“I’m a Dylan professor and a Dylan fan,” says Harvard Professor Richard Thomas, who teaches a popular freshman seminar on the singer-songwriter and recently published “Why Dylan Matters.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Parsing the poet, Bob Dylan

New book examines the influence of the classics on the Nobelist’s music

Classics professor Richard Thomas discusses “Why Dylan Matters” with Robin Kelsey

Richard Thomas may be the first Harvard professor to celebrate a book release that’s co-sponsored by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. But that’s where the classics professor and Dylanologist found himself last month for the publication of “Why Bob Dylan Matters.”

The book was sparked by Dylan’s 2016 Nobel Prize in literature, but grew from Thomas’ popular freshman seminar “Bob Dylan,” which he has taught every four years since 2004. The course, affectionately known on campus as Bob Dylan 101, studies the music and the influence of the likes of ancient poets Virgil and Homer on the American singer-songwriter.

The George Martin Lane Professor of the Classics has seen Dylan perform scores of times, and considers “Why Bob Dylan Matters” only the first verse of many to come about the present-day bard.

GAZETTE: Did you write this book as a classics professor teaching a class or as a Dylan fan?

THOMAS: I’m a Dylan professor and a Dylan fan. I’m always a Dylan fan. The book wouldn’t have happened if Dylan hadn’t started entering into the world of my texts 20 years ago. He’s come to me in a way, and I’ve always been with him. The book is also about how he related to Roman poets really from the beginning, but those resemblances are accidental, just reflections of shared genius. But his more conscious adoptions are a more recent thing.

The book is recognition of what Dylan is. It came when he won the Nobel [last year]. I was contacted by a number of press and agents. I first thought, “No, I’ll think of doing a Dylan book further down the road.” I was about to teach three courses in the spring semester, and they wanted a draft by May 1. But I was persuaded by an editor at Harper Collins who wrote a very good and persuasive email. I was pretty terrified to begin with. But the terror-to-exhilaration ratio eventually shifted as I saw what I wanted to do. “Why Bob Dylan Matters” didn’t exactly write itself, but I was thinking of it every minute I wasn’t teaching. I wanted the book to put Dylan in a serious literary tradition that pushed back against the idea that he’s just a protest singer, that he’s ephemeral, that he won’t be around the way great literature stays around.

GAZETTE: You have taught “Bob Dylan” since 2004. Does it draw hardcore Dylan fans, casual ones, poets, or all three?

THOMAS: It’s all of that. In the applications that students submit, I’ve tried to select a bit from those different groups. Each year one to three know Dylan as well as I do, and there are those out there who know him better than I do. Then there are some whose parents listen to him, and they’re curious. Parents always come up in discussions. Last fall, one parent took his daughter to a show in the desert in Nevada to see the Rolling Stones, Neil Young, and Dylan. I’ve also gotten students who are songwriters who realize Dylan is without parallel, and are trying to learn or improve their craft. The course is not letter-graded, so they can take a chance, and I always advise students: Take a freshman seminar that interests you because you’ll make 11 new friends. We even have a marriage that started out in my class a few years back.

GAZETTE: You trace the influence of the classics on Dylan to his early years, even traveling to his hometown of Hibbing, Minn. What did you find there?

THOMAS: I found out about his involvement in the Latin Club in early 2000s when the camera in Martin Scorsese’s documentary film “No Direction Home” panned Dylan’s senior yearbook entry. It had three items: to join “Little Richard,” Social Studies Club, and Latin Club. And I found a clipping from the Hibbing Hi-Times about the induction of new students in the Latin Club. The year he was in the club was the year I started taking Latin as a 9-year-old in New Zealand. I’d already been hearing these lines from Virgil and later Ovid and Homer. There’s always been an intellectual and aesthetic and emotional component to the way I think about Dylan and his songs and career.

In his Nobel lecture, we heard him talk about books that were formative for him — Dickens, “Moby Dick,” “All Quiet on the Western Front,” and Homer’s “Odyssey.” As much as I’d like to think it was the joys of the Latin subjunctive and participles, I’m not sure how much Latin he’d done. One of the attractions was that it allowed him to go back into a world he’d inhabited in the movie theater, where he saw “The Robe” and other movies about ancient Rome. He’s about absorbing other times, other songs, and other traditions.

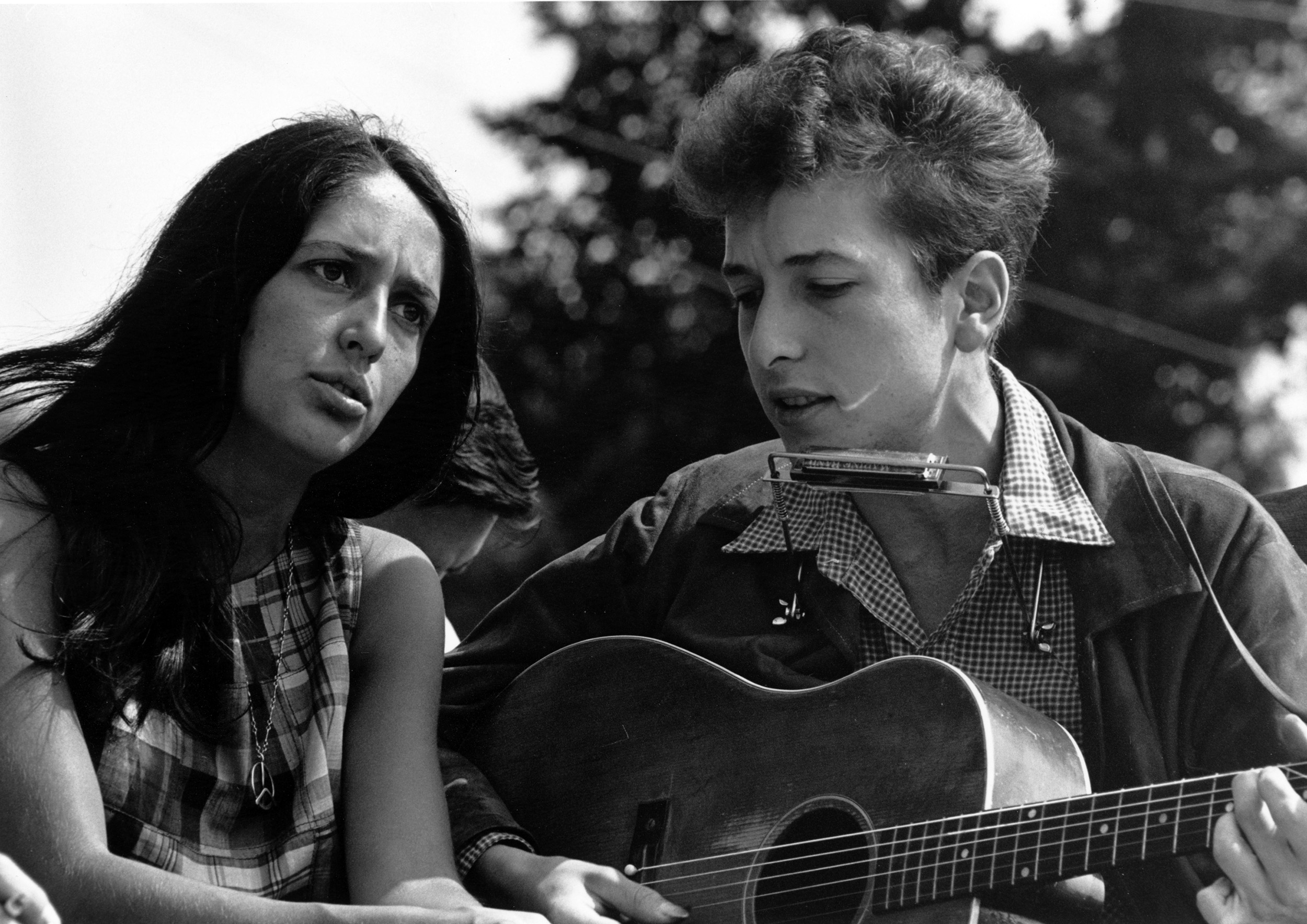

Folk singer Joan Baez with Dylan at the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C., Aug. 28, 1963.

Rowland Scherman/Wikimedia Commons

GAZETTE: You make the distinction in the book about “stealing” literary inspiration versus intertextualizing. Can you elaborate?

THOMAS: It’s similar to the way that Virgil can take, say, a simile from Homer. The setting of the Homeric reference is something Virgil brings into his poem. The Virgilian context becomes richer when discovering the Homeric layer. Dylan is identical, whether it’s Ovid or the folk tradition or T.S. Eliot in the song in “Desolation Row,” and Eliot also drew from Virgil and from Greek epigram in “The Waste Land.” Part of what we gain from reading Eliot or hearing Dylan comes from recognizing those prior contexts.

When Dylan has a line “No one can ever claim that I took up arms against you,” he is taking a line from Ovid, putting it in a song addressed to an ex-lover, perhaps. Seeing that new context, completely different from the source where it is taken, is part of the pleasure of hearing this song — along with the music, of course. That process with classic lyrics started with “Changing of the Guards” [in 1978], but really it’s 2001 when it became a central feature of his composition.

GAZETTE: How often have you seen him in concert?

THOMAS: I couldn’t afford to go see the Rolling Thunder Review in ’75 when I was in grad school. I didn’t see him until after I came to Harvard in 1977, and I’ve seen him pretty steadily across the years, probably 80 times. If he comes within a few hundred miles, I’ll go. The farthest I’ve traveled was to Texas. I talk periodically to his manager. He’s very helpful for us Dylanologists.

GAZETTE: You interviewed fans at a few concerts for the book. Were you surprised to find criticism for his song choices and musical arrangements?

THOMAS: He knows where he’s going. It often takes people a bit of time to catch up with what he’s doing. If you go to a concert and don’t hear the song version that you heard 20 or 30 years before so it doesn’t bring back your memory of whatever was happening to you back then, that can result in quite an emotional response, even anger that your memory has been disturbed. The general glowing mood of the other 2,000 people coming out of that show in Florida the month after the Nobel announcement was positive.

If you go to a Rolling Stones or Bruce Springsteen show, you’ll generally hear a pretty close version to what you heard when you bought the album. Dylan is not at all like that. He’s not only been producing new types of songs, new genres, much more literarily layered, but he’s also been singing the old songs with a band made up of five amazing musicians, completely in sync with the new styles he’s been teaching them. The set list on this tour has been quite predictable. It’s telling the story of his life. The arrangement of the songs, the way he’s peppered his own list with songs from the American Songbook — these so-called cover songs — these concerts are magnificent and utterly coherent.

GAZETTE: Are there more Dylan books to write? Is that what you will work on this spring when you are on leave?

THOMAS: The George Kaiser Family Foundation, on behalf of the University of Tulsa, bought Dylan’s archive, some 6,000 pieces, including song drafts. There’s the leather jacket he wore when he went electric, but more importantly, thousands of hours of recordings and archival drafts of this and that. I was able to see an early draft of “Tangled Up in Blue,” and the Bob Dylan Archive Center has just been opened to Dylan scholars. I plan to get out there. That’s a real trove.

This interview was edited and condensed.