Photojournalist Randy H. Goodman returned to Iran after 33 years to see how life has changed for women since her visits to the country to document the hostage crisis at the U.S. embassy and the Iran-Iraq War.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The surprising women of Iran

Cambridge photojournalist challenges perceptions of Iranian women in latest exhibit

Between portraits of a diplomat and a teacher, a large black-and-white photograph depicts six young women wearing headscarves, serving food out of a large pot and engaged in the middle of a fiery discussion. One of those women would become the diplomat, another the teacher. Without the caption below the frame, one might not realize that these six women were occupying the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, where 52 Americans would be held for 444 days.

The photo is one of the most prized of Randy H. Goodman, a Cambridge-based political sociologist and photojournalist. While completing a master’s program at Boston University in 1980, Goodman was asked by journalism folk hero and BU professor William Worthy Jr. to join a grassroots delegation of scholars, activists, and journalists to document the unfolding hostage crisis. She was just 24 years old.

“I couldn’t get ‘yes’ out fast enough,” she says, laughing at her framed Iranian press pass from 1980.

Armed with a bachelor’s degree in political sociology and a talent for documentary photography, Goodman immediately recognized the opportunity to use her skills and education in a way few ever get. Working with Worthy, she would visit Iran three times from 1980 to 1983, documenting the hostage crisis, the first years of the Iran-Iraq War, and life in a changed Iran for CBS News and Time magazine.

Three decades later, Goodman went back to her photos from Iran, assembling “Iran: Images from Beneath a Chador” and touring with her exhibit through the United States and Europe from 2009 to 2011. Following the show’s success, Goodman wanted to publish a book about the women she had photographed, but felt that the collection painted an incomplete picture after so many years. When it was announced that the Iran nuclear deal would be signed in the summer of 2015, Goodman saw the perfect opportunity to finish the story. As the world waited for the two bitter nemeses to finalize the agreement, she traveled around Tehran and the surrounding areas, asking women if she could take their pictures.

The outcome was “Iran: Women Only,” a comparison of Iranian womanhood in the early 1980s with the present. After openings at MIT and Harvard’s Gutman Library earlier this year, the exhibit moved to CGIS Knafel on July 30 for a monthlong showing.

The title borrows its name not simply from the photos’ subjects — almost exclusively female — but from the hard-to-miss, if not misleading signs designating gender-segregated areas of the Tehran Metro. “When you see the subway sign that says ‘Women Only,’” Goodman explained, “it doesn’t mean women have to exclusively ride in those cars. The first and last cars are usually reserved for women, and then there are cars in the middle where both men and women ride. If women want to ride in [segregated] cars for safety and security, they can.”

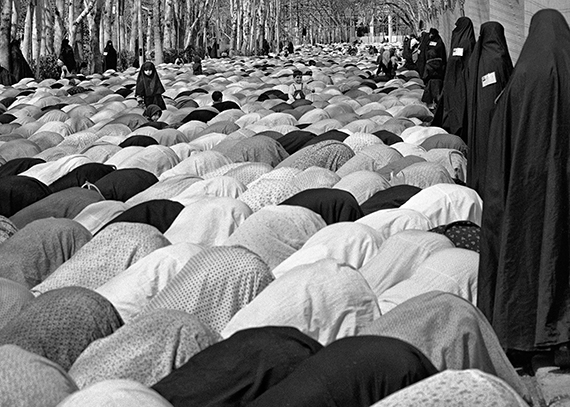

It is a strangely conscientious policy in a country that still resists acknowledging women as equal to men, Goodman points out. Even in the integrated buses and train cars, women still have to sit in the back. Courts do not weigh women’s testimony as heavily as that of men, nor are they granted custody of their children in divorces. And in prayer, as seen in quite a few of Goodman’s photos, the women are not merely isolated, but physically partitioned off. “I’m not sure if they’re blocked from seeing the men, or from being seen.”

Contrary to warnings from family and friends, Goodman did not find herself subjected to anti-American sentiment. During a shoot of a public prayer in 1983, female Revolutionary Guards noticed that she was with the press and took her to better vantage points. Regular civilians were similarly eager to be photographed and to lend a helping hand when she seemed out of place. “They always tried to help me — the Westerner,” Goodman says. “One time they put a chador on me so I’d fit in during Friday prayer. People were trying to reach out.”

Image gallery

Two girls hide their giggling as their picture is taken in 1983. Expectations of female modesty require that all women past a certain age must cover their hair with a hijab and dress in neither revealing nor form-fitting clothing. © Randy H. Goodman

Twin sisters posing for a photo in Tehran in 2015. Many young women in Iran have been pushing the boundaries of modesty in recent years, wearing loose, colorful scarves, getting their nails filed and painted, and wearing makeup. © Randy H. Goodman

What Goodman captures in her photography is the indomitable spirit of Iranian women in good times and bad. This is beautifully represented in the exhibit’s sprawling centerpiece: a large black-and-white photo of two shrouded, giggling girls from 1983 — themselves an anthropomorphic yin-yang — encircled by some 30-odd color photos of contemporary Iranian women. Far from the dour image most Americans have of Middle Eastern women, Goodman’s subjects are laughing, shopping, and exploring — all without a man in sight.

“These women who I see now may have been those young women that I photographed,” Goodman says. Pointing to a few of her favorite examples — two women hiking, teenage girls recording video on their smartphones, sisters out on the town in colorful clothing — Goodman recounted a recent run-in at the Gutman Library with a young woman who was sending her Iranian mother photos of the exhibit on her phone. She thanked Goodman for showing Iranian women smiling and looking happy.

The shift in cultural definitions of modesty is on full display in a larger group shot of several young women at a jewelry kiosk, centered on one in particular: a young woman wearing a bright, loose-fitting scarf, her nails filed into candy-apple-red points, with a white bandage taped across her nose, her skin still bruised from cosmetic surgery. “They see the image of the West and people want to change in order to look more like that — to go out on the street and have a bandaged nose is a status symbol,” Goodman says, noting how surprised American viewers are to learn that Iranians admire and emulate Western culture. “All the ways you would think that women can’t express themselves are almost in contrast [with reality].”

While this seems to signal a liberalizing of Iran’s culture and politics, Goodman is quick to point out that it is hardly a national phenomenon. The exhibit’s signature photo depicts a female cab driver staring at the viewer from inside her green taxi, “Women Only” clearly visible on the door. The cabbie may own her car, but her dress is traditional and her demeanor in line with expectations of modesty. In fact, her business specifically caters to those expectations. “On the one hand they’re modernizing, Goodman says, “and on the other they’re still being held back by a lot of traditions and customs that have become institutionalized.”

Goodman plans to return to Iran before the end of the year, hoping to delve a bit further into the lives of her female subjects. “I want to find more independent businesswomen … I didn’t get to explore [the female taxi driver’s] life in the way I would have liked to,” she said. “But also, I’d like to find the daughters of the women who occupied the embassy. One in particular is especially outspoken against her mother. She’s asking ‘Why should we honor you when — sure, we can drive, we can own businesses — but look at what you’ve saddled us with.’

It was Goodman’s experience in the embassy that helped her understand the country’s long and stubborn resistance to Western influence, even after 30 years. “Why should they become more Western?” she asks. “They’re struggling to find their own identity in a world that’s always changing.”

“Iran: Women Only” is on view in the Fisher Family Commons space of CGIS Knafel through Aug. 28. Goodman’s artist talk will be Tuesday (Aug. 9) from 4 to 6 p.m.

John Michael Baglione is a writer and author residing in Boston. His work can be found at johnmichaeltxt.com.