Pinning their hopes on buttons

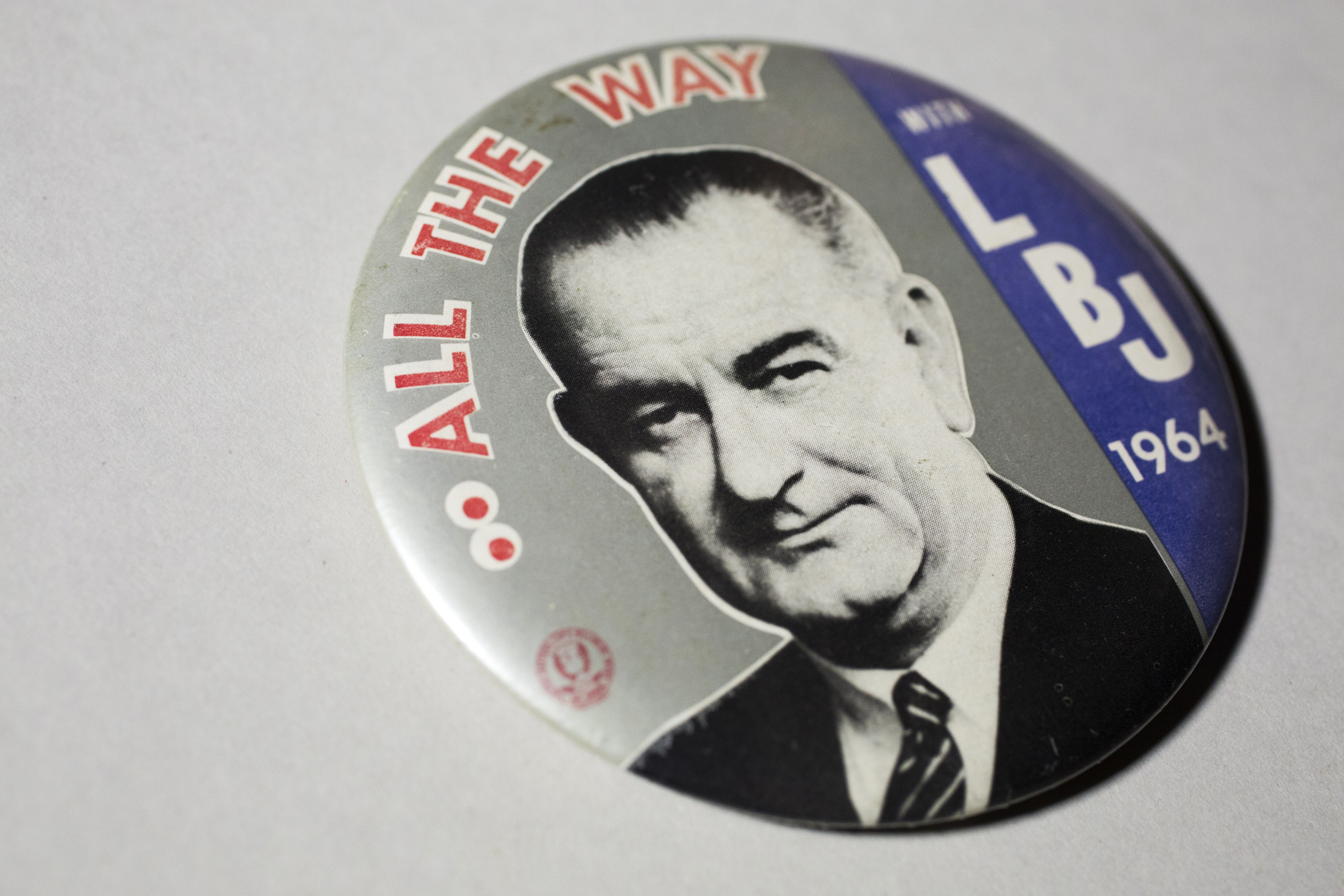

Lyndon B. Johnson 1964 campaign button.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Political buttons trace political and social change

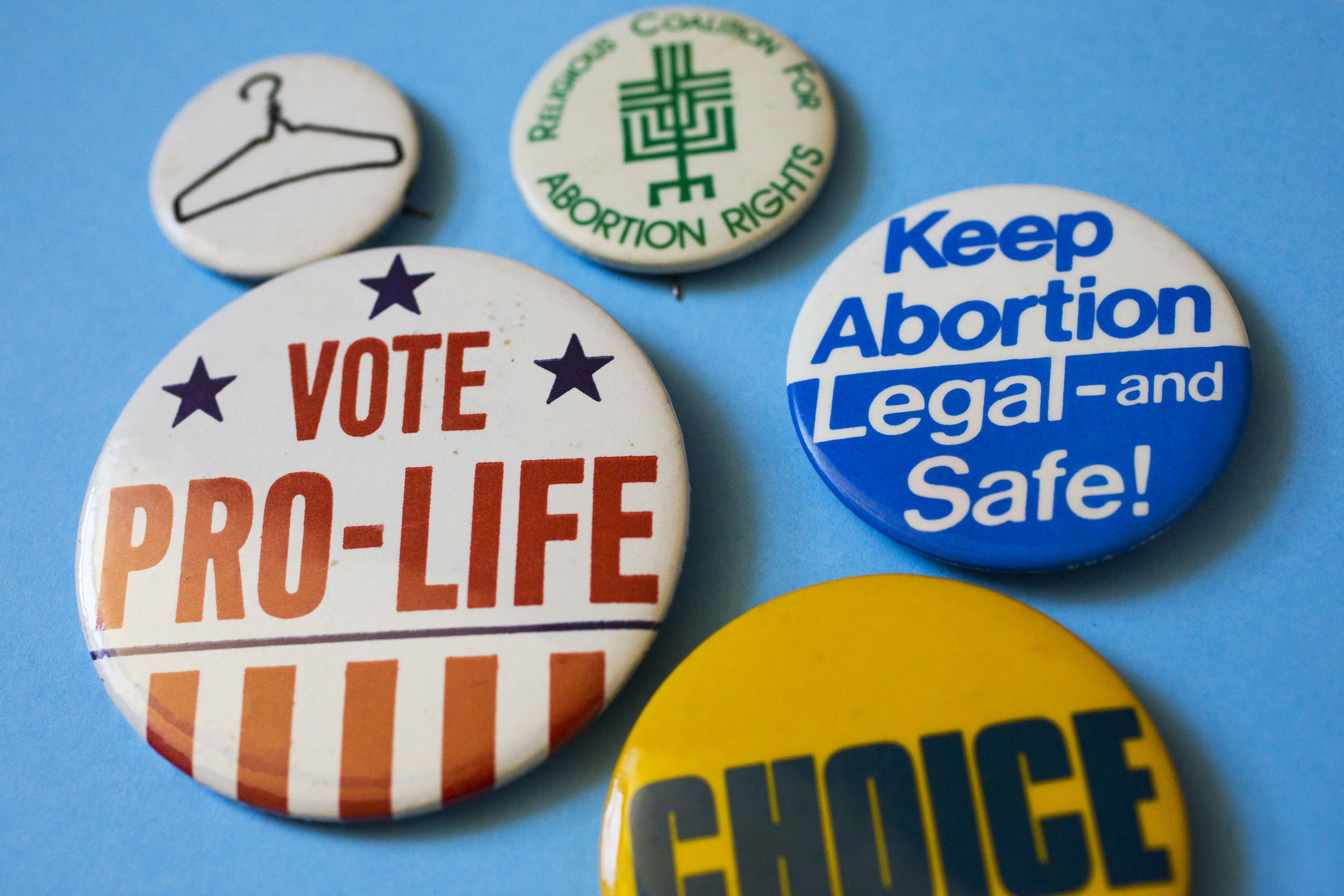

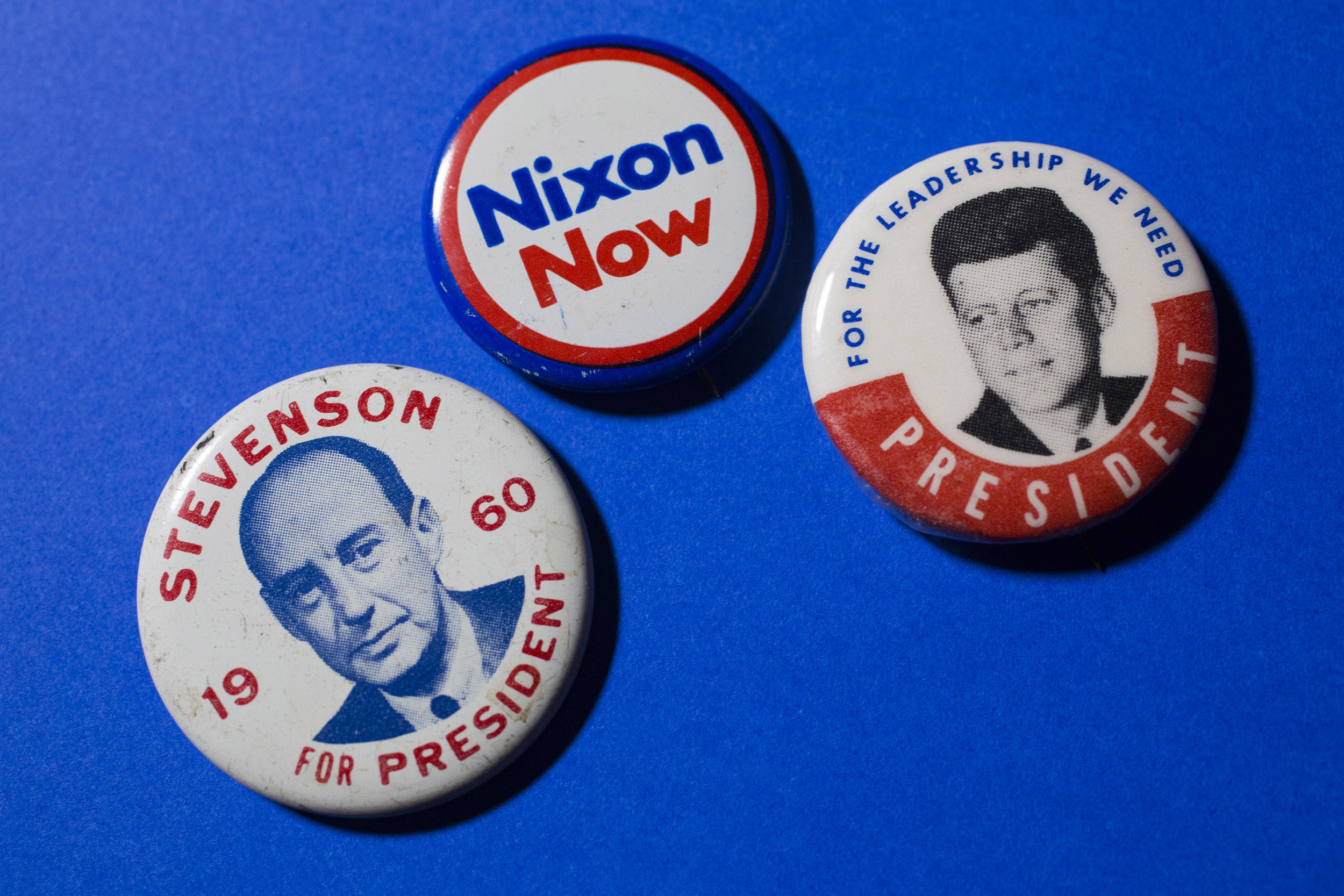

“All the way with LBJ.” “I like Ike.” Peace signs and rainbows. Catchy slogans, iconic symbols, and striking colors are the makings for memorable political buttons.

“Campaign buttons are ideal ‘collectibles’ because they are small, because they connect directly to events that can be dated and that often have very broad resonance, and because they remind us that ordinary people — voters and activists — drive political and social change,” said Laurel Ulrich, 300th Anniversary University professor and resident expert of objects at Harvard.

Schlesinger Library Curator of Manuscripts Kathryn Jacob has sorted through the Radcliffe Institute’s collection of nearly 1,000 buttons dating back to the mid-19th century. The buttons are from local elections, school committees and town councils, to state and national elections promoting the likes of Elizabeth Holtzman, a Radcliffe graduate and Congresswoman from New York, and Shirley Chisholm, the first African-American candidate to run for the presidency of the United States and the first woman to seek the democratic presidential nomination.

Campaign issues are wide-ranging, beginning with women’s suffrage and tracing the political movements that followed. The buttons “are very tangible representations of women in American culture and the role they have increasingly assumed during and after suffrage,” said Jacob. “I like the early suffrage buttons. I like to think of the women who were brave enough to wear them. It was a very big change in American culture. I like them for what they symbolize.”

The Harvard Kennedy School Library is home to about 2,000 buttons donated by Steven Rothstein, campaign enthusiast and former head of the Perkins School for the Blind. The collection traces ballot initiatives, topical issues, and local and national campaigns from Calvin Coolidge to Barack Obama.

For Director of Library & Knowledge Services Leslie Donnell, combing through the collection brought back many memories. “It’s very visceral,” she said. “For me, the excitement was to look back in time. I can remember campaigns that were going on in the ’70s. And it was really fun for me to look back and say, ‘I remember that.’”

Collectively, the buttons serve as an overview of American politics since the early 20th century. Individually, a button may bring back a particular moment in U.S. history.

“We have a number of Wallace buttons. I remember back in the late ’60s and early ’70s. I remember the trauma that was going on in the South. And so again, it brought back history, social history too,” said Donnell.

“Cronin for Congress.” “Maine for Muskie.” “Go Mo.” Alliteration and rhyme are tools of the button trade. Strong design may distinguish a button. And color is key. A bright orange Norman Mailer button stands out in a sea of blue and red tones, though course materials coordinator Emily Eckart, who has worked closely with the collection, is quick to point out, “He didn’t win.”

Interesting stories are unearthed from a button. McGovern/Shriver is the ticket most remember from 1972, but a couple of McGovern/Eagleton buttons found in the mix led Eckart to read about this lesser-known vice presidential candidate. Thomas Eagleton, who suffered from bouts of depression, had to quit the race when several hospitalizations were revealed.

For Eckart, while it is interesting to observe the trajectory of famous politicians through their rising offices, it’s even more fascinating to see the names from unsuccessful bids. “You never hear about them as soon as they lose, but it’s really cool to see how many people participated in the process.”