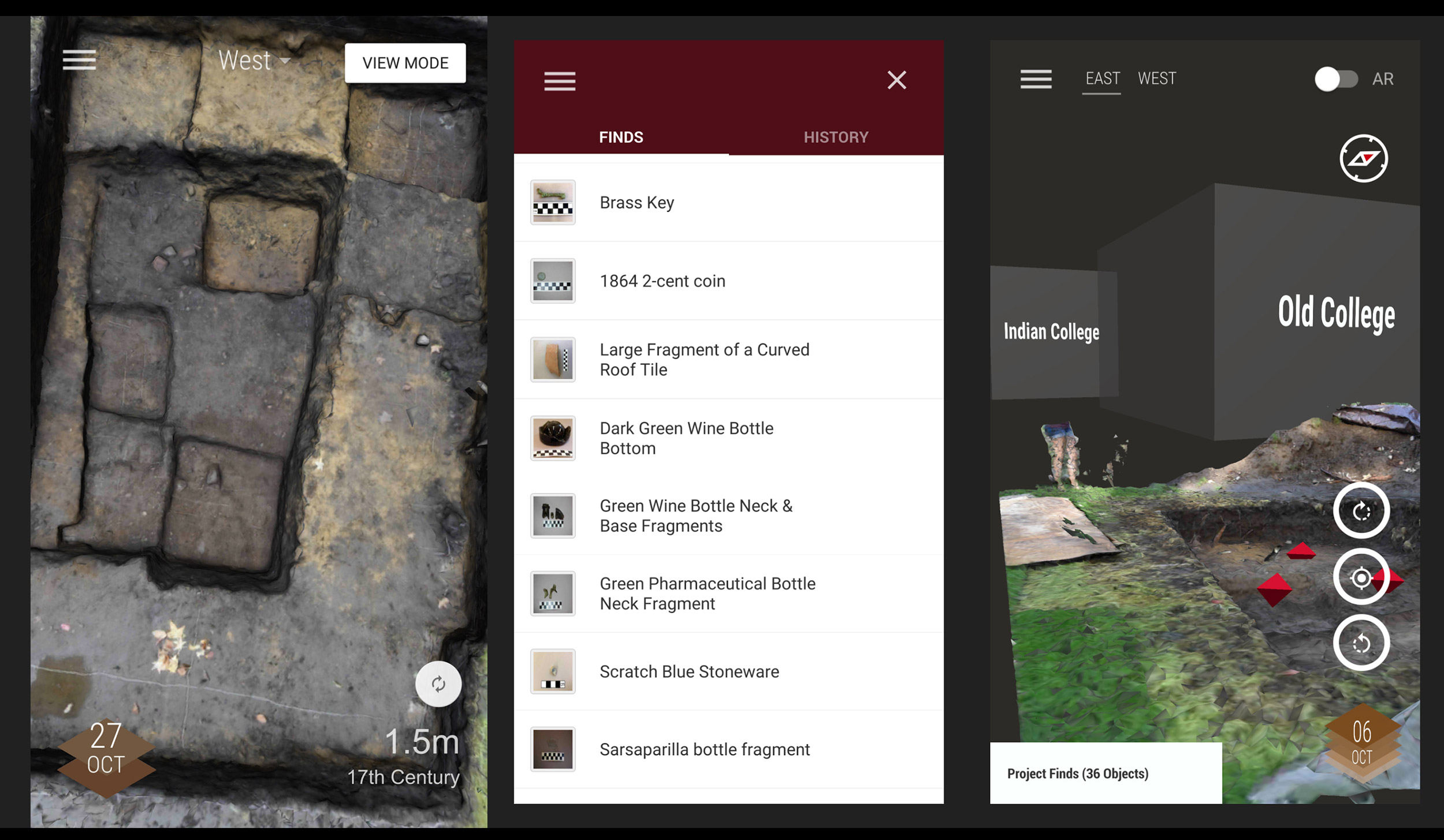

Harvard student Alexis Hartford tests the Harvard Yard Archaeology Project app. The app will let users “see” where various objects were discovered during Yard excavations.

Photo by Jeffrey P. Emanuel

In Yard digs, there’s an app for that

Come next fall, web link will allow viewers to probe archaeological finds from Harvard’s earliest days

The trenches have been hard to miss. Dug nearly every other year since 2005 between the trees and pathways crossing venerable Harvard Yard, these excavations have begun to offer insight into its history. Next September, when work begins again, visitors will have a new tool with which to peek into the past: an augmented-reality app that will re-create these excavations and shed light on some of their more interesting finds.

A collaboration among Harvard’s Peabody Museum, Cambridge startup Archimedes Digital, and the digital scholarship support group made up of representatives from academic technology, the Harvard Library, and the History Department, the app — simply called the Harvard Yard Archaeology Project, for now — will make its public debut next fall.

Because the dig will resume again as the fall fieldwork for the Archaeology 1130, “The Archaeology of Harvard Yard,” the timing will allow insight into an ongoing project, along with a deeper understanding of the discoveries from digs in fall 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014, and 2016. The yearlong course focuses on lab work involving the finds during the ensuing spring semester.

Although each year’s excavation site moves slightly within the Yard, the app will provide access to previous years’ work. With GPS to guide users to the precise location of each trench and 3-D overlays to virtually visualize what lay within, the app will let users “see” where various objects were discovered, complete with information about the strata of the dig where the object was found, and its importance.

“You have the exact experience of being there when the trenches were opened, but the objects are clean, their biographies are written, and you’re not going to fall in,” said Jeff Emanuel, associate director of academic technology, who oversees the app project. (Because Emanuel is also an archaeologist — specifically a CHS Fellow in Aegean archaeology and prehistory — he added, “I also have a vested interest in this one.”)

The app, now in its beta or testing mode, will give users access to the object biographies of select pieces, along with essays and maps that trace the likely history of objects, as well as their social or cultural meaning. These range from tobacco pipes and wine bottles — there was “an unbelievable amount of smoking and drinking on campus,” said Peabody Museum curator Diana Loren, one of the course’s instructors — to bits of type. Sourced from the first printing press in the British colonies, Loren (who shares teaching duties with co-curator Patricia Capone) said the type “was used to print religious texts in the Algonquin language to facilitate conversion” of those Native Americans.

Those finds were discovered around the remains of the Old College building, the first university building in what became the United States, which dates from 1639, and the Indian College, which boasted Harvard’s first brick building, from 1655. (The Indian College was established in 1650 to house and educate Native American students so they might, in turn, proselytize Christianity.)

Since 2008, “Digging Veritas,” an exhibit at the Peabody Museum, has been introducing viewers to many of these newfound treasures. With the app, all that information will be immediately available and, perhaps most noteworthy, accessible at the very sites where the discoveries were made.

Loren sees the technology as keeping the archaeological experience alive. “After we leave the Yard, you don’t know what we’ve done,” she said. “It’s beautiful, thanks to Harvard’s landscape services. This kind of allows you to understand the process of excavation when excavation is not taking place.”

Overall, the app should enlarge on the aims of the class, which Loren describes as, at least in part, “to provide a better sense of the multicultural institution, its goals in the early colony, and to have a place for that history to be remembered today.” In the students’ encounters with the real objects used by their predecessors, she said, they “have this visceral experience. These are students digging the past lives of students. They understand the history in a whole other way.”

The project app, she hopes, will further the mission “to make that history known and to share it.”

The public can experience an augmented reality “excavation” with the app, guided by Harvard graduate student Alexis Hartford, during the Amazing Archaeology Fair at Harvard on March 24.