Doctors in a hard place

Increasingly, report says, they can face criminal charges for tending alleged terrorists

Doctors who provide medical assistance to people labeled terrorists are increasingly vulnerable to prosecution in the United States and other Western democracies, according to a law briefing by the Harvard Law School Program on International Law and Armed Conflict (PILAC).

The 236-page report highlights the prosecution of an American physician who offered to work as an “on-call” doctor for wounded members of al-Qaida in Saudi Arabia. The report also details the prosecution of a Peruvian doctor who cared for members of the Shining Path guerrillas, and of a physician who provided medical and surgical services to insurgents in Colombia.

The cases underscore the effects the global war on terror can have on the international humanitarian law that protects doctors who tend enemy combatants from punishment or prosecution.

Released earlier in September, this is the first comprehensive report to examine how counterterrorist policies threaten to erode international humanitarian law protecting medical care for wounded combatants in armed conflicts.

Those safeguards have been around since the establishment of the Red Cross in 1863, said Gabriella Blum, one of the report’s authors and the Rita E. Hauser Professor of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law at Harvard Law School.

But the new report’s authors contend that the law has been weakened by the war on terror and the United Nations Security Council’s antiterrorist directives.

“The whole raison d’etre behind the establishment of the ICRC [International Committee of the Red Cross] was to make sure that those who are injured and no longer fighting are not left without medical treatment,” said Blum. “This is the fundamental principle we should focus on.

“And the fact that you then label that person a terrorist, at that moment, it shouldn’t matter,” she said. “At the time he’s injured and is in need of medical care, it doesn’t — at least, it shouldn’t — matter.”

Blum, who is also the PILAC faculty director, co-authored the report with Dustin Lewis, program senior researcher, and Naz K. Modirzadeh, program director and lecturer on law.

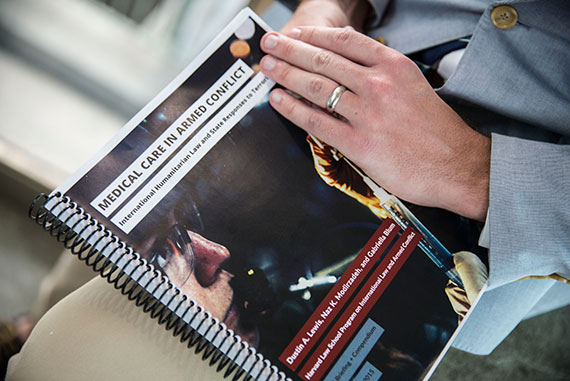

Titled “Medical Care in Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law and State Responses to Terrorism,” the report criticizes the U.N. Council, which in the late 1980s spearheaded the global war on terror.

The Security Council, the report says, moved without “due public consideration” in legislating global antiterrorism measures that contradict international humanitarian law. The council, for instance, requires member states to take action against terrorist threats but fails to demand that states exempt impartial wartime medical care even when such care may be protected under international humanitarian law.

The report says there are gaps in the law that allow states to make their own rules to fight terrorism. Also, international humanitarian law lacks protection for all aspects of medical care, and its measures are not universally applicable to all armed conflicts or followed by all countries.

“We’re left today with a somewhat fragmented normative landscape, where different countries have different obligations,” said Lewis. “Today, with few exceptions, the United States can prosecute any physician, whether she is American, French, or Somalian, who knowingly provides medical assistance to terrorists.”

Since 1949, when the First Geneva Convention ruled that no one could be convicted for having nursed the wounded or sick, regardless of his nationality or conduct, no major directive addressing protections for medical care in the war on terror has been issued.

For the authors, there is an urgent need for a ruling in favor of impartial medical care for all of the wounded and sick — military and civilians, terrorists and non-terrorists alike — in all armed conflicts.

It’s the right thing to do, they said, to preserve the foundational ethic of international humanitarian law, which places medical personnel above the conflict.

“We don’t expect readers to have a lot of sympathy to ISIS or al-Qaida,” said Blum. “What we’re concerned about is the erosion of the principle. We want people to make a value judgment on how dangerous a counterterrorism strategy is in potentially undermining a much broader ethical and legal commitment that goes way beyond the question of al-Qaida, or ISIS.”