‘Where the Roads All End’ is where story begins

Peabody curator offers in-depth look at Marshall family’s collection and impact of their presence

Striking in their beauty and their intimacy, the photographs the Marshall family made during their eight expeditions into the Kalahari from 1950 to 1961 have pure visual appeal. Landscapes of flowering fields or towering baobab trees and dominated by a majestic sky alternate with portraits of a family’s growth and change.

It is that change — beyond the stunning aesthetics — that mark these photos as special, forming the impetus behind “Where the Roads All End: The Marshall Family’s Kalahari Photography,” a talk and slide show this past Wednesday by Ilisa Barbash, curator of visual anthropology at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology. Drawing from Barbash’s book “Where the Roads All End: Photography and Anthropology in the Kalahari,” the presentation included rare 3-D stereoscopic images.

The Marshall family, who made these trips between 1950 and 1961 under the sponsorship of the Peabody, which is celebrating its 150th year, were educated amateurs when they set out for Namibia (then South West Africa) and Botswana (then Bechuanaland). The Ju/’hoansi, the people the Marshalls sought to meet, and whose lives they ended up chronicling, were at that point living in a manner that was beginning to change. As captured in the photos, father ≠Toma, mother !U, and their extended family were on the brink of leaving behind the traditional, nomadic life of their people as farmers, ranchers, and the forces of Westernized national governments expanded into their territory.

The Marshalls, explained Barbash, who is the museum’s first curator of visual anthropology, were “salvage anthropologists,” intent on documenting a disappearing culture. Barbash, herself a documentary filmmaker, described her own introduction to their work, largely through the documentary films of John Marshall, who was a budding 18-year-old filmmaker during the first expedition. She then went on to explain how John joined his parents, Laurence and Lorna, and sister, Elizabeth (the author of such books as “The Hidden Life of Dogs” and “The Harmless People”), who had just started at Smith College, as well as various drivers, translators, and other staffers in what was an arduous, weeks-long journey of no certain outcome.

Advised to search for “the wild bushmen,” Barbash explained, the Marshalls would come to drop the phrase, which is seen as pejorative, for the indigenous people’s own term for themselves, the Ju/’hoansi (they also visited the G/wi people). As they lived with and studied these people, they documented their changing lives in 40,000 photos in both color and black and white, as well as the 3-D stereoscopic images. These photos are the basis for Barbash’s book and for the evening’s presentation, which was highlighted by slides of those stereoscopic images, for which the audience was given special viewing glasses.

As these images glowed on screen, Barbash read excerpts from her book, often quoting the family’s eight diaries, as well as numerous notebooks and letters. Slides of the veldt, with its stunning open space, gave way to photos of families preparing food and caring for children. Hunting and gathering, which actually provided a larger part of their diet, are documented. Throughout the individuals are named, a dignity often overlooked by previous anthropologists, and even in the hourlong presentation, a sense of individuals and personality came through.

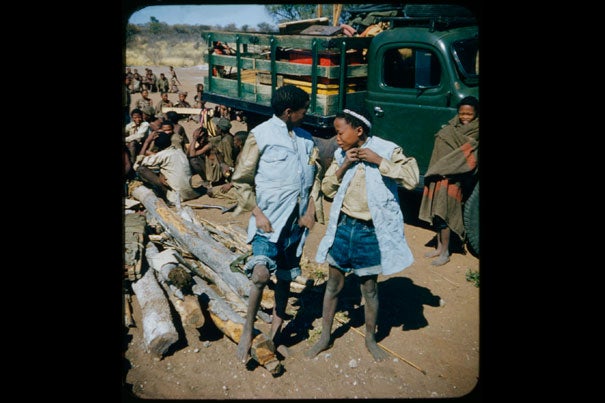

The Marshalls themselves also emerge as characters in the drama. As Barbash read, it became clear that Lorna, in particular, came to question the expedition’s role in the Ju/’hoansi’s changing life. At one point, they gave the indigenous people Western-style clothes, Barbash said, before reading what she described as a “very poignant, extremely sad and meaningful observation.”

“We started to leave,” Lorna wrote. “The bushmen, their eyes shining, began struggling into the clothes. In an instant it happened, their beauty and dignity vanished. They became ridiculous.”

“What have we done, making a track into this country?” Lorna would later ask herself. “If we could go back, I would not come here.”

Such changes could be seen, notably in a series of photos of N!ai, ≠Toma’s niece. First pictured as a toddler, she squats with her half-brother /Gaishay, utterly unfazed by the photographer as she drinks water from an ostrich eggshell. When we next see her, as a teenager, she wears traditional beads, a Western-style headscarf, and a decidedly suspicious expression. In the final photo, from 1961, she is dressed entirely in Western fashion, and although she smiles at the camera, it is slightly unnerving how her consciousness of — and, perhaps, investment in — the modern world had changed.

“Where the Roads All End: Photography and Anthropology in the Kalahari” may be purchased at the front desk of the Peabody Museum or through Harvard University Press.