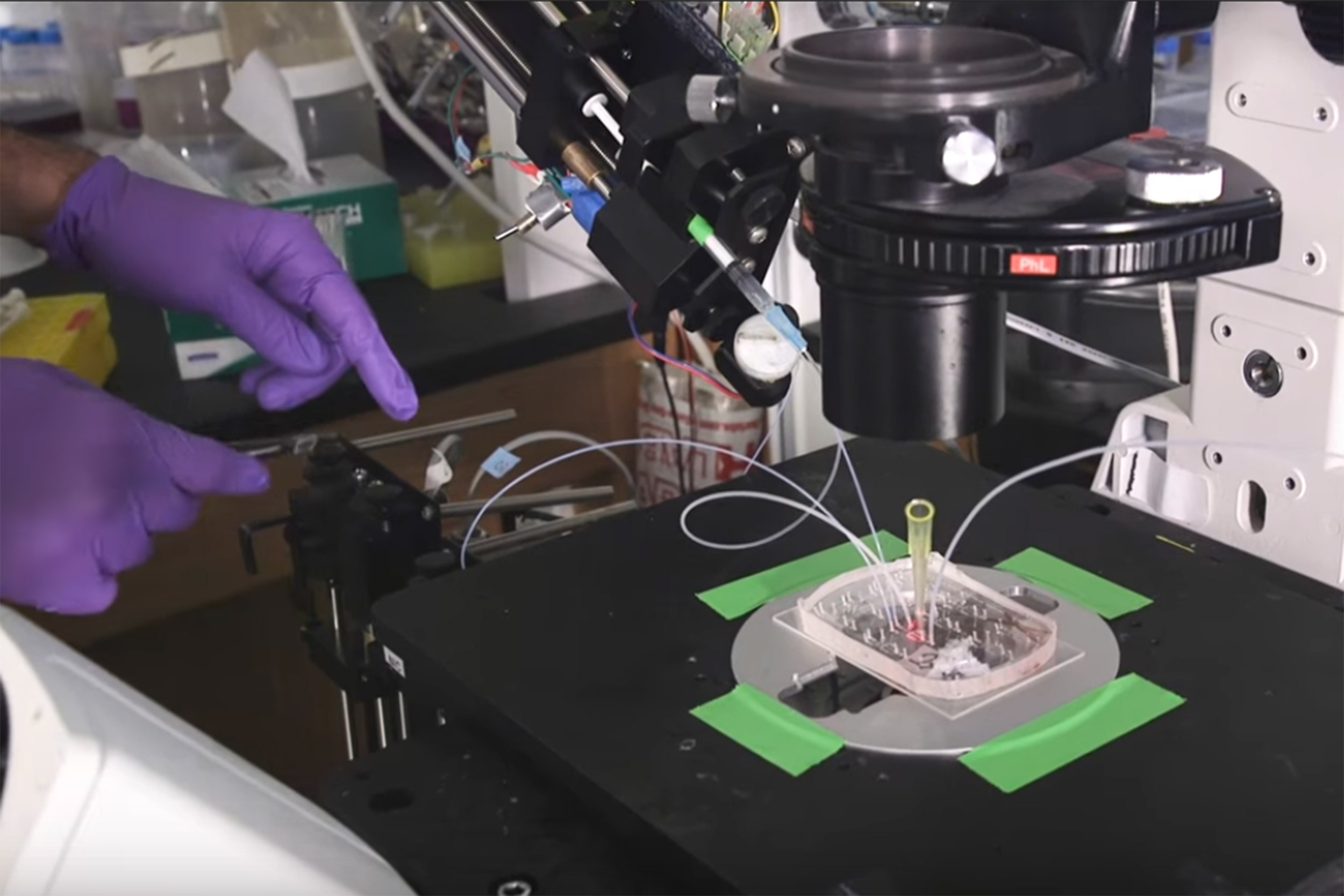

Surprisingly generous federal budget allocations are enabling Harvard scientists to push toward fresh discoveries, such as Medical School Assistant Professor Allon Klein’s device to analyze single cells.

Video still courtesy of HMS

From federal support, groundbreaking research

Latest budget allocations allow Harvard scientists to push toward fresh discoveries

For Allon Klein, federal scientific research funding allowed him to build a microscale device to analyze single cells affected by disease, adding new precision to understanding how cancer causes things to go wrong in the human body.

For Shelly Greenfield, federal dollars meant being able to investigate and develop a new substance-use-disorder treatment program, filling a gap in women’s care amid a spreading opioid epidemic.

For Conor Walsh, government financial support meant being able to assemble large, interdisciplinary teams to develop soft, wearable robotics that can help those disabled by stroke and other conditions, and even boost the abilities of healthy people — such as soldiers — who work under challenging conditions.

The research of those and thousands of other investigators at institutions across the United States represents a rare spending priority valued by lawmakers of both parties, according to the chairman of a key House subcommittee. That’s why, when statutory spending caps were eased earlier this year, lawmakers looked to boost the bottom line for agencies that finance research into human health, engineering, energy, and other areas.

“In an era where we’re very divided, it’s nice to find an area where people will really work hard to see what we can do to make an investment here, [and ponder] what tough choices do we have to make elsewhere in the budget,” said U.S. Rep. Tom Cole, R-Okla., who chairs the House Appropriations Committee’s subcommittee that oversees the budget of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), a major source of funds for life science and medical research. “It’s something that Democrats and Republicans like to work on together.”

In the most recent budget process, Cole worked closely with his congressional counterpart, Sen. Roy Blunt, R-Mo., who chairs the Senate Appropriations subcommittee that oversees the NIH budget, to include a $3 billion, 8.8 percent increase for the agency. The hike is the third multibillion-dollar increase in as many years for the NIH, as Congress works to return the agency to funding levels not achieved since 2003. At that time, Congress had just completed a historic doubling of the NIH budget, but years of stagnating funding eroded purchasing power because of inflation.

“This was a pleasant surprise, actually shocking,” said Sarah Axelrod, assistant vice president and head of Harvard’s Office for Sponsored Programs (OSP), which oversees Harvard’s external research funding from both private and public sources. “That [NIH increase] for us is great news, considering 68 percent of our [research] money is coming from the NIH.”

The federal budget approved by Congress and signed by President Trump in March also includes increases for other agencies that fund university research, with the Defense Department getting additions of 7.3 percent for applied research, 4.7 percent for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), and 2.9 percent for basic research. The National Science Foundation (NSF) received 4 percent more, while NASA’s science budget rose 7.9 percent, and the Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy (ARPA-E), which funds high-risk, high-reward energy projects, received a 15.5 percent increase.

“The increase in federal research funds in this year’s budget is a welcome sign that the vital partnership between universities and the federal government is strong,” said Harvard President Drew Faust. “It is gratifying to see that Congress shares our conviction that federally funded research benefits the public in manifold ways. It drives economic growth as new inventions and discoveries are brought to market, improves health and well-being through advances in diagnostics and treatment, and opens new avenues of achievement by expanding knowledge and sparking discovery. No collaboration holds more promise for the people of this country.”

“It’s not just that the quality of the science is good, but the environment and the culture of the science here is really intoxicating. There’s such a strong spirit of collaboration; it’s such a can-do attitude. It really is the American spirit embodied in the scientific enterprise.”

Allon Klein, researcher and assistant professor of systems biology, Harvard Medical School

At Harvard, external research funding provides critical support for the University’s scientific enterprise, totaling about 18 percent of the University’s annual operating budget. Axelrod said that reliance on outside research money varies widely from School to School. Harvard Business School, for example, accepts no external funding, while outside support for faculty research makes up 68 percent of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s budget.

“It’s a huge range,” Axelrod said.

Last year, Harvard’s Office for Sponsored Programs tallied 3,388 active awards for Harvard faculty members, of which 58 percent were federal and 42 percent were from private sources. The federal grants tend to be larger, Axelrod said, resulting in federal research support significantly outstripping that from other sources, $613 million versus $255 million.

Harvard’s share of federal research dollars peaked at $639 million in 2013, the last year of an Obama-administration stimulus program designed to buoy the economy in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. Funding subsequently declined or remained stagnant, followed by gradual increases over the past three years, Axelrod said. Even with those increases, however, Harvard’s federal research funding in 2017 remained below that 2013 peak, at $613 million.

Cole said Congress has generally looked at funding for the NIH and other research agencies more kindly than presidential administrations have, whether Republican or Democratic. Discussing his own motivation, Cole said he recognizes the potential of medical research to ease human suffering and also sees compelling economic reasons to support the nation’s robust scientific enterprise.

Not only does scientific research result in new technology, inventions, and devices that spark the economy — for example, 57 percent of drugs patented in the world are patented in this country, he said — medical advances can also reduce costs of care.

That’s critical in the case of ailments such as Alzheimer’s disease, which will become more prevalent in an aging nation, exacting both a rising human toll and skyrocketing medical costs.

“It’s a terrible disease, and I’m familiar with it — my dad had it — but it also costs us $259 billion a year in Medicaid,” Cole said. “It will literally bust the federal budget if we don’t figure out a way to at least slow the onset. If we can slow the onset for five years, it will cost 42 percent less.”

“Increases in the NIH budget are absolutely critical for opioid use disorders, substance use disorders, and mental health disorders,” says Shelly Greenfield.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer.

Cole said he and Blunt had struck a deal on NIH funding to boost the agency’s revenue significantly, and, in the final flurry of negotiations that increased the overall budget’s bottom line, were able to add even more.

“We’d already made all the tough decisions we had to make, so the extra money allows you to go back and ‘plus up’ some of the areas you thought were important, and NIH is one we felt strongly about,” Cole said. “I thought we could do better than $2 billion; it turned out to be a lot better.”

Cole said the NIH’s $3 billion increase is likely to be “a one-time deal,” however, and the budget for fiscal 2019, which starts on Oct. 1, will likely be tighter. Still, Cole said, the goal is to provide the NIH with steady annual increases above the rate of inflation.

“We’re at a very interesting time for science right now, with precision medicine, initiatives on the brain,” Cole said. “We’re going to be able to do some spectacular things if we make the investments now.”

Harvard researchers share the vision of steady funding to enable breakthrough research that moves from the lab to the clinic, where it can help patients.

Shelly Greenfield, the Kristine M. Trustey Endowed Chair in Psychiatry and chief academic officer at McLean Hospital, and professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School (HMS), said much of her research into substance-use disorder and treatment over the years has come from two NIH institutes: the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

Research conducted under a NIDA grant, Greenfield said, led to development of a group treatment for women with substance-use disorders, which filled “a much needed treatment gap.”

Federal dollars, Greenfield said, support the basic science that helps people to understand how drugs such as opioids affect the body, to identify targets in the brain for new therapeutic drugs, to devise innovative treatments, and to test delivery to ensure that those can reach patients.

“NIDA and other institutes fund incredibly important research that is basic, translational, clinical, and implementation science, all of which are tremendously important in improving the delivery of effective treatments to patients,” Greenfield said. “Increases in the NIH budget are absolutely critical for opioid use disorders, substance use disorders, and mental health disorders.”

Greenfield said that continued increases are important not only to support new efforts to curb existing problems like opioids, but also to head off areas of emerging concern, like the possible resurgence of methamphetamine use.

At Harvard’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Conor Walsh, the John L. Loeb Associate Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences, is conducting research on soft robotics with the aim of designing assistive devices that can be worn like clothing and boost the capabilities of healthy individuals or help those afflicted by disease more easily carry on their daily lives.

“Larger budgets enable more diverse types of research projects and more interdisciplinary research projects that are critical to making some of the next breakthroughs,” Conor Walsh said.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Our work is very translation-focused, usually strongly motivated by a clinical need or a significant opportunity we’ve identified, and where we think bringing new disruptive robotic technology can make a difference,” Walsh said.

Walsh, who has received funding from the NIH, NSF, DARPA, and the Office of Naval Research, said the additional dollars are good news for large interdisciplinary projects like those he leads, because the grants have to support investigators from different disciplines, including engineering, materials science, and physical therapy or movement science.

“Larger budgets enable more diverse types of research projects and more interdisciplinary research projects that are critical to making some of the next breakthroughs,” Walsh said. “We have big teams supported on these projects.”

Walsh and Cole agreed that also important are the signals that funding sends to a new generation of researchers. Tight federal budgets mean fewer projects can get funded, which can influence junior scientists who are evaluating their career paths to think their future may be rosier elsewhere.

“If somebody is just deciding to choose a career path in academia, one thing to think about is what the funding landscape looks like, and are they going to have realistic chances and good opportunities to get funding,” Walsh said. “It’s showing that the country is supportive.”

Allon Klein, assistant professor of systems biology at HMS, said federal funding is part of what sets this nation apart from others. Klein, who was raised in Israel and received bachelor’s and doctorate degrees from Cambridge University, came to HMS for a postdoctoral fellowship and became so enamored by the science scene that he decided to stay.

“The money is being spent right at the place where value is being created,” Allon Klein said. “It’s essentially funding … completely new concepts which will empower the next generation of drugs or cures of disease. I think as far as the government is concerned, this is money very well spent.”

Video still courtesy of HMS

“My immediate impression … is the science here is absolutely electrifying. It’s not just that the quality of the science is good, but the environment and the culture of the science here is really intoxicating,” Klein said. “There’s such a strong spirit of collaboration; it’s such a can-do attitude. It really is the American spirit embodied in the scientific enterprise.”

Klein has developed a device to analyze single cells. By doing that in large numbers, researchers can understand with more precision what is going on in disease states. In cancer studies, for example, tumors are typically ground up and analyzed in bulk, providing an averaged view of what’s going on inside. But tumors don’t work as a single cellular mass, Klein said. Instead, the cancerous cells are fed by blood vessels, and the mass influences the immune system to shut off the body’s defensive response. By studying those cells individually, Klein said, researchers will have a better idea of what’s going on and where to intervene.

“It’s rare that a disease only affects a single cell type, and a good example of that is cancer, where inside a tumor there is much more than just the cells themselves of the cancer. They would not be able to survive without being fed from blood vessels. They’re able to co-opt blood vessels from surroundings. They take advantage of our immune system,” Klein said.

The device he developed, with the help of an NIH pilot grant, has been licensed to private industry, thereby potentially not just helping patients but also creating private jobs. Klein and Greenfield see research funding as one of the government’s best investments.

“The money is being spent right at the place where value is being created,” Klein said. “It’s essentially funding not how to make [an existing] product better, but rather [funding] completely new concepts which will empower the next generation of drugs, or cures of disease. I think as far as the government is concerned, this is money very well spent.”