Gary King, the Albert J. Weatherhead III University Professor, has co-authored a new study that uncovers flawed forecasts by the Social Security Administration. “Pretty much everybody who evaluates Social Security realizes there’s a problem … But the system is in significantly worse shape than their forecasts are indicating,” King said.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Uncertain forecast for Social Security

Program’s financial health has been overstated for years, studies say

A new study has found that the financial health of Social Security, the program that millions of Americans have relied on for decades as a crucial part of their income, has been dramatically overstated.

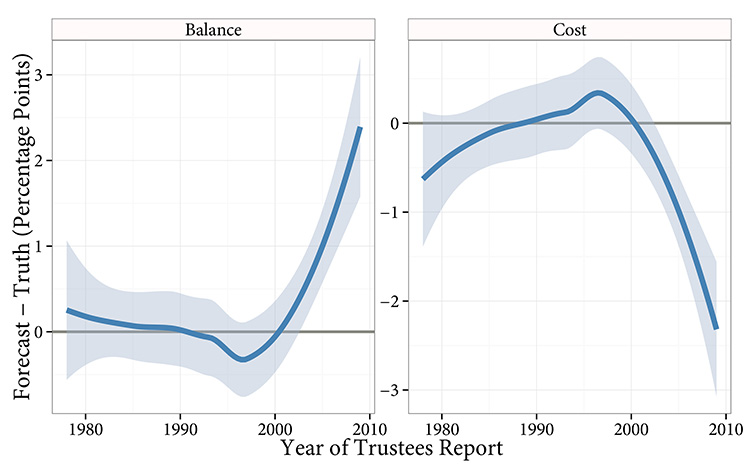

The study compared all forecasts made by the Social Security Administration over the 80-year history of the program with its actual outcome, and found that its forecasts of the health of Social Security trust funds have become increasingly biased since 2000. Current forecasts are likely off by billions of dollars, and the program could be insolvent earlier than expected unless legislators act, the study found.

The study, which appears Friday in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, was co-authored by Gary King, the Albert J. Weatherhead III University Professor at Harvard University; Konstantin Kashin, a Ph.D. student at Harvard’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science; and Samir Soneji, an assistant professor at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice.

In a second paper, published on the same day in Political Analysis, the Harvard-Dartmouth team points to antiquated, ad hoc methods for creating the forecasts as the cause for the growing bias. They suggest that otherwise laudable efforts to insulate the forecasts from political influence have resulted, somewhat ironically, in insulating the process from data that could improve their accuracy.

“The bias in their forecasts results in a picture that’s rosier than it really is,” King said. “They’re not saying the system is in good health. Pretty much everybody who evaluates Social Security realizes there’s a problem … But the system is in significantly worse shape than their forecasts are indicating.

“This is a major problem,” he continued. “Social Security is the single largest government program. It lifted an entire generation of elderly out of poverty, and today affects the lives of almost every American. The forecasts are essential for ensuring the solvency of the Social Security trust fund, as well for Medicare and Medicaid, which together add up to half of the entire budget of the federal government.”

While forecasting the health of the Social Security trust funds has long been part of the program — each year, the administration creates forecasts that look one, five, 10, 20, and even 75 years into the future — the study conducted by the Harvard-Dartmouth team is the first by anyone inside or outside of the government to evaluate their accuracy.

“It’s typically been difficult to conduct studies that evaluate forecasts, but the Social Security Administration has been around long enough that if they made a 10-year forecast a decade ago, by now we can look to see how they did,” Soneji said. “There’s tremendous scientific value in evaluating real-world forecasts that were made by people who were really trying to figure out what the future was going to be like.”

What they found, King said, was that while forecasts were never perfect, they were largely unbiased for quite some time.

“On average, they were about right until about 2000,” he said. “Sometimes they were too high, sometimes they were too low, but they were able to adjust quickly enough over time and remained fairly accurate.”

Over the last decade and a half, however, those course corrections weren’t made, and the gap between the forecasts and reality has grown steadily. To understand just how wide that gap is, King said, it’s necessary to understand the other key role played by Social Security auditors: evaluating legislation related to the program.

“For every major policy proposal that’s put forward by Democrats or Republicans, they do what’s called ‘scoring’ the proposal,” King said. “This is a tremendously valuable service, and they’re the only ones who do it. Unfortunately, because the actuaries making the forecasts do not share all their data and procedures, no one else can.”

But when King, Kashin, and Soneji collected every policy score from the past several decades and compared them to the forecasting bias, the result was troubling.

“Even if we assume that every one of those policy scores was 100 percent right for today, which is an unrealistically optimistic assumption, when we look at the uncertainty in their forecasts, we find it’s larger than almost all of the policy scores,” King said. “That’s hugely problematic, because it means all the policy debates about Social Security are being informed by something that’s basically random noise.”

While there is benefit to Democrats and Republicans coming together to debate how best to reform the Social Security system, King said the simple step of making the data used in the forecasts public would dramatically improve them, and provide the parties with a more solid foundation upon which to have that debate.

“No one else can make fully independent forecasts of Social Security because they have the data, and they don’t fully share it with anyone,” King said. “They don’t share it with government; they don’t share it with academics; they don’t even share it with other parts of the Social Security Administration. There’s no reason it needs to be kept secret … And if they were to make the data available to the scientific community, academics would fall over themselves competing to help them make better forecasts, and ultimately that would be better for absolutely everyone in the United States.”

While the evidence points to increasing bias in the forecasts produced by the Social Security Administration, it still begs the question of why the forecasts have been skewed in one direction versus another.

Ironically, King said, it may be the result of Social Security auditors doing just what the public might want them to do and insulating themselves from the contentious political questions that swirl around the program.

“One thing that has happened since 2000 is that people started living longer than expected, which means people are drawing benefits longer than expected,” King said. “But in trying to hunker down and insulate themselves from the politics, they ended up insulating themselves from the data as well.”

Among the keys to improving the forecasts, King said, will be bringing the forecasting process into the 21st century.

“They’ve been using almost the same methods to generate these forecasts, with few important changes, since the program was instituted,” Soneji explained. “They have committees that try to set some of the parameters for their models, but there is a great deal of informality and a lot of ad hoc decisions. It is an essentially a qualitative process that could be formalized.”

In the wider world, the revolution in big data, data science, and statistical methodology of the past several decades has deeply transformed how forecasts are generated, yet relatively little of that progress has been utilized by the Social Security Administration. Ideally, King said, the process should be automated where possible, with humans stepping in when they can add value. As it stands today, with many people making hundreds of informal decisions, the process is rife with procedures that social psychologists have demonstrated can lead to inadvertent biases, no matter how hard individuals try to avoid them.

To avoid such problems, King said, the Social Security Administration needs to do two things: develop a formalized, replicable approach to generating forecasts that automates the process as much as possible; and work with social psychologists and other experts to ensure that, when humans do enter the process, their inherent biases are controlled as much as possible.

“For example, one thing they do is forecast mortality rates by age,” King said. “We know that mortality rates are lower for a 60-year-old than an 80-year-old. But that’s just one of 200-plus parameters they have to consider in these forecasts. One person can’t remember what those 200 parameters are, much less what their relationships are, all at the same time.

“The approach we have now may have been the best method decades ago. But now we have much better methods of automating, not 100 percent of the process, but far more of it. We don’t want quantitative methods to replace human decision-making; we want them to empower human efforts. Similarly, there’s no reason to add up a long column of numbers without a computer these days, but your computer isn’t going to know what column to add up without you in control.”

No matter what reforms are put in place, King said, it’s important to understand that the forecasting process will never be foolproof.

“The progress that’s been made in data science formalizing, and thus improving, human decision-making has been spectacular, and these developments need to get to Social Security,” King said. “The rest should be dealt with by social psychologists, who can devise procedures to take the human bias out of the process that must remain qualitative. For example, the late Harvard psychologist Richard Hackman showed that if men and women auditioned for violin spots in an orchestra from behind a curtain, men still won most of the spots. But if you took off their shoes first, so the judges couldn’t hear who had on high heels, the gender bias vanished.”

Soneji explained: “The combination of modern data science, modern social psychology, and modern data sharing can vastly improve the situation.”

Ultimately, however, taking steps to improve the forecasts can’t keep Social Security from becoming insolvent. The debate over how to keep the program afloat must be left to the nation’s elected representatives. But by improving the forecasting process, King said, it is possible to ensure that debate is informed by facts.

“I don’t know how the politics are going to come out,” King said. “There certainly are ways to keep the system from going insolvent: You could slightly lengthen the retirement age, increase taxes on the wealthy, or increase payroll taxes. Our results don’t say which of those to choose, or even whether to choose anything. I think the politicians will do something. There have been grand compromises over Social Security over the years. When the parties sit down to negotiate, all we want is for them to have the real facts. That’s all.”