The path to profits in Africa

Continent’s richest man describes how business can succeed there despite obstacles

When Aliko Dangote was building his business, running four cement trucks in Nigeria in the late 1970s, a relative gave him $750,000 to expand. Business was booming — there was a cement shortage — but instead of investing the money in the business, he gave it back.

“I was scared, as a small entrepreneur, to lose his money. So I returned it back to him,” Dangote said.

Dangote didn’t know it then, but he would have been a safe bet for the loan.

After decades of building up his cement business and expanding into sugar, flour, oil, and other commodities, Dangote today is worth $18.6 billion, making him Africa’s wealthiest man and among the world’s richest.

But success didn’t come easily. Speaking in the Charles Hotel at an event sponsored by Harvard’s Center for African Studies, Dangote described some of the difficulties an entrepreneur faces in Africa: unreliable infrastructure, traveling obstacles, corrupt governments. But each had an eventual solution, aided by dogged determination. To solve energy problems, for example, factories had their own power supplies.

“Investing in Africa is not easy. It’s very profitable, but very challenging,” Dangote said.

For years, Dangote said, he would go into work dreading the unanticipated problems he was sure to face. But he eventually made his peace with them, realizing that such problems came with the territory and that he’d deal with each in its time, rather than fretting about them before they even arrived.

“I developed a thick skin. In the environment where we operate, there will be problems every single day,” Dangote said.

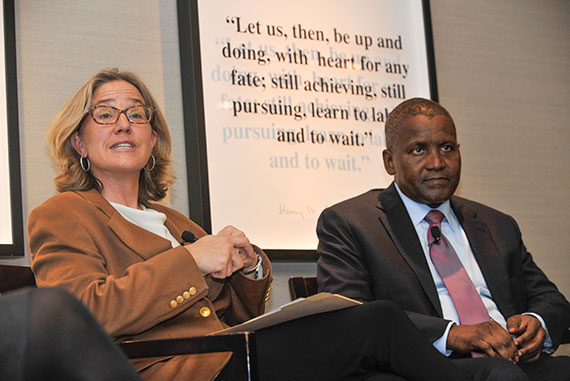

The president and chief executive officer of the Dangote Group delivered the Center for African Studies’ inaugural Hakeem and Myma Belo-Osagie Distinguished African Business and Entrepreneurship Lecture Thursday evening. Dangote was introduced by Caroline Elkins, Oppenheimer Faculty Director of the Center, professor of history and of African and African-American Studies. Dangote was joined by Hakeem and Myma Belo-Osagie who, together with Elkins, asked questions.

In her introduction, Elkins said that Dangote has been a change agent for Nigeria and for Africa more broadly, and she predicted that his impact on the continent will one day be understood to be similar to that of industrialist John D. Rockefeller and computer innovator Steve Jobs in the United States.

The Dangote Group is large enough that it makes up about 30 percent of the market capitalization of the entire Nigerian stock exchange, Elkins said, and the company’s plans would take it from a $24 billion to a $120 billion company by 2020. Dangote has also created one of the world’s largest charitable foundations, endowing it with $1.25 billion.

Dangote’s winding path to success included an aborted venture into telecom and the collapse of a textile business in the face of competition from Chinese and Indian manufacturers, which forced the layoff of 6,400 workers.

Dangote offered his sometimes-humorous take on his years as an entrepreneur in Africa before a standing-room crowd of nearly 200 who packed the meeting room. He gave listeners insight into the business environment in Africa — sometimes difficult, but with opportunities — and into his own journey.

In response to a question about how thoroughly new ventures were planned, Dangote said he and his executives were always concerned about theft of their ideas, so business plans were drafted by a small group and closely held. Even the plans presented to banks in pursuit of financing were only 75 percent complete, in case they were stolen and sold to competitors, he said.

Despite the ups and downs, his businesses were successful enough to finance themselves until 2000, the year he first borrowed to finance expansion.

Financing could be hard to come by. He and his team struggled to finance construction of a $480 million cement plant, which would be Africa’s largest. They borrowed what they could from smaller Nigerian banks, which could not afford to loan the full amount. They got some 90-day, short-term notes with interest rates up to 42 percent, he said. Luckily, at the time, the sugar business was up and profitable, which provided more capital.

“So, we were borrowing short-term money to finance long-term investment, which was very, very … creative,” Dangote said to laughs. “We knew we were able to keep pushing and we would do it one day.”

Eventually, Dangote said, he and his team were able to cobble together the necessary financing for a seven-year, $479 million loan from a consortium of 13 lenders. Meanwhile, the plant’s construction went badly off track. They had to build a 92-kilometer gas pipeline, a dam, and hundreds of houses for workers. The project wound up costing $1.2 billion, of which $200 million was interest payments.

The perseverance paid off. The business was almost immediately profitable and, within 18 months of opening, Dangote and others were able to pay off the loan, he said.

Along the way, Dangote was open to help. He asked advice from the chairman of Heineken early on and conferred with consultants from Arthur Andersen and McKinsey & Co. at key points in the business’ growth. Though he called government corruption the biggest problem in Africa, he joked Thursday that he had some sway with military governments because they were actually afraid of businessmen, who might finance the next coup.

Dangote called for reforms to ease the way for African businesses. Cross-border travel, he said, should be made easier. As a Nigerian, he has to get visas ahead of time to travel to many African countries, while British or American travelers can just get them on arrival, for example. Trade between African countries should also be increased, he said, adding that nations that import goods rather than producing their own are hurting their people.

“You are importing poverty into your country and exporting jobs out,” Dangote said.