Martin Luther, fallible reformer

Divinity School professor considers the man and his 95 Theses 500 years later

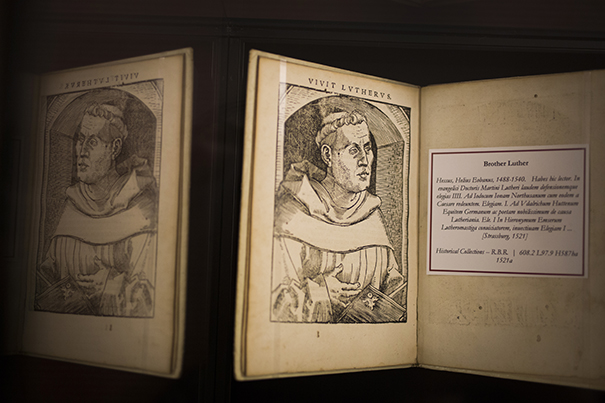

On Oct. 31, 1517, the German priest and professor of theology Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of a Wittenberg church, protesting all that he saw wrong with the late-Renaissance Roman Catholic power structure. Outraged by the church’s practice of selling indulgences to fund the reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, he challenged papal authority and church doctrine, eventually asserting the primacy of scripture and faith over priests and good works. Aided by the era’s most revolutionary innovation — the printing press — and protected by a sympathetic local prince, Luther sparked the massive religious upheaval that came to be known as the Protestant Reformation. We asked Harvard Divinity School Assistant Professor Michelle C. Sanchez about his life and legacy.

GAZETTE: What about Luther might surprise people?

SANCHEZ: One of my favorite aspects of Luther’s thinking is how he understands the devil. But it’s also underappreciated — no doubt because modern people don’t talk a lot about the devil. I find Luther’s interpretation of the devil to be insightful. For Luther, the devil doesn’t do his mischief by tempting human beings to bodily excess. It’s not sex or gluttony that we most need to fear. The devil works by tempting us to use our minds in ways that flatter us into thinking that we can find satisfaction, certainty, and happiness by mental domination, or by trying to think our way to mastery. But this only leads to more uncertainty, more fear, and most of all to melancholy. The devil operates this way because the devil is jealous of Jesus. Unlike the devil, Christ actually became human. So Christ can relate to human beings in a way that the devil can’t. The devil has to do his work by luring our minds away from the places where love and joy are found, and Christ is our most powerful helper precisely because Christ lived, ate, drank, and suffered right along with us.

GAZETTE: Did Luther cause the Protestant Reformation, or was the Reformation inevitable? In other words, had Luther not nailed his 95 Theses to the church door, would someone else have initiated a major split in the church?

SANCHEZ: It’s always tough to talk about historical developments in terms of inevitability, because social systems are vastly complicated and human actors are notoriously unpredictable. But it’s a fact that “reform” had been a common watchword in the church for at least two centuries before Luther, and many strategies of reform had been tried and tested before Luther’s 95 Theses appeared at All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg on Oct. 31, 1517.

Jan Hus was active in Prague in the early 1400s, drawing on ideas about an invisible church of the predestined in order to reimagine what the true church consisted of. He wanted to reimagine the church as a spiritual body in which true teaching and moral purity lined up, and to use this as a kind of Archimedean point from which to oppose what he saw as the obvious moral failings and greed of the church establishment at the time. Hus’ thinking was directly informed by his readings of Oxford scholar and dissident John Wycliffe, who had died in 1384 and shared many of the same concerns. Hus was ultimately burned at the stake at the Council of Constance in 1415, which is interesting in retrospect because the third stated purpose of the council was to “reform the corrupt morals of the church.”

So, in the two centuries prior to Luther, there was a general consensus that corruption was a problem and that reform needed to happen, yet there were radically different views on how to reform. The radicals began to appeal more strongly to biblical authority, but this was only one strategy alongside others. And when Luther came along a century later, he reinhabited many of these strategies.

GAZETTE: What were his key differences with the Roman Catholic Church?

SANCHEZ: Luther seems to have been driven, fundamentally, by his anxiety over whether and how you could know that you were, in fact, pleasing to God. Biographical accounts suggest that Luther never felt good enough, but he also never felt like he could make himself good enough by following the practices the church prescribed, such as confession and penance. So when he latched onto St. Paul’s claim that we are justified before God “by faith, not works,” this was deeply personal. It meant that God loves us not because we’ve achieved anything, but merely because God decided to love us. God decided to be “for us,” and proved it through the incarnation, when Jesus Christ was born as a human being to proclaim divine love, and to live and die on our behalf. So we’re assured that God loves us simply by believing God’s promise to love us, and this frees us up to follow Christ in acts of love to our neighbors and enemies.

Of course, this whole vision has another side — one that entails a passionate rebuttal of church practices designed to give one confidence before God. For Luther, the pursuit of righteousness is an asymptote: You can approach it, but you’ll never get there on your own. So when priests would preach, on the pope’s authority, that the purchase of an indulgence could remit a sin, Luther saw this as a fundamental deception misleading ordinary people away from the true source of salvation by faith.

GAZETTE: Others had protested church practices before, without making much of an impact. Why did Luther succeed where others had not?

SANCHEZ: This is where the question of historical inevitability gets complicated, because there are a lot of complicated reasons tying the Reformation to Luther rather than someone else. Some of these reasons are fundamentally political. Luther enjoyed the protection of his prince, Frederick the Wise, who was the elector of Saxony and a major political player in the Holy Roman Empire. So, unlike Wycliffe, Luther was operating closer to the center of ecclesial and political power; and unlike Hus, Luther did not meet an untimely death. These factors surely contributed to his success. Add to this the fact that Luther’s teachings proved friendly to German princes and the rising middle class, and you can begin to see why his reforms gained traction.

And there’s no doubt that Luther’s fame was aided by the economics of printing. Printers were cropping up all over German-speaking areas at the time, and Luther was really good at expressing himself in simple, everyday terms. So even though many ordinary people couldn’t read, Luther’s tracts — and the controversy they stirred up — proved to be really good for the bottom lines of printing entrepreneurs.

There’s also the fact that Luther’s way of understanding salvation — the emphasis he gave to faith in the promises of God — was really compelling, and downright inspiring to many, then and now.

GAZETTE: Can you summarize Luther’s legacy?

SANCHEZ: I find that Luther’s ongoing impact is most felt in the challenge his life poses to us; the way in which it’s both frustrating and inspiring, both embarrassing and revealing. Luther is a helpful conversation partner not because he’s some kind of reforming hero, but because he’s a mirror for our contradictions and struggles, for all the ways our society and our religious establishments continue to try and fail.

And yet, in some strange way, Luther remains important because he was wise to this very dynamic. He deeply got both the joy and the tragedy of the human condition. He didn’t try to explain away human flaws. He knew he was full of them. Instead, he called for us to learn to think of life in this world as a constant practice of critique, a constant practice of meeting the limitations of our own thinking. And he called on us to look for insight outside of ourselves, and especially in those places that seem most unlikely, most humble, because that’s where Jesus went. For Luther, we cannot forget that the highest form of divinity is revealed in the body of a criminal who was condemned by the state to death on a cross.

Interview was edited and condensed.