Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton and Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump will seek to “not lose” in front of a television audience that is expected to rival the Super Bowl’s.

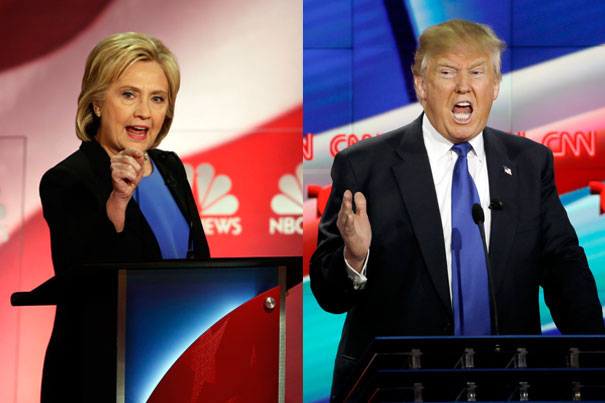

Photos (left) by Mic Smith; (right) by David J. Phillip

Debating the debates

Harvard analysts ponder the upcoming presidential clashes, how viewers may react, and how the candidates might snare their votes

More like this

Whether looking for some reason, any reason, to support one candidate over another, or just wanting to watch high-stakes political mud wrestling, millions of Americans will tune in Monday night to see Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump face off in the first of three presidential debates.

In this tumultuous and divisive election cycle where even the usually sleepy primary debates garnered record ratings, the first head-to-head matchup between the Democratic and Republican nominees is expected to be among the most watched television events of the year.

Historically scheduled late in the run-up to Election Day, presidential debates purport to offer the public an easy way to learn about the candidates, to compare and contrast them side by side on the issues as well as on their demeanor. The first modern debate in 1960 between John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon set the bar for how a candidate came across to voters could make — or break— his chances of winning the election.

But over the years, as the news media declared winners and losers based on the “big moments” — on who got off a good quip on his opponent or, worse, who made himself look bad, like George H.W. Bush checking his watch in 1992 or Barack Obama looking down as he peevishly scribbled on a notepad in 2012 — the debates have come under frequent criticism for stoking conflict and emphasizing theatrics over substance or a civil exchange of ideas.

Now, as the race tightens between Clinton and Trump and many would-be voters remain undecided or unenthusiastic about both candidates, Harvard analysts say that while there is some truth to criticism that the debates are more “show” than “business” in this era of endless social media and nonstop campaigning, there is still much to glean from seeing candidates sparring under a white-hot spotlight.

Clocking the candidates

As Clinton and Trump prepare to debate Monday night, each candidate has some clear weaknesses to try to counteract with their performances, debate experts say.

Clinton’s reputation as a stiff, lawyerly speaker whose vast knowledge of policy minutiae doesn’t connect emotionally with people stands in sharp contrast to Trump’s brash, freewheeling style that delivers intuitively but offers little depth or substance.

“Each of them has to understand the persona that they’ve already created and then see if they can soften the edges of that persona in the context of the debate,” said lecturer Marie Danziger, the former director of Harvard Kennedy School’s (HKS) communications program who now teaches “The Arts of Communication.”

“Hillary’s challenge is to imagine herself in a one-on-one with Trump at a dinner party or over drinks and give the impression that she’s comfortable with this kind of confrontation, that she can tease him a little instead of acting as if she’s being attacked. She’s got to try and hide her scars in these debates,” Danziger added.

“She’s got to show she’s got a human side,” said Steve Jarding, who trains students to debate and teaches campaign strategy at HKS. “She’s got to do what she did in New Hampshire eight years ago, and don’t be afraid to show some emotion. I think the worst thing is to keep this wall built up around her because that makes her look almost robotic at times, it makes her look less sincere, it makes people cynical about her.”

For Trump, “He’s got to show that he’s in control, which is almost impossible; he can’t take cheap shots. He can’t be this snide, cynical, mean-spirited person — he’s got that group. He’s got to show that mainstream voters shouldn’t fear him,” Jarding added, noting that Trump has the bigger hill to climb in preparing because he’s not as deeply informed as Clinton on the issues.

“It’s easier for her to try to be more human than it is for him to become ‘smart’…. There’s too much out there. I would not try to make him ‘smart’ on the issues because it’ll fail. If I’m training with Donald Trump, we’ve got to try to make him friendlier, we’ve got to say, ‘You’ve got to show that you can be presidential.’”

“I do think that Trump, although he can get away with more of that than any other man I can think of, has to be very careful he doesn’t disrespect her in any kind of sexual or gendered-type putdown,” said Danziger. “Nothing the least bit provocative. That’s one way he can blow it.”

“I really think in light of their flaws, in light of 60 percent of the American public saying ‘We don’t like either one,’ they’ve both got a ton of work to do,” said Jarding. “And there’s no better forum than a lengthy debate.”

No small matter

With candidates now arguing issues and policy positions on social media nearly every day, many observers question whether the presidential debates are still relevant or effective tools to persuade voters before they head to the polls. Yet some Harvard faculty contend that demanding candidates to ask and answer tough questions for 90 minutes, without help from teleprompter and without media interference, is one of a precious few unfiltered moments in a campaign.

“What’s special about these is the chance for millions of people simultaneously to hear from the candidates in their own words and let them define — or try to define — what they’re all about, what their agendas are like, what their capacity for leadership is, how their experience dovetails with the requirements of the presidency,” said Thomas Patterson, Bradlee Professor at the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at HKS.

“I know journalists like to say these things are nothing but sound bites and canned arguments, but … [studies show] that for a lot of people, it’s relatively new … and most people say they learned something from listening to them. The journalists may have been hearing the same speech for six months, but that doesn’t mean that the typical viewer has,” said Patterson, who has done a series of analyses of the 2016 election media coverage and will study the debate coverage later this fall.

“I think they’re extremely important, and more important than ever,” said retired CBS News anchor Bob Schieffer, who has moderated three presidential debates and served on the Commission on Presidential Debates until last January. “They’re one of the events that stills move the needle.”

“If they live up to it, I think the debates are the three most critical days in the campaign,” said Jarding.

“Surveys suggest more and more undecided voters make up their minds with debates than ever before, so the public is paying attention, and it does matter to the public. Now, having said that … all the players have to step up, including journalists and moderators … so that we can have follow-up [questions]. We cannot let a candidate somehow filibuster an answer or not give an answer. They have to be called to task,” he said. “They’re only a sham if we let them be.”

For the candidates, debates are high-risk events with fairly low rewards.

“We train students not to lose, as opposed to win, because it’s hard to win a debate unless somebody screws up. Then it’s Dan Quayle quivering when Lloyd Bentsen says ‘You’re no Jack Kennedy.’ The rest of that debate, Lloyd Bentsen didn’t win, but that sealed it,” he said.

For those working on campaigns, getting ready for a presidential debate is grueling.

“They’re a minefield you’re just trying to get through,” said Jarding, who has prepped candidates. “The campaign-person power that it takes to put together the campaign books, research the policy, have the policy team and the opposition and self-research guys try to prepare answers and questions that you can ask your opponent to try and trap them, give you answers on questions you think they’re going to try and trap you on — it takes hundreds and thousands of man and woman hours to prepare for two hours of TV time when at most, unless there’s a screw up, it’s going to be a tie,” he said. “So as a manager, you hate them. They’re such a waste of time.”

With the race between Clinton and Trump tightening, even a very good performance won’t drive a mass migration from one side to the other, the analysts said, yet even tempered shifts can prove significant.

“You’re not going to have 100 million people watching the debate and 100 million people make up their mind or change their mind,” said Jarding. “Elections are won at the margins. If, let’s say, Trump is down five, six points in the national polls, he gets 2, 3 percent that he pulls from her and moves to him, that can be the election.”

What it takes

What goes into an effective debate performance, and good public communication more broadly, are Aristotle’s logos, pathos, and ethos, said Danziger.

“Logos is the quality of the rational argument: Are there some meaningful facts and figures involved? Pathos is: Is there emotional impact; can the candidate talk about how this issue affects real people with real feeling? But most important is ethos: And that is the personal trustworthiness, likeability, [and] authority of the speaker.”

While candidates are expected to answer questions with something resembling the relevant facts, Danziger says ultimately it’s the values that underline those answers that really touch voters.

“It’s all about public speaking as a two-way street where you’re trying to answer the questions on the turf of your audience,” she said. “‘I understand your concern, I understand your fear, I understand your objection, and here is my best attempt to respond to that underlying emotion.’” It’s a skill President Bill Clinton really mastered, she added.

The psychodynamic relationship between public speakers and their audience is very complex, akin more to a tango than a tennis match, where facts and barbs fly back and forth, Danziger argues. “It’s a kind of power play, but it’s also a seduction. How do you control that dynamic? It’s partly about building trust, but it’s also about projecting leadership and confidence, while at the same time allowing yourself a certain amount of vulnerability and making it a two-way street,” she said.

Though Trump’s shoot-from-the-hip style has come under fire for degrading the political discourse, win or lose, his informality appears here to stay.

“What makes these upcoming debates so interesting is that whatever else he has done or hasn’t done, Trump is changing the style of our political rhetoric,” said Danziger. “And I don’t mean to suggest it’s all for the bad. I think that this authenticity idea, the fact that ‘I’m going to say what I believe, I’m not going to be the same old, same old bureaucratic politician’ — I think from now on, every politician is going to have to project some of that.”

Only in moderation

The historically low percentage of voters who say they find Clinton and Trump honest or trustworthy, as well as Trump’s history of uttering falsehoods, as fact-checking organizations have reported, makes the role of debate moderator especially important and complicated this year.

“Today” show host Matt Lauer was widely criticized for failing to challenge Trump when he repeated an untrue claim that he had been an early opponent of the Iraq War, during a Sept. 7 town-hall forum on veterans’ and military issues.

“I think the first fact-checker ought to be the candidate,” said Schieffer, the Walter Shorenstein Media and Democracy Fellow at HKS. If neither candidate puts forward an accurate answer and things descend into bickering, only then should the moderator step in and correct the record, he said.

“I don’t care who the candidates are, interviewing somebody in real time, live, is different than when you can go back and check. I think you just have to do your best to be up on the issues and familiar with what they are to the best of your ability,” said Schieffer. “And the fact is, you’re not going to catch them all.”

If moderators see themselves as stand-ins for the profession of journalism, “I think that’s a mistake,” said Patterson. “They’re really stand-ins for the American public, and they really should be asking questions that voters would like to have answered” on major concerns that need solving, rather than the strategy and process questions that much of the press prefers.

And it’s not all about memorizing responses to complex policy questions, Schieffer says. “It’s not just the answers, but how the person answers. What the moderator’s goal should be [is] to give the American people the best possible picture of who these people are. You want to help people see how these people react under pressure, how they react in response to a critical reply to something they’ve just said.”

All sizzle and no steak

The debates may have started out as a simple way for voters to learn about candidates and their views on issues, but the ubiquity of social media and the press’s emphasis on spectacle and confrontation have diluted their civic value, argue some at Harvard Law School (HLS).

“In my view, they’ve gotten morphed into less about the candidates’ actual substantive views on an issue, and it’s turned into a slugfest and who can have the sound bite for the next morning. And that just seems to me to be counter to helping informed citizens in a democracy make an educated choice about who they might select for their leader,” said Robert Bordone, Thaddeus R. Beal Clinical Professor of Law and director of the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program at HLS.

“I think most viewers expect to see sound bites and fights, and that sort of expectation sets up the debates. It’s almost like the incentives to have a healthy dialogue between the two, with a debate on issues, are not there,” said lecturer Heather Kulp, who has co-written with Bordone about the need to overhaul the way presidential debates are run. “I think we underestimate what people would be interested in seeing.”

If Clinton and Trump abandoned the artifice of podiums and sat together on a couch and had a conversation rather than a war of words, perhaps their substantive views and ideas would be better elucidated, she said. “That’s going to be a lot more useful for the electorate than, ‘Well, Donald Trump’s a racist’; ‘No, Hillary Clinton’s a racist.’”

Social science research shows that deep distrust of political leaders often leads to a similar distrust of their supporters, even if they’re neighbors or friends. With two polarizing candidates in Clinton and Trump, it’s a dynamic that’s causing social and political harm, even here on campus, Kulp and Bordone say.

Partisanship “infects everybody to the point where we can’t even have conversations about issues of difference anymore with each other. We really avoid it, and how much does that hurt democracy?” said Kulp.

“So it’s not just the debates at a national level that hurt democracy. I think that is indeed a symptom of the fact that we can’t and don’t want to talk about difference anymore because we feel like we don’t have the capacity, we don’t have the words, because we see difference as a place where we can be fighting one another rather than actually having an interesting and helpful discussion with one another about those differences.”

Bordone and Kulp suggest candidates would be better off sitting together at a table and answering inquiries posed by a handful of questioners, similar to a group job interview. The questioners could be journalists knowledgeable on a host of topics or perhaps a pool of citizens who discuss the practical effects of legislation or policy positions. For example, a nurse, a home health care worker, a pediatrician, a professor, and a doctor who works with immigrants could talk about the Affordable Care Act and their ability to give care and ask candidates to tell them what needs to be fixed and how they’ll do it.

“Since one of the skills [as president] is that you have to work with people from a lot of different perspectives, including people who represent an entirely different political spectrum than you do, so how do you work with those people? Remove the audience, have one or two interviewers, and have the candidates engage in a project together or engage in a conversation together about issues that will really draw out what some of their skills, talents, abilities are to work with someone from a different political [vantage point],” said Kulp.

This fall, Bordone is leading a new reading group to teach HLS students, many of whom will go into politics or hold leadership positions later, how to talk about politically charged issues and negotiate differences.

“Leadership is not simply giving an eloquent speech or having a good, substantive policy proposal, or being the smartest woman or guy in the room. It’s figuring out how to talk with people of different views, how to listen to those people, and how to find some common ground to do something with them even when we disagree,” he said.

“In our teaching and our pedagogy, we’re really thinking about how do we equip and build and encourage skills where people can have conversations with each other across lines of difference?” said Kulp. “One of the challenges right now, so many of our students feel like, ‘What’s the point, why bother?’ There is no common ground. All they see is models of people in their own corner, reinforcing their own views, and preparing to fight the other. So we have to give them opportunities to experience reasons why it matters for themselves and their lives and for their country and their community.”