Patrick Randall plays “Smorball,” a video game created with the purpose of helping to transcribe handwritten files into digital and searchable text.

Photos by Jeffrey Blackwell

A playful turn for libraries

Crowd of gamers helps expand access to handwritten documents

More like this

William Brewster was 14 when he started chronicling the habitat of birds and wildlife in Cambridge. He went on to document the changing natural landscape of his hometown for more than 50 years from the late 1800s into the 1900s.

Brewster’s work, part of the collection at Harvard’s Ernst Mayr Library of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, represents an important resource in the study of the region’s natural history. One big problem, however, comes with transcribing the volumes of handwritten observations into digital text files that can be accessed and mined online.

A new initiative is underway to use gaming and crowdsourcing to speed the massive task of transcribing such documents, at Harvard and around the world.

The project, funded by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, enlists video gamers to help correct digital transcripts not easily converted into clean text files. Purposeful Gaming is a collaborative effort among the Missouri Botanical Garden, the Ernst Mayr Library, the New York Botanical Garden at Cornell University, and other members of an archives consortium called the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

“What we hope is that people with an interest in games — but who want to do something useful as well — will find these games to be the perfect answer,” said Ernst Mayr librarian Constance Rinaldo. “People who love beautiful books and are fascinated by early scientific exploration, natural history, and games have an opportunity to help improve discovery of concepts in handwritten notes and other documents that are difficult to automatically transcribe.”

The process under study is an alternative to optical character recognition (OCR), which converts images of text into encoded text files. OCR works well with uniform printed text, but less so with handwritten documents and certain typefaces.

Ernst Mayr was chosen to be a partner in the grant because it was one of the first libraries in the consortium to digitize field notes and diaries. About a dozen volumes of Brewster’s diaries were used to test the effectiveness of the games.

“Running these handwritten notes through optical character recognition is almost useless because it does not pick up the characters, and so it cannot be converted into text files reliably,” said Joseph deVeer, head of technical services in the Museum of Comparative Zoology. “In a nutshell, the Purposeful Gaming project was designed to feed multiple transcriptions through the game where players try to reconcile and determine which version is more accurate.”

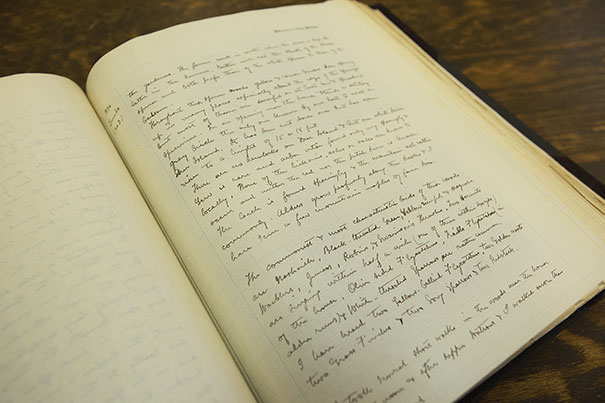

William Brewster’s field notes dated June 20, 1896. A single page stands among his field notes and manuscripts from the late 1800s and early 1900s, all located at the Ernst Mayr Library of the Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Photos by Jeffrey Blackwell

Dartmouth College’s Tiltfactor, a digital design studio and research laboratory, created two video games for the project.

The first, Smorball, resembles video football. Players can earn points by typing in words or phrases that pop up on the screen before they are tackled by the opposition. Beanstalk is a slower-paced game in which correct answers make the beanstalk grow.

Through each game, players are helping to interpret and transcribe the scanned pages of Brewster’s work. For each word or phrase, a minimum of four players must provide an interpretation before the game software begins looking for matches and consensus in the answers.

“The way it settles on one interpretation is when there have been at least four entries and one interpretation accounts for at least 75 percent of those entries, so it is based on consensus from the players about any word,” said Patrick Randall, the outreach coordinator at Harvard for Purposeful Gaming and the Biodiversity Heritage Library. “When enough people have picked an interpretation, the game will tag that word as complete. Once all the words for a single page of text have been tagged as complete, that text will be removed from the game.”

The games have a diverse group of followers, from people connected to the Biodiversity Heritage Library community to those interested in citizen science to gamers just looking for a new challenge.

In the fall, Tiltfactor brought Smorball and Beanstalk to the Boston Festival of Indie Games. In one day, a stream of players corrected more than 10,000 words on two laptops. Smorball was named the best serious game at the festival.

Mary Flanagan, founder and director of Tiltfactor Laboratory and the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor in Digital Humanities at Dartmouth College, said that the success of the games, in accuracy and popularity, should be an eye-opener.

“There’s a great future to engaging the public with games that support cultural heritage,” said Flanagan. “That said, I think that this type of engagement and outreach has to be an integral mission for institutions, and they need to market such engagement opportunities just as they would an exhibition or special collection. I believe that these early projects provide proof of concept and promise in order for institutions to take that leap.”

Library staffers at Harvard also see the potential for using gaming and crowdsourcing to widen access to old, handwritten documents and other challenging materials.

For example, William Brewster’s records contain a wealth of data about climate, bird diversity, and habitat changes. The Ernst Mayr Library holds 45 years of Brewster’s journals, field notes, and manuscripts, and just one volume may number 450 pages. A trained transcriber would spend nearly 15 minutes typing each page into a text file.

“With the project, 12 Brewster volumes were completed in less than a year,” said Randall. “Had those tools not been available and we just had library staff working on it — for one thing, we would not have been able to do that — but even if we did, it would take several years.”