Harvard doctor recalls fall of Saigon

Bertram Zarins watched copters being pushed off his ship, and he operated on those fleeing mainland

In Bertram Zarins’ busy Boston practice, some patients recovering from surgery hop in on crutches. Others nursing aching knees or shoulders move gingerly as their names are called.

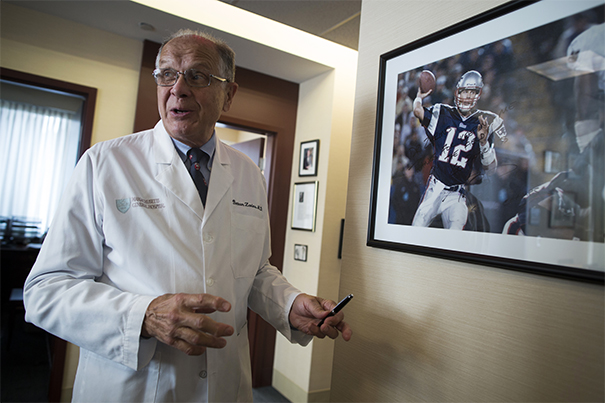

Down the hall, the walls of Zarins’ small exam room are covered with the kinds of photos that might be expected from an orthopedic surgeon and former longtime doctor for the New England Patriots, Boston Bruins, and New England Revolution. There are action shots of Drew Bledsoe, Teddy Bruschi, Taylor Twellman, Steve Grogan, and Bobby Carpenter, all signed with notes thanking the Massachusetts General Hospital surgeon for getting them back into the games.

Two pictures, separated from the rest, stand out. In one, several servicemen are pushing a helicopter off a naval carrier into the South China Sea. In the other, the chopper has flipped upside down and is slowly sinking beneath the waves. It was Zarins, a doctor and amateur cameraman standing on the deck of the USS Okinawa, who snapped the pictures during the fall of Saigon in 1975.

In advance of this weekend’s premiere of “The Vietnam War” a 10-part documentary by filmmakers Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, Zarins recently recounted his involvement in the evacuation of American personnel and Vietnamese civilians fleeing the approaching North Vietnamese army in April of that year.

Zarins had joined the Navy following his medical residency, and he became head of orthopedics at the naval regional medical center on Guam. There he also led the center’s emergency medical team, whose members were trained to set up and man makeshift field operating rooms to treat the wounded. In the war’s waning days, Zarins’ unit got the call to action.

“Our assignment was going to be to set up an emergency treatment hospital in the embassy there in Saigon,” said Zarins, the Augustus Thorndike Clinical Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Harvard Medical School. “We were going to be in Saigon because there were 10 communist divisions surrounding it.” A fierce battle and heavy casualties were expected.

His group was flown to the helicopter carrier USS Okinawa off the coast of Vietnam, where it awaited the orders to deploy. But the orders never came, nor did the final attack. Instead, the North Vietnamese delayed their invasion long enough for thousands to flee. Some were plucked from the roof of the American embassy by helicopters and shuttled out to sea.

“Once in a while, a Vietnamese helicopter would fly over and land on our carrier,” said Zarins, recalling how South Vietnamese army pilots packed their own choppers with family members and friends and flew them to the U.S. ships offshore. “But the carrier could only hold so many things, and there was no room to keep these extra helicopters, so they emptied them out and just dumped them overboard. I was standing on the ship waiting to see what was going to happen — we were just on call, ready to go in — so I took these pictures of them dumping these helicopters in the ocean.”

Zarins was pressed into service the following day as injured evacuees were ferried from other vessels to his ship for treatment.

“That evening they arrived with 20 serious injuries,” he said, recalling a man who had a compound fracture of his tibia, and another with a broken spine. One young mother’s arms had been crushed between two ships when she reached for her child, who had slipped from her grasp. “She had compound fractures on both elbows,” said Zarins. “We operated for 24 hours straight without stopping. We had to operate in our shorts. There were no more scrub suits or anything like that. We ran out of drills, so we sent to the machine shop on the ship to sterilize their drills.”

Ironically, Zarins was also injured.

Image gallery

“I was jogging on the deck and tripped. I fell on an outstretched wrist and broke [it], so I had the guys put a cast on it. When all these injuries came in, I just cut it off and operated.”

Later, he and his team took care of the sick and injured at makeshift refugee camps in Manila and accompanied 4,000 refugees on a cargo ship headed to Guam.

For Zarins, watching Vietnamese civilians fleeing the communist forces evoked an eerie déjà vu; he had once been “on the other end of it, and now we were helping other people do the same thing.”

Born in Latvia, Zarins, his parents, and two young siblings fled Russian troops as they advanced on the country near the end of World War II. “Russians were killing the intelligentsia, and our family was going to get deported or killed. Everybody was trying to get out, so we went to the shore … and we happened to get on a little fishing boat that went to Sweden. It was sort of chance that we even got on.”

It was lucky his little brother, Christopher — who would grow up to be chief of vascular surgery at the University of Chicago and then Stanford University Medical Center — made it to the fishing boat at all. To keep the 6-month-old safe from shore-based gunfire, someone had tucked him under a seat in the dinghy that was rowed out to the waiting trawler. The baby was nearly lost in the nighttime chaos.

“The last person getting out of the boat happened to stub their toe on him,” said Zarins of Christopher. “Otherwise, they would have left him.”