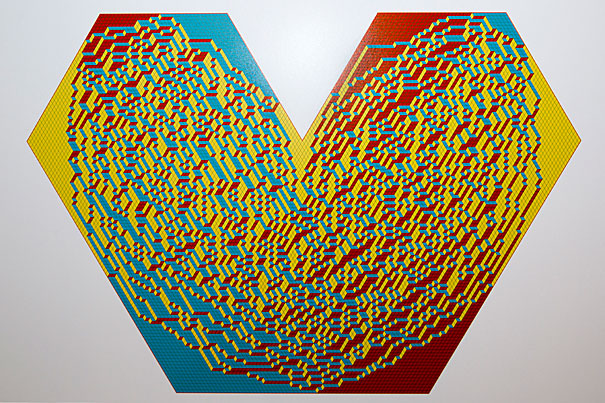

“Random Heart” is a computer-simulated image that is part of “The Art of Discovery,” an interdisciplinary art show at the Radcliffe’s Johnson-Kulukundis Family Gallery. The work is by Radcliffe Fellow and mathematician Alexei Borodin and Leonid Petrov.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Mixed messages

New Radcliffe exhibition pushes artistic boundaries

It’s an eclectic exhibition.

An interstellar image hangs next to videos of tiny ocean organisms swimming through their own vast universe. Close by, a slab of black shale stands out atop a white stand. Language doubles as visual art in a series of photos with bits of graffiti from the occupied West Bank and Jaffa, Israel.

“The Art of Discovery,” running through Oct. 29 at the Radcliffe Institute’s recently revamped Johnson-Kulukundis Family Gallery, showcases work by 13 current fellows, including scientists, a mathematician, an anthropologist, even an urban planner.

The exhibit “exemplifies the core Radcliffe principle of commitment to the arts as a method of inquiry integrated with other forms of study,” said Radcliffe Dean Lizabeth Cohen, delivering brief remarks during the exhibition’s opening reception last week.

Image gallery

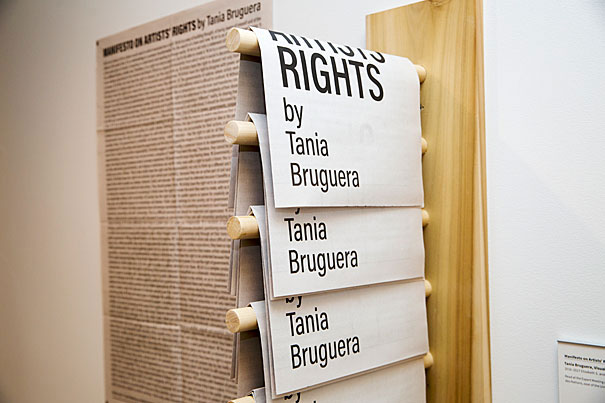

A piece entitled “Manifesto on Artists’ Rights” by Tania Bruguera. The Art of Discovery, a multidisciplinary group exhibit of 2016-2017 Radcliffe Institute fellows, is on display at the Radcliffe galley in Byerly Hall. The show features the work of artists alongside works by historians, scientists and astronomers. Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

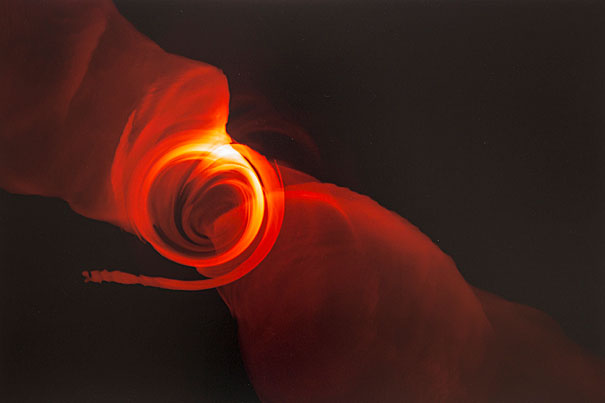

“Black Hole in the Center of the Milky Way 2” by Dimitrios Psaltis, Chi-Kwan Chan, and Feryal Ozel, Astronomy. The Art of Discovery, a multidisciplinary group exhibit of 2016-2017 Radcliffe Institute fellows, is on display at the Radcliffe galley in Byerly Hall. The show features the work of artists alongside works by historians, scientists and astronomers. Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Plankton Chronicles” by Chris Bowler, Biology. The Art of Discovery, a multidisciplinary group exhibit of 2016-2017 Radcliffe Institute fellows, is on display at the Radcliffe galley in Byerly Hall. The show features the work of artists alongside works by historians, scientists and astronomers. Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

“From This”, Fayetteville shale collected from an outcrop, by Conevery Bolton Valencius, History. The Art of Discovery, a multidisciplinary group exhibit of 2016-2017 Radcliffe Institute fellows, is on display at the Radcliffe galley in Byerly Hall. The show features the work of artists alongside works by historians, scientists and astronomers. Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Hydroxyapatite flowers grown on a bioceramic, scanning electron micrograph, by Hala Zreiqat, Materials Science. The Art of Discovery, a multidisciplinary group exhibit of 2016-2017 Radcliffe Institute fellows, is on display at the Radcliffe galley in Byerly Hall. The show features the work of artists alongside works by historians, scientists and astronomers. Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

That integration was well underway at the crowded afternoon event. An astronomer discussed her work with a visual artist and a wordsmith carefully surveyed the gallery that included a video about a housing project in New York as well as her own “acrostic elegies.” Nearby, a historian with a passion for science explained to onlookers how hydraulic fracturing releases the gas contained within shale, such as the small sedimentary slab she’d found along a highway in Arkansas and included in the show.

“By bringing a piece of Fayetteville shale into an art gallery, I wanted to emphasize the beauty and wonder that are part of the technologically complex, economically vital, and scientifically complicated questions of how we produce our energy,” said Conevery Bolton Valencius, a history professor at Boston College who will work on a book about the link between hydraulic fracturing and earthquakes during her fellowship.

Biologist Chris Bowler’s addition to the show, the mesmerizing “Plankton Chronicles,” attracted a steady stream of viewers. The piece, created by Christian Sardet, Bowler’s colleague at France’s Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Lyon, aims to expand the understanding of plankton beyond simply “food for the whales,” said Bowler, and encourages viewers to “appreciate their beauty and their importance for keeping our planet habitable.” Bowler will use his time at Radcliffe to study the potential effects of climate change on plankton.

Visual artist Tania Bruguera, whose “Manifesto on Artists’ Rights” is based on a talk she delivered at the United Nations office in Geneva in 2012, called being part of an exhibit that blends works by artists and non-artists “fantastic.”

“It actually proves that there is an easy overlap between all our practices,” said Bruguera, who will devote her fellowship to further work on the Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt, an art institute in Havana and an online platform that promotes civic literacy in Cuba. The opening lines of Bruguera’s “Manifesto” highlights her point.

“Art is not a luxury,” it reads. “Art is a basic social need to which everyone has a right. Art is a way of building thought, of being aware of oneself and of the others at the same time.”

The reception attracted a Harvard newcomer with a deep interest in interdisciplinary collaborations and merging art with science and other fields of inquiry. Martha Tedeschi, the Elizabeth and John Moors Cabot Director of the Harvard Art Museums, encouraged the fellows to stop by the Museums, and in particular to explore the Art Study Center, where visitors can request works for up-close inspection.

The Harvard Art Museums are “a resource for you if you are looking for some kind of visual inspiration that might spark a conversation,” she said.