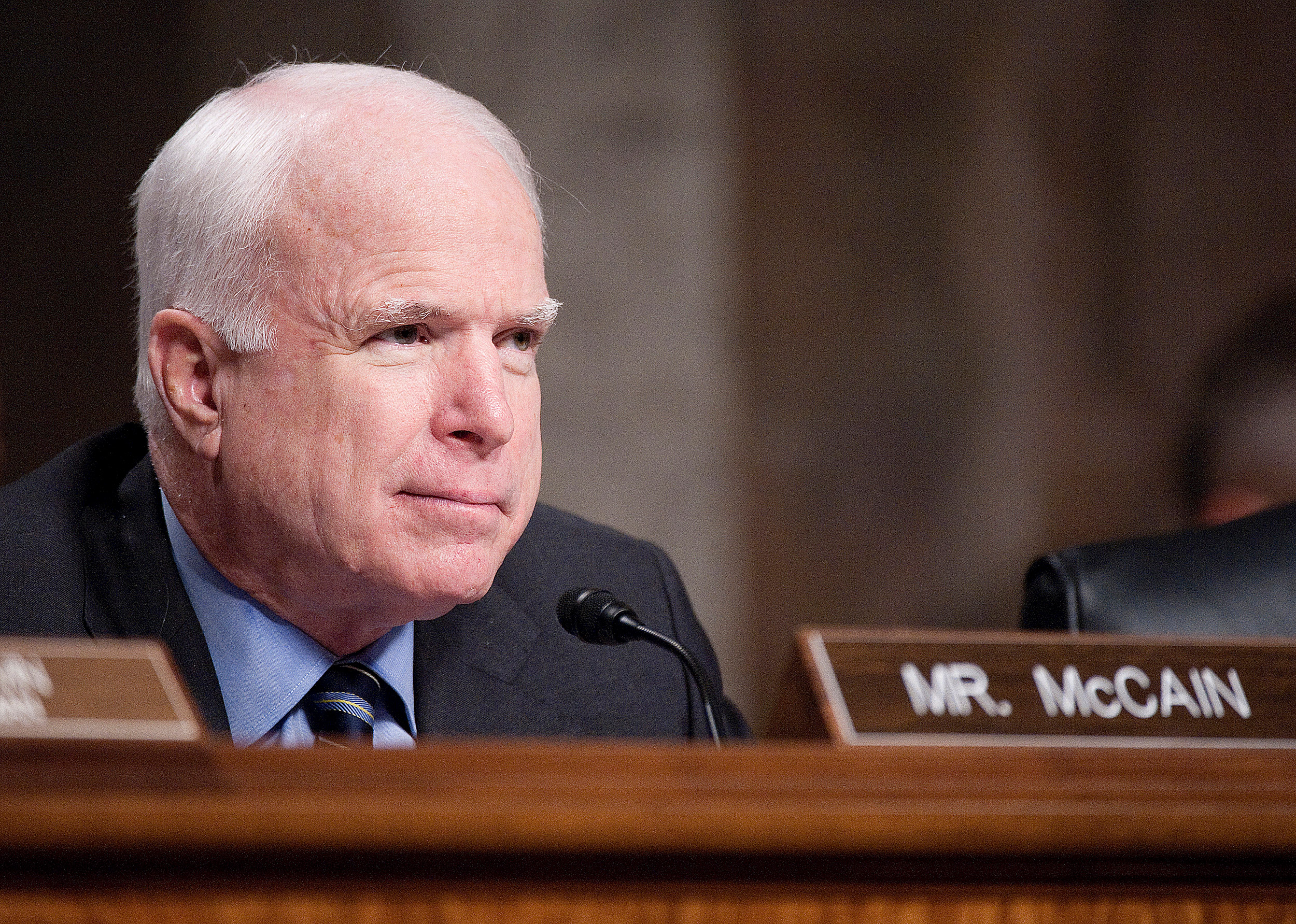

Sen. John McCain announced this week that this will be his final term in the Senate.

Photo By Bill Clark/Roll Call

John McCain: A maverick who matters

Harvard analysts recount legacy of ailing senator, who says it’s his last term

There are few people who can say they’ve spent a lifetime, more than 60 years, in service to the United States.

John McCain is one of them.

Like his father and grandfather, who were both admirals, McCain, 81, graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, and then he went into combat during the Vietnam War. A decorated pilot, he flew bombing missions until the North Vietnamese shot down his plane over Hanoi.

For 5½ years, McCain was held captive under brutal conditions, and tortured. He was released in 1973. After retiring from the Navy because of permanent injuries from his imprisonment, McCain entered politics in 1982. He served two terms in the U.S. House before winning election in 1986 to the U.S. Senate, where he has served six terms representing Arizona. He ran unsuccessfully for president in 2000 and was the Republican Party’s nominee in 2008.

Last July, McCain announced that he had glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer. He has been in and out of the hospital undergoing treatment ever since. In an excerpt from an upcoming memoir, he announced this week that this will be his final term in the Senate.

“I don’t know how much longer I’ll be here. Maybe I’ll have another five years. Maybe, with the advances in oncology, they’ll find new treatments for my cancer that will extend my life. Maybe I’ll be gone before you read this. My predicament is, well, rather unpredictable. But I’m prepared for either contingency, or at least I’m getting prepared.”

Sen. John McCain, in his new memoir, “The Restless Wave”

Known for his sometimes-irascible demeanor and salty humor, McCain often bucked both Republican Party dogma and conventional political wisdom, earning him a reputation as a maverick. Though his independent streak could rub some people the wrong way, few have ever questioned his sacrifices and commitment to serving the nation.

The Gazette spoke with Harvard-affiliated analysts about the man they know, his longtime influence, and the legacy he will leave behind.

The McCain they knew

DAN BALZ

Chief political correspondent for The Washington Post; Institute of Politics 2017 fall fellow

I think he’s operated with a different compass than many politicians do. He’s always been willing to be outspoken, to work across party lines in ways that not everybody is these days. He has an independent streak; there’s no question about that. He had a very good working relationship with Ted Kennedy. They couldn’t have been more different, but he was motivated by a desire to get some problems solved rather than always scoring political points. He can be partisan, certainly, and he would be the first to say he’s not a saint, in terms of politics. He’s not afraid to offend people, sometimes to a fault. I suppose when you’ve lived the life he lived, particularly the years in the prison camp in North Vietnam, you come out of that with a different sense of how you’ll operate than somebody who might not have that experience. I think he probably realized that all your days are short and, if you’re in a place where you can accomplish things, you ought to do whatever you can to do that.

ASH CARTER

U.S. Secretary of Defense, 2015‒2017; co-director of the Belfer Center at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS)

I think he is regarded, certainly by me, but also by everybody else in the Defense Department I knew, as an authentic American hero and, second, as someone who has always put the institution of the Department of Defense and the U.S. military first. He holds it to high standards. He’s demanding, but integrity and accountability were important to him. There were times in which that stung, because when we made a mistake, he would be critical. But that was always fair. I have had a good personal relationship with him for many years. We had disagreements about what to do, but it was never personal. He was demanding because he thought the military of the United States of America ought to uphold up the highest standards, and he’s absolutely right.

E.J. DIONNE Jr. ’73

Author; columnist for The Washington Post; William H. Bloomberg Visiting Professor at Harvard Divinity School

The difference between a maverick and a disrupter like [President] Trump is McCain has actually wanted to drain the swamp. One of the consistencies that’s flowed through McCain’s career is a frustration with lobbying, with big money in politics — the major reform bill over the last 20 years, McCain-Feingold, bears his name for a reason. And so while some Trump officials might want to paint McCain as “establishment,” he’s actually in many ways a more authentically anti-establishment figure than they are.

Second, McCain has frustrated liberals over the years because he is essentially a very conservative man. Liberals have been frustrated with him over, for example, the war in Iraq and foreign policy. But no matter how frustrated liberals have ever been with him, there’s no one I know — other than Donald Trump — who downplays McCain’s heroism or the contributions he made to his country. In a deep way, I’m a McCain fan despite disagreements I’ve had with him over the years on certain issues, because he was authentic, and he is an authentic hero. The sacrifices he made are not a one-off; they reflect something that’s deep inside him. I’ve always liked McCain for how much the word “honor” matters to him.

DAVID GERGEN, L.L.B. ’67

Former aide to Presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton; director of the Center for Public Leadership at HKS

The John McCain story is ultimately one of inspiration, not legislation. He did, and has, in his later years, obviously become a figure of admiration because of the leadership he’s shown on health care and other issues.

He was here at the Kennedy School during the George W. Bush years. The students were curious about hearing him, but before that they just wanted to touch him. There was something that was magical about that presentation. And I think it was mostly about his heroism and the war. He was a POW, and there was the fact that the North Vietnamese knew who his father was and came to him early on to offer him a way to go home. And he said, “I’ll only go if my men go with me.”

Does he have a roustabout quality to him? Absolutely. Did he have some playboy qualities to him early on? Absolutely, although I don’t remember him ever treating women dishonorably … He was a guy’s guy there for a long time. He was a fun person to go out with. Hillary Clinton loved to go out and knock down a few drinks with him.

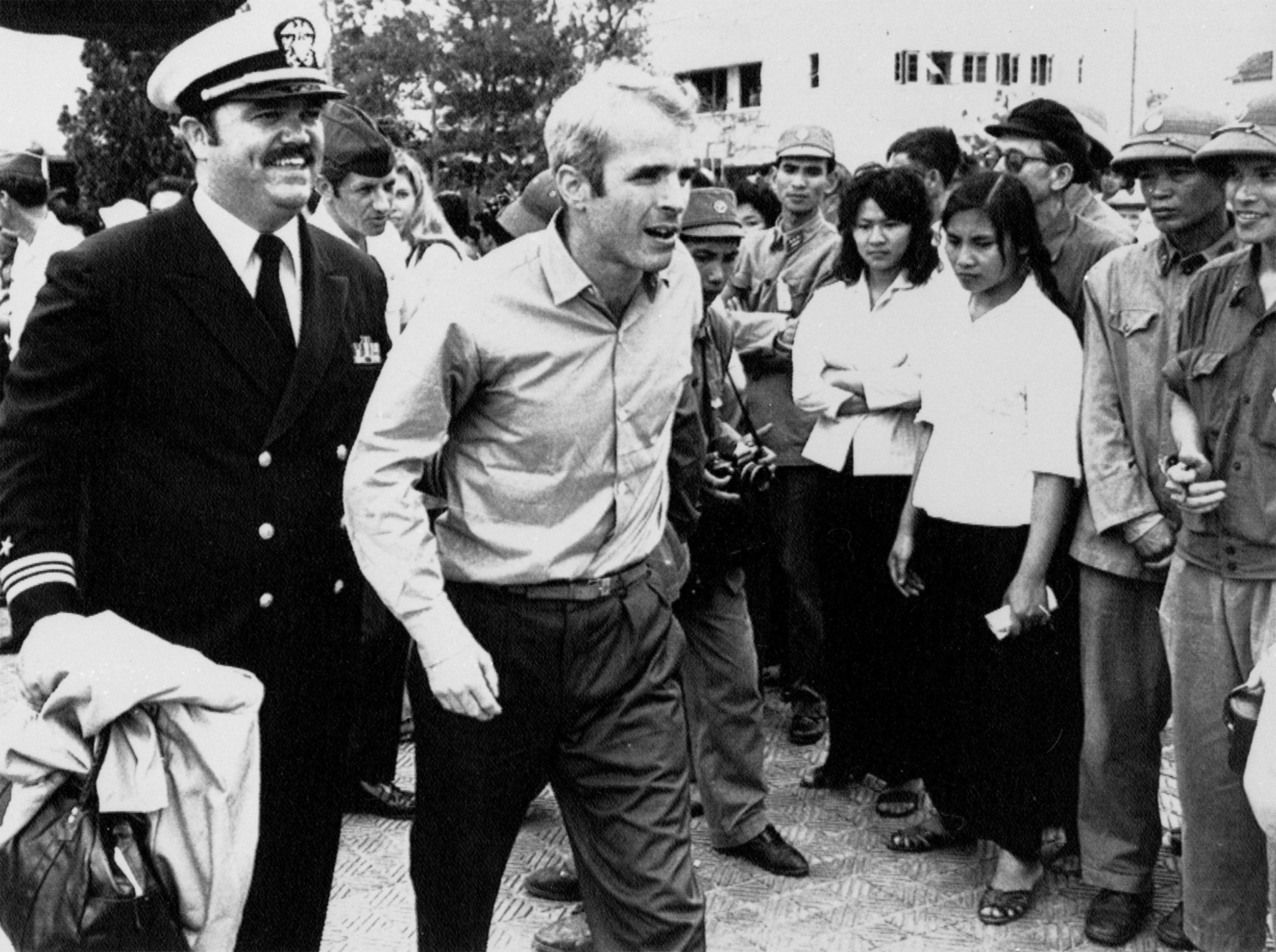

John McCain is escorted to Hanoi’s Gia Lam Airport on March 14, 1973, after his release as a POW.

AP Photo/Horst Faas

The military watchdog

JASON CHAFFETZ

Former U.S. Rep. (R-Utah); IOP 2017 fall fellow

His dedication and unwavering commitment to the U.S. military, his push to make it as strong and viable as it possibly can be — he has a long record of consistency in that category. He cared about how we use our military, weapons systems that we pursue, and how we use our military overseas. How many Sunday shows has he been on talking about the problems in the Middle East or Iraq and Afghanistan, and what should the strategy be? And the way he carried himself, he’s been a perennial power.

CARTER: He has influenced the department and secretaries of defense now going back several decades, so it’s not just me. First, he was a strong supporter of my efforts to reduce waste and improve the performance of the weapons-buying process. The Air Force tanker competition, which had been the largest procurement in DoD history, had been botched, and it was my job to handle that in a way that didn’t involve waste or corruption. It was a competition in which the two contenders, Boeing and Airbus, were running ads in the Washington, D.C., subways, somehow imagining that that would affect what I did. We don’t run our system that way, but I needed protection for the integrity of the procurement system, and John McCain provided that from Congress. And I’m very grateful for that.

The joint strike fighter — it was a mess. When I came into the department in 2009, John was extremely critical about it. He agreed with me that it was a mess, and he was very demanding. But I welcomed that because even when he was standing over you and breathing down your neck, if you were doing the right thing, he was a tremendous source of support. Over the last eight years, nine years now, DoD never had a budget. He wanted an adequate defense budget, but he also wanted to make sure there was no waste. He was for stability in how the government conducted itself, and I was really glad of that.

The foreign-policy strategist

PAULA DOBRIANSKY

Former U.S. ambassador; senior fellow at the Future of Diplomacy Project at HKS

I came to know Sen. McCain when I was undersecretary of state for global affairs. This began with his pivotal involvement in dealing with Ukraine’s 2004 flawed presidential elections. Since then, McCain has played a major role in highlighting the strategic importance of Ukraine and the need to counter Russia’s revanchist actions, including the illegal annexation of Crimea and ongoing aggression in eastern Ukraine.

Sen. McCain will long be remembered for his fierce and passionate defense of universal freedoms and the need to pursue a foreign policy that incorporates those core values. He has also been a tireless advocate of upholding the international rules-based order, which has preserved peace, stability, and security post-World War II.

CARTER: Where McCain has been extremely influential his whole career is in the Asia Pacific. Unlike the Middle East, the Asia Pacific is America’s future. It’s half of the world’s population, it’s half of the world’s economy, and it has been peaceful, by and large — the sole exception being the Vietnam War, which was an insurgency, not a major-power war.

It was America’s consistent military presence there that provided the balance wheel for the Koreans, the Japanese, the Vietnamese, the Chinese, the Indians — despite their differences among themselves, there was stability there. John McCain was one of the architects and consistent supporters of that. He traveled to the region. He would meet with the leaders there through many administrations. Administrations turn over. John McCain didn’t turn over [laughs]. So he was a sign and a symbol of American commitment to something that I thought was very important: that we remain committed to in a world where the Middle East, which is fundamentally much less consequential, grabs the headlines all the time.

With respect to the war on ISIS, which is one of the principal things I had to do as secretary of defense, John was constantly prodding and pressuring the administration and President [Barack] Obama. We needed to get serious about destroying ISIS. He hauled me up, and [Gen.] Joe Dunford, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, eight or nine times. These were difficult sessions, but I actually welcomed them because they prodded us and probed us to do more. Of course, we had a country that was tired of Iraq and tired of Syria, and we had a president who had campaigned on getting us out. But that wasn’t possible because barbarism had taken root, and people were attacking our people, and it had to stop.

And so I was grateful for all those hearings. They were not pleasant, but he was doing the right thing. He was overseeing us in an area where he believed — and I shared his belief — that we had to do something and the country had to be pulled in the direction of war.

The candor with the press

BALZ: He would disagree that he has always been the press’ favorite. He certainly did not feel that way about the 2008 presidential campaign [when McCain was the Republican nominee]. He felt that then-Sen. Obama got much more gentle treatment by the press than he got. But he has always been quite accessible to the press for as long as I’ve known him, which is 30 years, I guess. And particularly back in the ’80s and ’90s. McCain is the kind of person who wasn’t one to hide behind being off-the-record or anything like that. You interview him, you ask him questions, and he answers them, and generally in a forthright way.

When he did the “Straight Talk Express” in New Hampshire in the late summer of ’99, he would invite reporters to ride the bus with him. He would sit in the back, and he would take questions for as long as people wanted to ask them. He didn’t go off the record much, if at all. And for reporters that’s a refreshing thing to deal with, politicians who cooperate that way. So for that reason, he got to know a lot of reporters. Reporters were friendly with him. Unlike many politicians, you didn’t have the feeling that he was constantly guarded in the way he was dealing with reporters.

McCain’s got a wicked sense of humor, and often a sarcastic sense of humor, and he uses it to rib his staff and rib reporters, so there was a give-and-take that everybody enjoyed. But the more important thing is you could ask him anything and he would answer it. I remember one day, I realized I had to write a story, and so I had to get off the bus because he would go on and on and on. You’d never get any work done! Sometimes he’d say something witty or sarcastic or not perfectly politically correct.

I asked him some years later: If he were running today, would he do the Straight-Talk Express, and he said no, because the nature of politics has changed, the nature of political journalism has changed, and social media magnifies any tiny misstep and overwhelms the bigger body of ideas or opinions or thoughts that a candidate has. He felt it would not work in the age of Twitter.

The pick of Palin, fellow maverick

BALZ: I think you could certainly draw a line from Sarah Palin to Donald Trump. He picked Palin as vice presidential nominee because they were desperate. They needed to shake up the race. And to be fair, I think McCain didn’t know her well but nonetheless saw something in her of himself. Which is to say, a maverick politician who was willing to take on the political establishment, which she did in Alaska when she ran for governor.

And some of the policies that she pursued went against embedded interests. And in addition, she was a woman. All of that added up to a choice that would change perceptions of the race at a time when he desperately needed that to happen. But did his picking her lead to Trump? I don’t know. I’m not sure I would credit, or whatever, him for bringing us into the Trump era. There was a political stirring in the country, and she took advantage of the platform he gave her.

DIONNE: McCain could be impulsive, he could be impatient, and I think that is one of the worst choices he made both for the country and for his own interests. But I think that also reflected the fact that even after he’d won the nomination, he still had not nailed down the right wing of his party and felt that that might do that. But it was a terrible mistake, and I suspect he regretted it.

The legacy of a leader

GERGEN: I do think he’s going to leave a leadership void, certainly from his generation. It’s so rare now to find anybody on Capitol Hill who will stand up as firmly as he has for what he thinks is right as opposed to what is politically convenient. I think the attacks on him by [Steve] Bannon and Trump only enlarged his reputation because he stood up to them. He’s a devout conservative, but there were a lot of liberal people standing up and saying “Thank God for John McCain.”

I think he wants to go out with all flags flying. I think he’s determined to leave a mark. He’s not trying to get people to salute him or to romanticize him. Patriotism, to him, extends way beyond party. It has much more to do with country. He’s one of the few people who still believes that. I think that he’s had the most impact upon our sense of honor. In his public life, he has taken the honorable road again and again, and people admire him for that.

DIONNE: I don’t think there will be anybody else like McCain. He will be remembered — some will honor him, and some will disagree with him — for his consistent hawkish foreign policy. That has been a through line of his career, that’s what he believes in, and that has been unchanging. He will be remembered as a reformer, and while the Supreme Court gutted McCain-Feingold, I don’t think we are finished with political reform. I think that when people look at the Trump years, they’ll see McCain as one of the very few in his party who was willing to take on Trump. Some of us wish he had voted against the Trump initiatives even more often. But nonetheless he was willing to be one of two, three, four Republicans in the Senate to really say, “There’s something wrong here,” and I think he’ll always be remembered for that.

And I think he’ll be remembered, like Ted Kennedy, as representing an earlier time when party divisions did not lead people to an utter disrespect for the other side — not just “regular order,” but basic decency for the people you disagree with.

These interviews have been edited for clarity and length.