In his new book, “Vanishing Bone,” Harvard surgeon William Harris describes the setbacks on the path to a breakthrough collaboration that corrected a major problem in hip replacement surgery.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Hip replacement needed a ‘light bulb moment.’ Getting there was painful.

Harvard surgeon’s new book describes setbacks before breakthrough MIT collaboration

In 1957, British orthopedic surgeon John Charnley saw what William Harris today calls “the promised land.”

That glimpse was the first total hip replacement, an operation that almost miraculously restored pain-free movement and active lives to patients whose hip-joint damage, often rooted in arthritis, had made even the simple act of walking across the room difficult.

Empowered by advances in materials, Charnley dispensed with the surgical half-measures of the past, removed the damaged joint entirely, and started over, replacing the cuplike hip socket with one made of Teflon, known for its slipperiness. He cut off the top of the thighbone and inserted the end of a rodlike metal implant into its center, cementing it in place. The round head of the implant — like the natural one at the top of the thighbone — fit into the Teflon hip socket.

The procedure seemed to work, but not for long. Within a year, complications arose. The routine movement of the balls in the sockets made the Teflon wear too quickly, loosening the implants. Charnley was forced to reoperate on nearly 300 patients after they developed what he described as an infection around the implant.

“The shining side of that unmitigated disaster was that he had seen the promised land,” said Harris, who was 27 when Charnley performed the first operation. “These people were so good [after the operation]. He said, ‘What we need is a better plastic.’”

Charnley filled that need with a more-resistant material called high-density polyethylene, which he began using in a new version of the artificial hip joint in 1962. Years passed, then a decade, with no sign of the accelerated wear that had doomed the Teflon socket.

By 1974, Harris was a noted orthopedic surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital and clinical professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School. One day he saw a California lawyer, referred by doctors in San Francisco, who had undergone hip replacement surgery seven years earlier. The procedure had initially brought pain relief and renewed freedom of movement. But the hip pain had returned.

Harris was startled when he looked at his new patient’s X-rays. Large portions of his thighbone had been eaten away. Cancer was the only thing Harris could think of that destroyed bone like that, but it also seemed unlikely. First, cancer had never been associated with hip replacement. And second, bone cancer wasn’t typically found in the femurs of 55-year-old men.

Further tests brought good news, confirming that the patient was cancer-free. But those results were tempered by the fact that his doctor remained stumped.

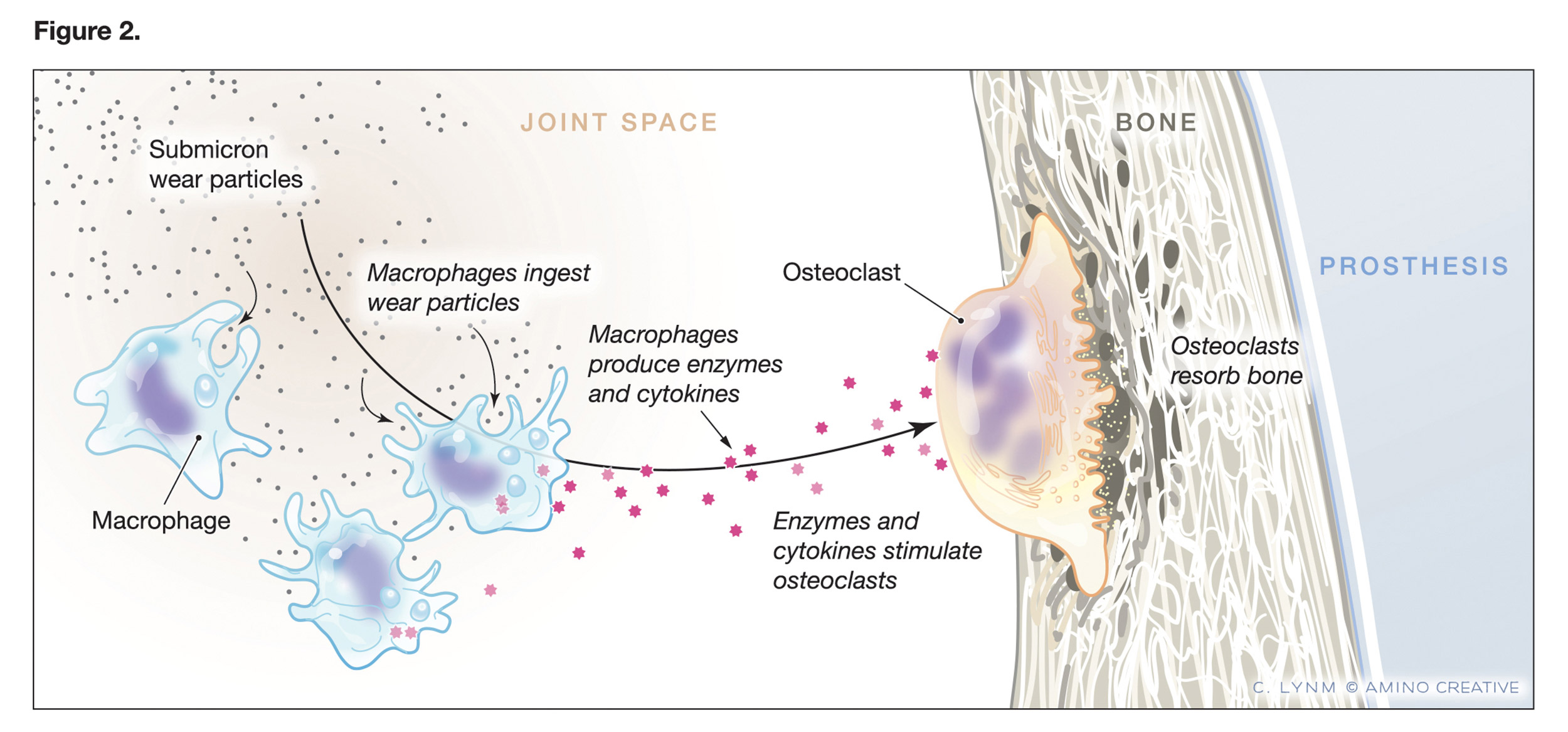

Figure depicting the role of submicron wear (debris) particles.

Credit: © Cassio Lynm/Amino Creative

Harris himself would see three similar cases that year and many more in the years to come. In time, the condition became so widespread — reaching over a million cases — that it was defined as a new disease, periprosthetic osteolysis.

The condition led not just to implant failures, but also to hip fractures, femur fractures, and complex reoperations to install new implants. It would take decades to devise a solution, in the form of a new material — highly crosslinked polyethylene — pioneered in the labs of Harris and his Massachusetts Institute of Technology collaborator, biomedical engineer Edward Merrill.

“In my clinical office, I often have the privilege of seeing one happy postoperative patient after another,” Harris, now the Alan Gerry Clinical Professor of Orthopedic Surgery Emeritus, writes in his new book, “Vanishing Bone: Conquering a Stealth Disease Caused by Total Hip Replacements.”

“It was one of the real pleasures of my work as a surgeon, to put an end to the deep, daily grief that patients often suffered by giving them total hip replacements. Their joy and gratitude afterwards was one of my greatest rewards. However, those with bone destruction were my worst nightmares.”

As the book details, the journey of Harris, his patients, and multiple collaborators included promising leads and roads to nowhere, the development of a new hip simulation machine, at least one lab explosion, and too much time in a patent case. The adventure ultimately led to a new generation of hip implants and, possibly, the breakthrough that Charnley had glimpsed more than 60 years earlier.

A few years after Harris first described the condition, in 1976, a separate research effort traced its cause to tiny particles of the cement that secured the metal thigh implant inside the femur. Those particles caused a massive immune reaction that in turn triggered osteoclasts, the only cell in the body capable of destroying bone.

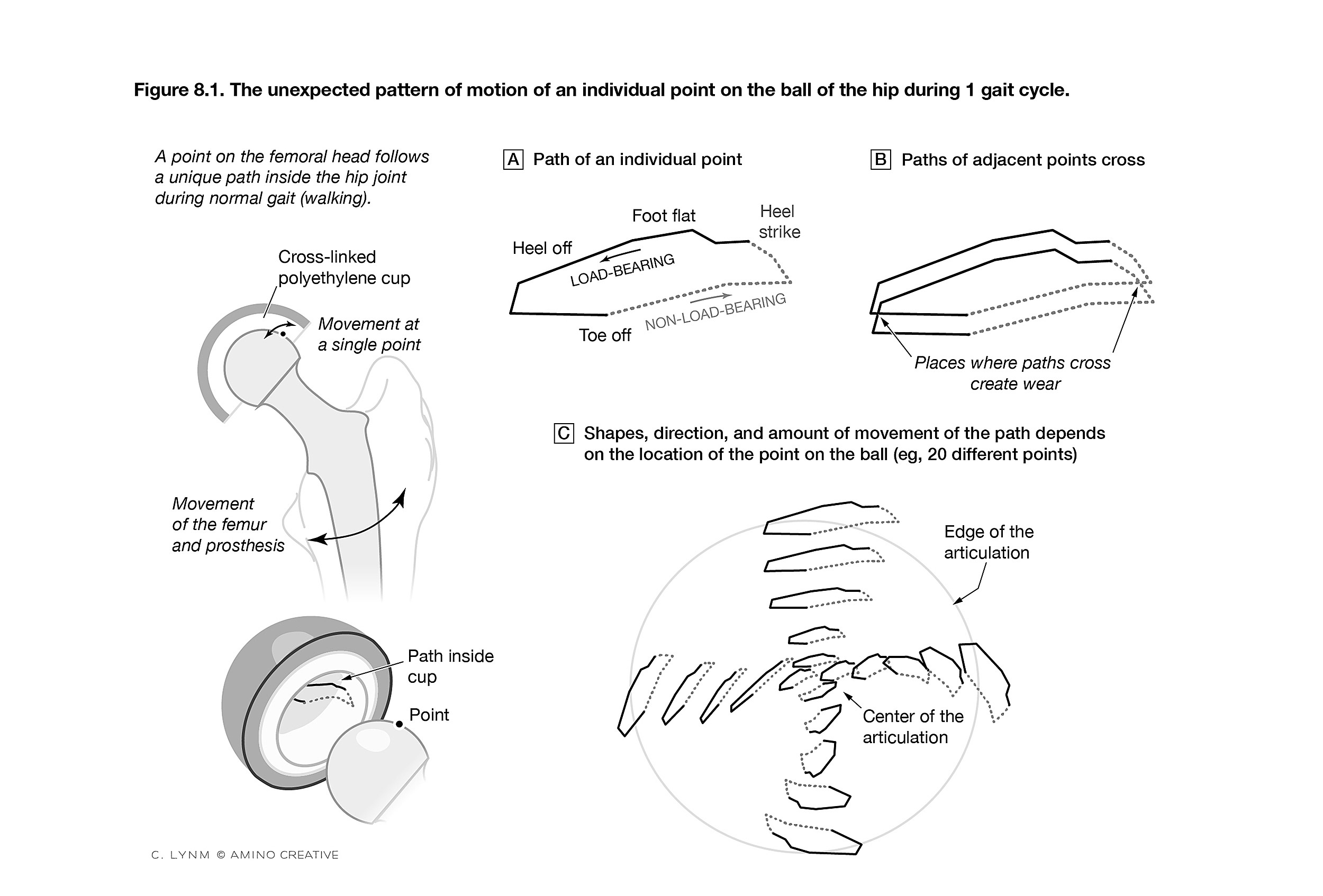

Figure depicting pattern of motion of points on the ball of the hip during gait 1 cycle.

Credit: © Cassio Lynm/Amino Creative

The discovery led to the condition being called “cement disease,” prompting the development in the early 1980s of porous-metal implants that allowed the bone to grow into the implant and hold it in place in the thighbone.

But Harris was still seeing new cases in 1990, even among patients with cement-less implants. Further research showed that particles were still present, but of the polyethylene that made up the hip socket. Though the polyethylene was far more durable than Teflon, the regular motion of the ball in the socket still caused wear, producing particles that set off the same destructive immune reaction.

With that discovery, researchers finally understood what was happening in the body. It was not a cement disease, but a particle disease. With so many hip replacement surgeries continuing around the world, what was needed was a material even more durable than polyethylene.

The new answer came from studying the old one. Harris had asked patients to donate implants for study after they died, and he worked with lab members to examine them under a scanning electron microscope. The researchers noticed something interesting: The long, skinny molecules of high-density polyethylene, which normally curl haphazardly like spaghetti in a bowl, as Harris described it, had become aligned in the direction of the back-and-forth motion of the joint.

The surgeon wondered whether the team was seeing wear’s signature and whether, if they connected the individual molecules to keep them in their original configuration, they could halt the damage.

“That was a light-bulb moment: ‘Wow, I wonder if in fact that realignment is critical to the particular type of wear that leads to the tiny particles?’” Harris said.

Harris knew MIT’s Merrill, a polymer scientist and noted pioneer in biomedical engineering, and asked him if it could be done. Merrill said it could, by irradiating the polyethylene into a new form: highly crosslinked polyethylene.

The idea worked. In 1998, the first artificial hips using highly crosslinked polyethylene were put in patients. Since then, across roughly 7 million cases worldwide, “there’s not been one documented reoperation caused by the bone destruction, which used to be so common,” Harris said. “That is huge progress.”