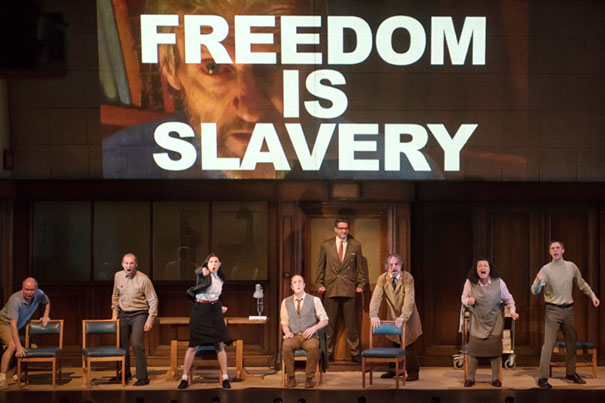

Orwell’s novel “1984” tapped into mid-century “fears about the combination of new technologies and authoritarian secretive politics, and how that is going to control thought and lives,” said Ash Center director Anthony Saich, who will lead a discussion on social media in China on March 2. The A.R.T.’s stage adaptation of “1984” runs through March 6.

Photo by Ben Gibbs

Ever-present Orwell

Themes of ‘1984’ remain a conversation starter

He was a member of his superstate’s single, ruling party. He worked in the government agency that controlled what information citizens could receive. But he grew disillusioned. Then, in secret, he began writing a book, knowing that to do so meant risking his own life.

That doesn’t only describe the protagonist in George Orwell’s dystopian novel “1984,” a stage adaptation of which is playing at the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) through March 6. It also describes the real-life Chinese journalist Yang Jisheng, who earned an award from Harvard’s Nieman Foundation for chronicling, in his book “Tombstone,” the full extent of the Communist regime’s culpability in China’s horrific famine of 1958-1962. Just last week, the Guardian reported that Yang has been barred from leaving China to receive his award in Cambridge.

Such cases show that the questions raised by “1984” remain as relevant as ever in the 21st century, said Ash Center director Anthony Saich, an expert on Chinese politics who studied in China in 1976 and has traveled to the country every year since. The Ash Center is co-sponsoring, with the A.R.T., a series of discussions on “topics that spark out of ‘1984,’” Saich said. The series, “Talk Back,” launched this week with a discussion on cybersecurity led by James Waldo, Harvard’s chief technical officer.

Orwell’s novel tapped into mid-century “fears about the combination of new technologies and authoritarian secretive politics, and how that is going to control thought and lives,” said Saich, who will lead a discussion on social media in China on March 2. “What’s intriguing about bringing ‘1984’ back now is that some of those questions are out there again.”

GAZETTE: Can you talk about how a regime revises history? For example, you’ve said that the Chinese leader Xi Jinping has “striven to render history in such a way that the party is the natural inheritor of Chinese tradition, a wild cry from the days of the Cultural Revolution.” How so?

SAICH: There is no doubt that the Chinese Communist Party has always sought to control the narrative for its nation. And to stop alternative narratives from emerging. That does not mean, of course, that the narrative stays the same over time. Mao Zedong told a story to legitimize the Chinese Communist Party that linked the broad sweep of history — the humiliation after the Opium War, the foreigners dismembering China. He talks about semi-feudalism, semi-colonialism. And he portrays the Chinese Communist Party as the natural outcome of that. But it’s as a radical rupture with China’s past: “We are the new.” In fact, there’s a slogan, “Without the Chinese Communist Party, there would be no New China.” So when I was first a student in China during the Cultural Revolution, Confucius was criticized, the traditions were criticized.

Now, though, we see as the Communist Party’s striving for a new legitimacy, it’s telling another story — that “unlike the Nationalist Party [which fled to Taiwan in 1949], we are the natural inheritors of all that was good in the Chinese tradition.” So they are now trying to draw a different line to the past.

And language becomes very important in this, the use of words and the way things are continually reframed and told. That’s where you see the linkage into “1984.” Now, I’m not saying by any stretch of the imagination that China is like the world in “1984.” But there are very conscious and clear efforts to control the narrative, to make sure it’s the one that the Chinese Communist Party wants. And that also underpins the revival of nationalism as a core value for the party. The belief in Marxism, Leninism erodes, so some kind of Confucianism, the Chinese tradition, and nationalism become important legitimators moving forward.

GAZETTE: Are people in China noticing the shift, and just not discussing it publicly?

SAICH: Well, what is quite clear is that a lot of traditional China never went away in Mao’s period. The fact that, so quickly, clans, temples, traditional religious practices revived in the countryside and even in the urban areas, meant that probably these were going on all throughout the Maoist period.

Now, of course, the way the party wants to use the tradition is more toward the obedience, filial piety, “You’re a screw in the big cog and know your place and listen to your elders and don’t stick out.” Those kinds of interpretations of it. That leaves out the right-to-rebel side. It’s kind of a caricature of Confucianism.

GAZETTE: Can you touch on the Internet and social media? They’re helping to spread awareness of dissident views, yet is the government using the same technology to clamp down on dissent?

SAICH: The answer is both, obviously. Any system that tries to control language opens itself up for ridicule. There used to be the “Big Red Joke Book” — jokes making fun of bureaucracy in Soviet Russia. I often use them in China, and just replace “Russia” with “China,” and people think they’re just as hilarious. So people will always make fun of their official slogans; they’ll twist them around, they’ll pervert the original meanings.

Now, if you put into that mix social media, does it open a new discursive space? Well, it does, but not as much as you would think. It means that memes and playfulness expand. And it has at different times meant that pressure is put on the government to act in a certain way.

But the government itself has become smarter. The government pays people 50 cents to put pro-government comments on social media. And they’re ridiculed as “the 50-cent party.” So that leads to its own sort of ridicule. But they’ve gotten much cleverer about restricting the capacity of new social media to spread disruptive messages quickly.

Because fundamentally, social media challenges the traditional idea of information flows in China as a vertical structure — information goes up, information goes down. New social media cuts across that, horizontally, and it moves fast. So yes, the government can block messages, it can pull things down, but usually the messages get out at least to some limited extent before they’re shut down. So in a way, it’s always playing catch-up. But that said, it’s gotten much more sophisticated about its control over the last three to four years.

GAZETTE: Control taking the form of censorship?

SAICH: It’s doing a range of things. It’s blocking: yes, censorship. It’s scrubbing, immediately, something comes up they don’t like. It’s also new regulations, for example requiring real-name registration to use the Internet. It’s also brought in legislation that if some “defamatory” message they feel is incorrect is retweeted more than 500 times, it’s a criminal act and you can be punished for it.

GAZETTE: About the use of language, what’s an example of Newspeak in China?

SAICH: In China, privatization is a dirty word. So there are lots of euphemisms — “mixed ownership,” “diversified ownership,” “collective enterprises” which are really private. Certain words become taboo, and then you find substitutes.

GAZETTE: Are there whole segments of the country unaware of criticism of the government?

SAICH: You’ve got a very sophisticated urban middle class, who are basically wired, and I think the Communist Party should trust them. They’re not going to rebel because they read this or that negative thing about the party.

But a lot of people basically use the Internet the same way they use it here — gaming, online shopping, watching shows, and so on. So I think a lot of people still tend to get their information from official sources.

And I can give you one example: I was in a small town in central China, a year or so after the student demonstrations in 1989. The official line was that it was a “counter-revolutionary rebellion.” People in Beijing, who’d witnessed it, many of them just called it “June Fourth,” some called it the “Beijing Massacre,” others called it “the Big Chaos.” So I was in central China, visiting some people there who were considered wacky liberals in this small town they lived in. And somehow the topic came up, and I used the phrase “the Big Chaos.” And they said, “Whoa — why do you say that? The party said it was a counter-revolutionary rebellion. We saw it on the television news and in the People’s Daily.”

And that made me really rethink, because these were sophisticated people, for the town they lived in. But of course, it didn’t happen in their town, far away.

GAZETTE: Would those same people now have more access to information, because of the Internet?

SAICH: Well, they do. But of course the Internet is heavily controlled. When I stay on the campus of Tsinghua University, one of the top two universities of China, I basically can’t get access easily to Internet from outside of China.

It’s interesting — I was in a hotel where foreigners stay, and in my room I was watching BBC, CNN. Then I went down to the gym, which is open to the public. No BBC and CNN. Same with newspapers. When the newspaper’s delivered to my room, I get it complete, even if, say, there’s a negative article about China in the International Herald-Tribune. If I go down to the bookstore in the same hotel, that page is taken out.

GAZETTE: They print a different edition? Or it’s just torn out?

SAICH: Just ripped out. Someone goes through it, and the command comes down, “Take this out.”

GAZETTE: With economic reforms since 1978, have things improved for many Chinese politically or socially since you first visited in 1976?

SAICH: When I was first a student there: No freedom of choice of job — work was allocated to you, it could be anywhere in the country. No freedom of movement — you couldn’t get a passport overseas as an individual. Even control over who you married — that was often politically determined. Files and dossiers on when you could or could not have a child. Holidays would be regulated through your workplace. Basically very little entertainment, very few restaurants. Everybody wore a blue Mao suit or a green Mao suit. If women had fancy haircuts, they’d be dragged out to have their hair cut.

So in that sense, if I were a young person growing up in China, I would have just seen endless expansion of personal and other freedoms. Now, you make your own choices about what you wear, your hair. You can get your own jobs, you can get an individual passport, you can study in America, you can choose where you go on holiday, you can choose whom you marry. Still restrictions about the number of children and when you can have them, that’s still there. But you can choose belief. You can choose to be a Buddhist, a Daoist, a Catholic.

So I can clearly imagine why a young Chinese person would think, “Why are these foreigners criticizing us? My life has just gotten continually better!” Now, that’s not true for every person and every category in China. But for people going to college, for the upwardly mobile middle class, they’re earning more, they’re buying their own apartments, which you couldn’t do before; they’re buying their own cars.

And I don’t know how many people want to read foreign news in China. How many people in America want to read The Guardian, China Daily? I’m not sure. It’s not relevant to their lives.

The thing is, here we can. That’s the distinction.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.