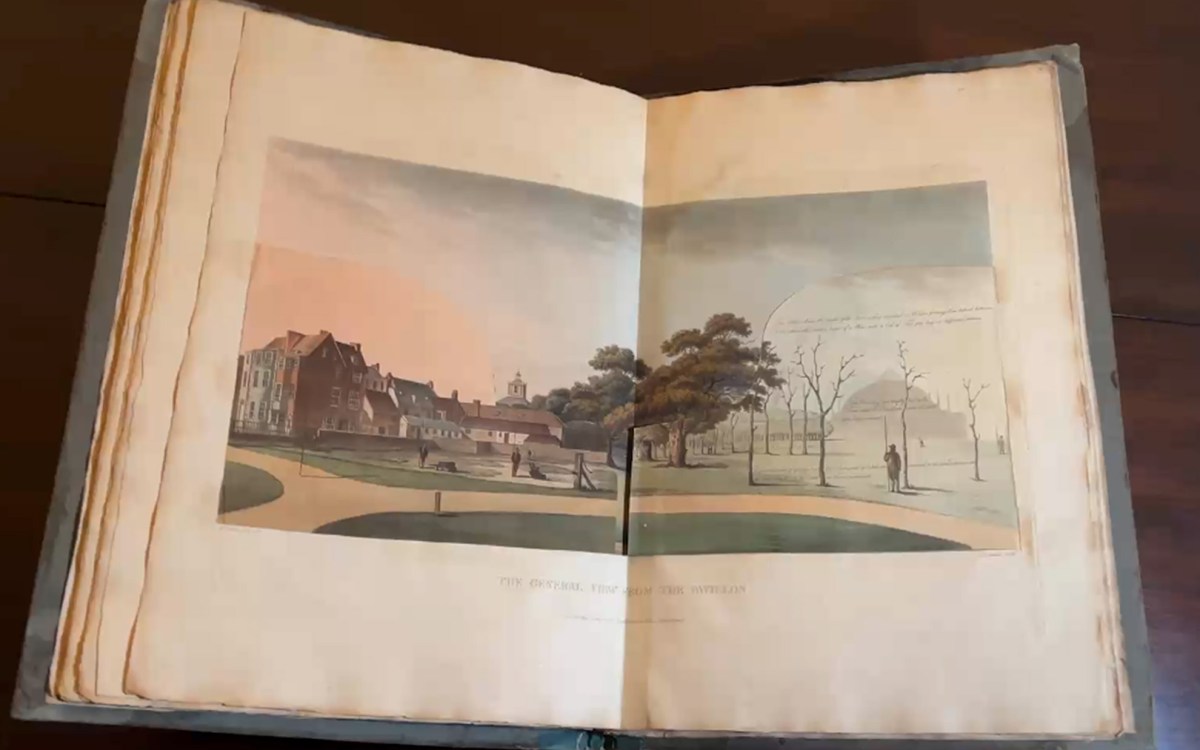

Maggie Zier ’16 turned her senior thesis about anti-lynching plays into a live performance at Harvard Law School. Elizabeth Cook (center), a Ph.D. candidate at Northeastern University, participated in the performance.

Photo by Lolita Parker Jr.

In anti-lynching plays, a coiled power

A devotee of history and theater, Maggie Zier ’16 restaged long-ignored works to acclaim

Many Harvard students can pinpoint a transformational moment — often a class or professor — that changed their experience at Harvard. For Magdalene “Maggie” Zier ’16, it was a book.

Zier discovered that book, Koritha Mitchell’s “Living with Lynching: African American Lynching Plays, Performance, and Citizenship, 1890–1930,” as a sophomore while taking Professor of African and African American Studies and of Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Robin Bernstein’s seminar “African American Theater, Drama, and Performance.” The book is a study of plays on lynching, a topic that proved so powerful and profound that three years later Zier wrote her senior thesis on three of the plays.

“It was the intersection of history and literature and theater, and this seemed to connect for me,” said the now 21-year-old Quincy House resident. “They have been discussed a little by scholars, but they deserve more attention as a window into black women’s creative contribution to this important social movement.”

The connection was natural for Zier, who arrived at Harvard intending to concentrate in history and literature.

“I grew up in Greenwich Village in New York City, and my parents encouraged me to study the humanities,” she said.

Being raised in the Big Apple exposed her to Broadway, and though she laughs at her own talents — “I’m a terrible performer” — she transitioned in college to behind-the-scenes roles, working as stage manager, producer, publicist, and costumer on shows such as “Assassins,” “Little Murders,” and “The Pillowman.” She became president of the Harvard-Radcliffe Dramatic Club her junior year.

In academics, Zier focused on African-American theater, but the anti-lynching plays, originally created by women to raise awareness and a sense of community among African-Americans living amid the horror, were foremost in her thoughts.

With research funding from the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History, and the Harvard College Research Program, she spent the summer before senior year in the library archives at Howard and Emory universities, researching the three plays — Mary Burrill’s “Aftermath” (1919), Georgia Douglas Johnson’s “A Sunday Morning in the South” (1925), and May Miller’s “Nails and Thorns” (1933) — that would become her senior thesis.

Last November, before the thesis was completed, she was invited to stage a reading of “A Sunday Morning in the South” at the Harvard Art Museums following a lecture called “The Visual Commons: #BlackLivesMatter” given by New York University Professor Nicholas Mirzoeff.

“Many people said they didn’t realize [the play] was from 1925. They thought it was 2015. The themes are so eerily relevant they couldn’t pinpoint when it was from,” said Zier, who was recently awarded a Hoopes Prize from the College as well as History and Literature’s Oliver-Dabney Award and the Department of African and African American Studies’ Elizabeth Maguire Memorial Prize.

The museum performance whet her appetite to continue to stage the plays, and Zier reached out to the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School (HLS), where Managing Director David J. Harris was eager to incorporate art into social justice programming.

“It was an easy sell for us,” said Harris. “That these plays were written by women, and the fact that women today are leading so many social movements, especially in communities of color — lots was compelling.”

Tapping her connections at the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.), Zier brought in Shira Milikowsky, the A.R.T.’s artistic associate, to collaborate with the institute, and her thesis adviser, Timothy McCarthy, history and literature professor and program director at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, which co-sponsored the event.

“There is a mandate across the University to collaborate, but it’s hard to get it done. This undergraduate goes out and arranges a meeting with the Law School and A.R.T. and [the Faculty of Arts and Sciences],” said Harris. “The amount of research she did, running around in pursuit of this project, shows a remarkable amount of determination. She exemplifies the absolute best of undergraduate education at Harvard.”

Held in the Ames Courtroom last month, the performance, “Plays That Don’t Play: The Drama of Lynching” featured the three plays performed by 14 students from the College, HLS, and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, as well as one student from Northeastern University. It was an evening (followed by a panel discussion the next day) that Harris described as “unbelievably powerful.”

“Everyone was riveted,” he said. “For a lot of people, Michael Brown’s body wasting on the street for four hours in the heat was evocative of lynching. These plays are terribly resonant.”

Zier, who will work as a W.E.B. Du Bois Public Policy Fellow at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Baltimore headquarters this summer, said the enthusiastic audience response is a testament to the power of theater to address material that is both historic and relevant in today’s society.

“To see them read aloud after all this time was moving. They’ve been pretty much left off stage,” she said. “I was trying to understand why playwriting would be the weapon of choice. I don’t have an answer, but it continuously intrigued me throughout the process.”