Saying no to the Dakota Access Pipeline

Opponents of project under Sioux land see echoes of past injustices

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe’s recent protests against building the Dakota Access Pipeline under their lands marked another chapter in the long history of struggles Native Americans have faced to protect their property, resources, and way of life, speakers told a Harvard audience Friday.

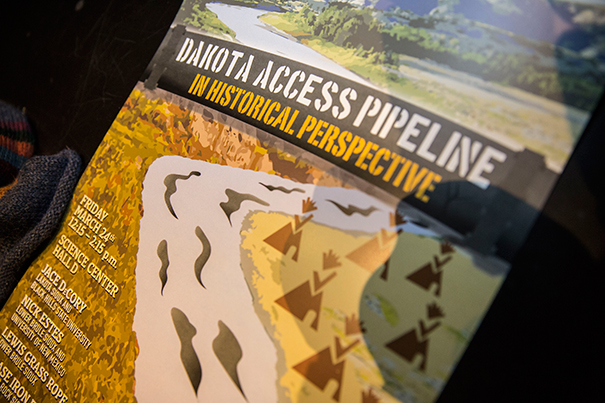

The panel at the Science Center emphasized the importance of bringing historical perspective to the fight over the pipeline in North Dakota, which is to go under an area that provides drinking water, and of linking the protests to such broader themes as national sovereignty, oppression of people, and destruction of the natural environment.

“What was clear was that this was about … protecting water supplies, but it was far more about history, about a very long and deep history,” said moderator Lisa McGirr, a Harvard professor of history.

McGirr said that during a visit she made this past fall to the main protest camp, Oceti Sakowin, she saw firsthand “the incredible devotion, dedication, passion, sacrifice, and spirit” of the protesters.

Sponsored by the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History and the Harvard University Native American Program, the forum came a month after the camp was cleared by authorities, effectively ending the protest. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers earlier that month had approved the project.

Supported by other opponents, the Standing Rock Sioux contend that the pipeline, which is being built under the Missouri River near the tribe’s reservation, endangers the drinking water supply and would pass through some of its sacred lands.

Jeffrey Ostler, professor of Northwest and Pacific History at the University of Oregon, said he was struck by the way the Standing Rock episode echoes “an earlier history of settler colonialism in the 19th century.”

Ostler cited an 1874 military expedition led by Gen. George Armstrong Custer that confirmed rumors of gold on sacred Lakota land in the Black Hills of South Dakota, and a subsequent expedition led by Col. Richard Dodge. He said Dodge’s report on his mission was a “bundle of lies,” falsely claiming that the land had never been a permanent home for Indians and that the Lakotas did not want it.

“When I hear accounts of pipeline proponents dismissing the water protectors’ claims that the pipeline’s construction has damaged graves and other sacred sites and that it threatens a sacred resource, water … I can’t help but place them in a long history of settler colonial claims,” he said.

Chase Iron Eyes, a member of the Standing Rock Sioux and South Dakota counsel for the Lakota People’s Law Project, said the centuries of mistreatment of Native Americans are part of a wider historical story of the oppressive effects of colonization.

“For me, colonization not only represents what happened to us but what happened to you,” he said, “to those of you who are of Anglo descent who were separated from your food source … whose minds were separated from their spirits.”

The peaceful protesters were “trying to exercise and protect their inherent right, but also every American’s constitutional rights,” Chase Iron Eyes said.

Nick Estes, a member of the Lower Brule Sioux, also sought to put the pipeline episode in the broader context of the impact of racism, colonialism, and capitalism, topics he explores in a forthcoming book.

“In the 1870s, capital wanted the gold in the Black Hills. In the 1890s, capital wanted more land for white settlers in South Dakota,” he said. And in the 1950s, he said, the need for water to meet irrigation and public drinking supply needs led to the creation of dams on the Missouri River that flooded more than 300,000 acres of mostly Sioux land.

“Over 1,000 indigenous families were forcefully dislocated from the reservation territories,” said Estes, adding that the dams “personified” settler colonialism and capitalism. Now, “We have oil pipelines saving the economy at the expense of indigenous peoples. The oils themselves personify capitalism because they solidify settler states’ control over indigenous lands.”

“Self-defense sometimes means putting your body between settlers and their money,” he said. He praised the water protectors “for reminding us of that.”

Jace Cuney DeCory, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux and assistant professor of history and American Indian studies at Black Hills State University, said her family was among those displaced by the Missouri River dam project.

“My grandmother was saddened because their lands were flooded,” she said. “And we talk about flooding lands now with oil and gas pipelines. It seems like history repeats itself.”

But she sounded a note of optimism.

“We’ve survived as a people because our ancestors did not give up,” DeCory said. “We are resilient. We’re strong. We’re spiritual people. Our voices are being heard, finally.”