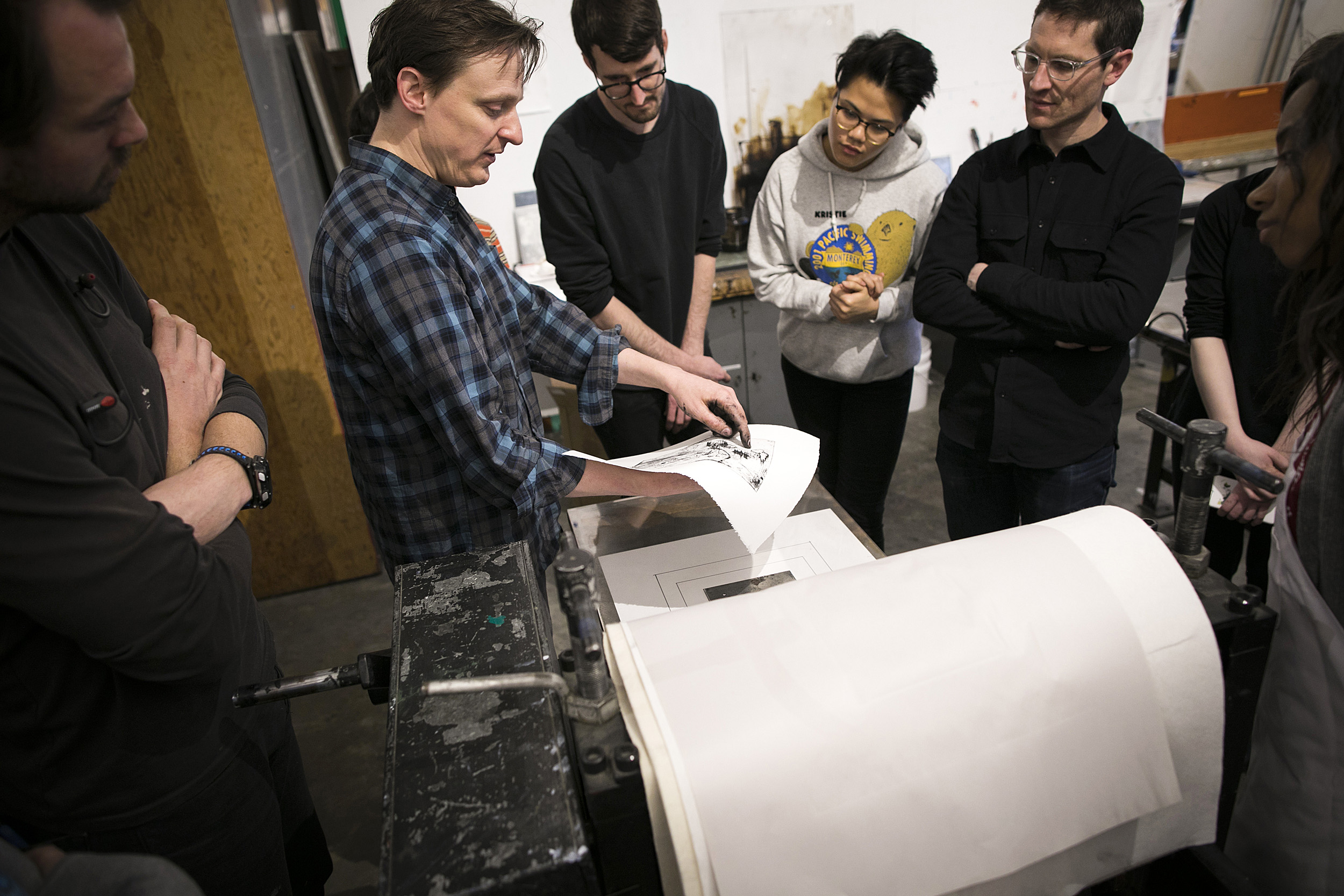

Graduate student Rachel Vogel tries her hand at printmaking.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Studying art by making it

Class encourages students to create works to better understand the finished product

Historically, Harvard has valued the head over the hand, but that may soon shift — at least in one discipline.

Under the auspices of Jennifer L. Roberts, the Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities, and Ethan Lasser, Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. Curator of American art at the Harvard Art Museums, graduate students, particularly those in art history, are joining a University movement against what Roberts calls a “longstanding, multi-century bias toward conceptual and mathematical, verbal, abstract forms of knowledge over the forms of knowledge embedded in making.”

As their class “Minding Making: Art History and Artisanal Intelligence” goes through its second iteration, students are learning how hands-on experience with materials and processes feeds a different kind of awareness and a new appreciation of the finished product.

Part of a larger project, detailed at mindingmaking.org, the class follows several summer graduate workshops, as well as a broader trend toward recognizing art-making as part of the University’s “cognitive life,” said Roberts. “The humanities are in the middle of what’s known as the material turn,” she explained. “There’s a lot of interest in matter and materiality, but that hasn’t really yet translated into a clear new way of thinking about making, about interacting with all that material.”

“Maker is a generic term that would encompass both the ceramicist and the person soldering together a circuit. We wanted a term that moves beyond studio art-making or craft artisanship.”

Professor Jennifer Roberts, pictured below with Ethan Lasser

This course seeks to address this tactical way of thinking, with readings on the intellectual history of crafts, as well as visits to artists, artisans, and their workplaces, including an aluminum casting factory.

“Maker,” Roberts explained, is a “generic term that would encompass both the ceramicist and the person soldering together a circuit. We wanted a term that moves beyond studio art-making or craft artisanship. Art historians tend not to go to factories. They’re not interested in mass production. There are a lot of assumptions about what someone does.”

“Art history,” added Lasser, “is constructed around a finished object, and the power of this approach is in going back through it and understanding what it takes to get to that object.”

In Roberts’ words, the practitioners seek to “get outside the library and books for sources of knowledge.” Lasser elaborated, explaining that the goal of the course is to provide “a sense of the feel, the tactile knowledge, of how much physical labor goes into something.”

“At every stage,” he said, “there’s some information that art historians don’t generally write about because they don’t know about, because they’re just looking at the finished object.”

Destiny Crowley and Ashley Gonik engage in the painstaking process of preparing plates.

On a stormy Friday, students were involved in another element of the course, trying their hands at etching: from the first preparation of the plates through printing. The work is laborious, and students such as Destiny Crowley of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences were spending considerable time applying the thick black ink and then wiping it nearly off before attempting to print a first proof.

Speaking while she worked, Crowley, a first-year student in the history of art and architecture Ph.D. program, explained that she signed on to address “a gaping lack in my education when it came to the actual creation of art.” As she wiped the viscous ink over her plate, she noted how that also gave her additional insight into works she has long admired: the Blank Signs series of prints by artist Ed Ruscha, who hails from her home state of Oklahoma.

“The aquatint gives the print a very light shade of coloring,” Crowley explained, describing Ruscha’s series. “And the signs themselves are left stark white.” Noting “the juxtaposition of moving from darkness to light, the pitch black of the ink, the deep blackish brown of the asphaltum ground that we had to apply to the plate,” she said, “I find it very interesting that the print ended up being such a bold interplay of lightness.”

Working with the coal-black ink, she shared her insight. “It is really amazing how you can go from a really onyx black — almost a void on this space — and strip that away,” she said. “There’s a reason why artists choose the artistic processes they do, an etching versus an oil painting.”

Drying and drawing. Kristie La and Leah-Justin-Jinich.

“There are so many different reasons for choosing a material,” agreed Iain Gordon, who is pursuing a master’s in design studies. Unlike several of his classmates, Gordon, who was drying a treated plate, has been involved on the “making” side, building furniture as well as other projects for several years. “For me, this is a way to engage with the making in a theoretical and critical way,” he said.

“I knew it would be time-consuming and unpredictable and a different kind of mental and physical energy,” said Rachel Vogel, who is in her second year of the Ph.D. program in the history of art and architecture. “But you don’t realize the extent of all of those things until you really start doing it.

“Learning those kinds of chains of causality and being able to recognize how a particular choice an artist made might be a response to something else that’s happening in the print …” She paused as she continued to wipe ink off her etching plate. “To begin to unpack the layers that must have happened in order for the artist to have constructed a plate is something that really can only happen once you’ve had the experience of making prints yourself.”