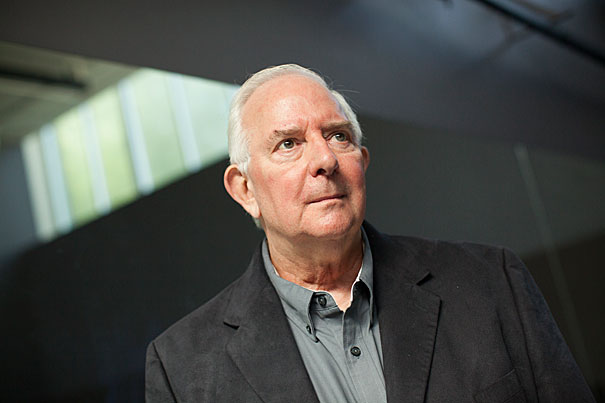

“The time is right,” said David Chambers, a visiting professor in Theater, Dance & Media. “We have to have a community consensus that we can’t physically hurt each other, but we can argue passionately, be controversial, and turn humor into a flamethrower.”

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

No rest for the witty

Writers and performers re-energize long tradition of mining D.C. for comedy gold

Comedians aren’t joking around in the current political climate, using humor as a legitimate form of discourse no less penetrating than scholarly essays or newspaper op-eds.

“The time is right,” said David Chambers, a visiting professor in Theater, Dance & Media. “We have to have a community consensus that we can’t physically hurt each other, but we can argue passionately, be controversial, and turn humor into a flamethrower.”

The humor, some of it scathing, much of it biting, reveals itself with every zing at the Trump administration from late-night hosts Stephen Colbert, Samantha Bee, and Trevor Noah. “Saturday Night Live” has also joined in the fun, scoring its highest ratings in more than 20 years thanks to the kind of in-your-face comedy that has the power to start and steer conversation — sometimes inside the White House itself.

Melissa McCarthy (as White House press secretary Sean Spicer), “SNL” cast member Mikey Day (Trump adviser Steve Bannon in a Grim Reaper costume), and Kate McKinnon (adviser Kellyanne Conway) have all played a role, and Alec Baldwin’s impersonation of the president has drawn social media pans from the commander in chief.

“The idea of the mask allows them and us to put these figures into an elephantine proportion, blown up 10 or 12 times, which has always been a source of political comedy,” said Chambers. “Deep humor lies in the mask — the mask of the Grim Reaper, the mask of Sean Spicer. In one skit, McCarthy took the podium and pressed people back into the pigpen of reporters, literally using the bully pulpit as a weapon of extinction.

“It was deeply funny. For the performer, the psychological premise is: The mask made me do it. But it’s not just the mask but the physicality, which takes an element of the character being portrayed, and expands it to a grotesque level.”

Chambers, who served as faculty adviser to students starting the Harvard Cabaret in 2015, likened “SNL” to cabaret, calling it fun and transgressive.

“You get to be a little mean and start little fires. It’s social arson,” he said.

He noted that cabarets with political satire originated in Paris in the late 1800s and were exported throughout Europe around the turn of the 20th century. In Germany and Poland, Jewish variety shows continued late into the Hitler era, stages for gallows humor and maudlin songs even in the concentration camps.

“They were a very vital place. Jews couldn’t go to a synagogue or gather publicly, but these cabarets, which had innocent names such as the Kit Kat Club, became a kind of sanctuary, a meeting place where fear could be faced with humor and song,” Chambers said.

Comedic treatment of serious political issues goes back further, said Derek Miller, assistant professor of English, who pointed to how the comedies of Henry Fielding prompted the British government to enact the censoring Theatrical Licensing Act of 1737. “He was going after government, and they shut him down,” said Miller.

Miller noted that the White House has long been a target of comedy, naming as an example “Of Thee I Sing” (1931), a Pulitzer Prize-winning musical satire that tells the story of a fictional presidential candidate running on a campaign platform of “love.” Both Miller and Remo Airaldi, lecturer in Theater, Dance & Media, recalled “SNL” star Chevy Chase’s memorable 1976 impressions of President Gerald Ford, from Ford spilling water in one skit to hanging Christmas stockings upside-down in another. The parody was so compelling that it changed Americans’ perception of their “accidental” president.

“‘SNL’ seeps down to the culture,” said Airaldi, who is teaching “Introduction to Improvisational Comedy” this spring. “This klutz bit — after a while it was how people thought of Gerald Ford.”

Humor falls into two categories, in Airaldi’s view: something recognizable in human behavior, or a surprise. Comedians skewering the new president have found great success with audiences because they are addressing the latter.

“In Trump, the element of surprise is why they laugh,” he said. “They can’t believe it’s happening. They can’t believe they have a president who acts this way.”

Though late-night stars have dominated the post-election spotlight, Airaldi expects the sitcom to find its political funny bone in formidable ways, just as happened in the 1970s. Soon, the professor said, we might see a Trump-era version of Archie Bunker, the working-class bigot at the center of the popular “All in the Family,” or Maude, who had an abortion on her self-titled show.

“The Norman Lear sitcoms of the 1970s reflected a culture that was steeped in political and social change after Watergate and the Civil Rights Movement,” he said. “It feels like we are now in a similar environment, and shows that don’t deal with the political conversations we’re all having will start to seem out of touch.”

Closer to campus, SatireV, an online magazine penned by Harvard undergrads, has been mocking the Trump administration as steadily as it pokes fun at campus news. In a recent piece “written” by Sergey Kislyak, the Russian ambassador laments his downward social spiral in the wake of the Jeff Sessions controversy.

“What Am I Supposed to Do with This Dinner Reservation?” Kislyak asks in the title of the essay, going on to lament: “We spent an entire weekend hunting dangerous game together in the Caucasus Mountains, and you’re just gonna act like we’re not even friends.”

Editor in chief Dan Kenny ’18, a government concentrator, said writers group chat in rapid-fire style about breaking news, which has been hard to keep abreast of given the president’s steady stream of executive orders.

“Our audience is mostly liberals, and we make fun of them too,” said Kenny. “They’re not out of bounds — even in the Trump era.”

SatireV president Toni Chan ’18, an economics concentrator, said the Trump White House has been easy material — maybe too easy.

“Jokes about Trump’s personality or the personalities of his administration are pretty predictable and fatigued at this point,” she said. “We’ve made our fair share of those, to be clear, but we’re also trying to focus on going beyond just pointing out hypocrisy, to satirize policy and political figures in a more meaningful way.”

Associate editor Nathaniel Brodsky ’18 sees humor as a form of resistance.

“We’re not doing the same work as calling a swing state senator, but it’s an act of defiance,” said the English concentrator. “If we can make the people who are making protests and leading phone banks laugh, it’s a small gesture, but a meaningful one.”