The talented Georges Doriot

Exhibit portrays rich career of father of venture capital, legendary HBS professor, and military innovator

“If I were a speculator, the question of return would apply. But I don’t consider a speculator — in my definition of the word — constructive. I am building men and companies.” — Georges F. Doriot in “General Doriot’s Dream Factory,” Fortune, August, 1967

On the surface, Georges F. Doriot was a bit of a contradiction: a proud Frenchman who became a naturalized U.S. citizen to join the Army in World War II; a lifelong academic who formed the first public venture-capital firm and had great success bringing together industry and science; and a Harvard Business School (HBS) student who never graduated but became one of the School’s most memorable and influential faculty members over a 40-year career.

But to those who knew him, Doriot, who died in 1987, was an iconoclast, a maker of men whose multifaceted career as a professor, military leader, innovative venture capitalist, and founder of Europe’s first modern M.B.A. program made perfect sense. To be successful, one needed to master every aspect of business, from raw materials and good ideas to the global marketplace, while always keeping an eye on the horizon.

A remarkable story

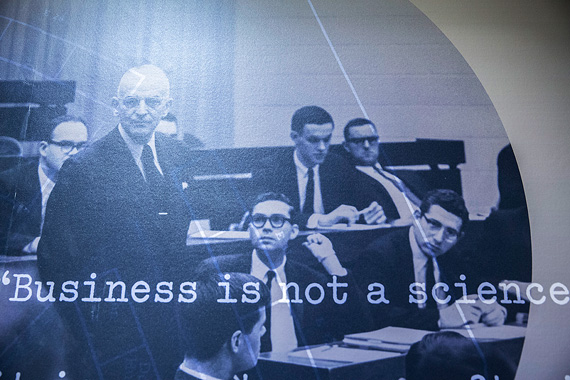

1.011415_Doriot_031.jpg

The Baker Library is home to the Georges F. Doriet Collection through August. Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

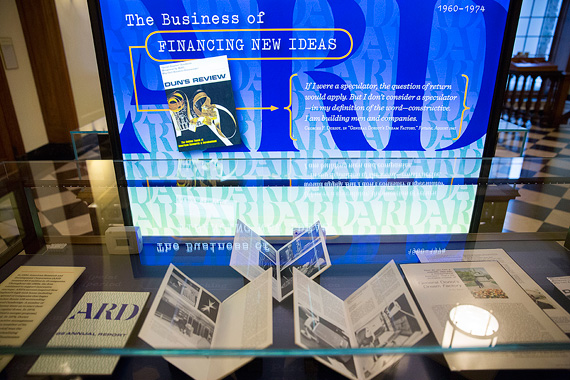

2.011415_Doriot_028.jpg

Over the span of 40 years, Doriot taught nearly 7,000 students at Harvard Business School.

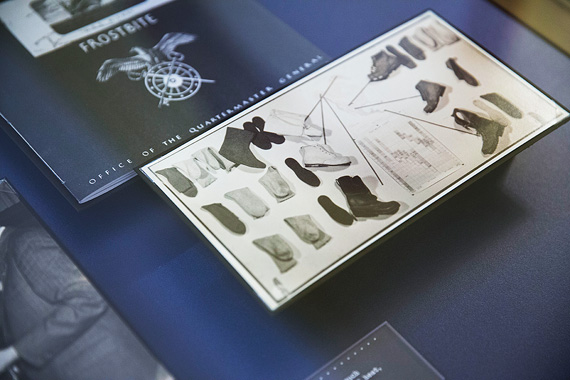

3.011415_Doriot_010.jpg

Laura Linard, director of special collections at the Baker Library, shows the various platforms used to view the Georges F. Doriet Collection.

4.011415_Doriot_012.jpg

The Baker Library exhibit was filled with manuscripts, artifacts, and photographs that captured Doriot’s storied career in venture capitalism and education.

5.011415_Doriot_023.jpg

In 1942, as chief of the Research and Development Branch of the Military Planning Division, Doriot oversaw the production of wartime products such as cold weather combat boots and water-repellent socks.

“The arc of Doriot’s life — his extraordinary contributions as both an educator and as one of the founders of the modern venture-capital industry — is linked in many ways to the story of the postwar entrepreneurial economy,” said Melissa Banta, guest curator of a vivid exhibition on Doriot’s life and career on display now through Aug. 3 at the Baker Library. “It was a great reflection in terms of all the things that happened with the American economy, as well as the history of business education in this country.”

Born in France in 1899, Doriot was the son of an automobile engineer for what would later become Peugeot Motor Co. A 1920 graduate of the University of Paris, he came to Cambridge the following year intending to study management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), but instead was persuaded by Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell to come to HBS. After a year, Doriot left to take an investment banking post in New York City, but returned to HBS in 1925 as an assistant dean and, for the next four decades, as an inspirational professor of industrial management.

Doriot taught the misleadingly named “Manufacturing,” a popular but notoriously difficult, yearlong course that teased and tested the executive and general management skills of second-year M.B.A. students through memorable, if controversial, lectures; rigorous teamwork out in the field; and completion of sweeping, analytical reports that often ran 600 pages or more.

“When I look back at him, he was the person who most shaped me at the School,” said Warren McFarlan ’59, M.B.A. ’61, the Baker Foundation Professor and Albert H. Gordon Professor of Business Administration Emeritus at HBS. “It was his vision, it was the ability to force us out into the field in a meaningful way and capture our imagination, that we could do something bigger than we thought we were able to do beforehand.

“And his lectures — the ideas just still sort of ring in my mind today,” he added. “I would not be on the faculty except for the fact that he inspired me to do things in a different kind of a way.”

The course, which ran from 1926 until Doriot’s compulsory retirement in 1966, counted thousands of students, including some of HBS’ most high-profile graduates of the era, known as “Doriot Men,” such as Philip Caldwell (Ford Motor Co.), John Diebold (the Diebold Group), Ralph Hoagland (CVS), Dan Lufkin (Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette), and James D. Robinson III (American Express).

“He personifies the impact that a faculty member can have, not only as a really inspirational teacher and mentor … but also the impact that he had in terms of industry itself, the whole creation of the public venture-capital industry. And then, finally, the impact that he had in terms of business education in Europe,” said Laura Linard, the Baker Library’s director of special collections.

The exhibit debuts numerous books, brochures, magazines, documents, and other artifacts from HBS’ own vast collection, as well as many on permanent loan to the Baker Library from what is now the French Cultural Center in Boston. Doriot and his wife, Edna, who met at HBS, each served for many years as the French Library’s president, bringing it to national prominence for its fostering French-American cultural relations.

A commanding presence, Doriot was known as “The General” long after his service in the U.S. Army during World War II. He retired as a brigadier general in 1945, earning the Distinguished Service Medal and honored as a Commander of the British Empire and with the French Legion of Honor.

Doriot oversaw research and development in the Office of the Quartermaster General. Tapping his industrial and scientific connections, he proved adept at identifying new products and inventions to save the Army time, money, and raw materials, and he encouraged companies such as Ford, General Motors, Monsanto, and Dow Chemical to develop commodities to fulfill the urgent needs of combat troops in the field. Water-repellent fabrics, L.L. Bean boots, cold-weather socks, body armor, backpacks, sunscreen, insecticides, Saran wrap, and K-rations were among the wartime innovations introduced during Doriot’s tenure.

“He had a strong affinity toward technology and the notion that what you [have] today isn’t going to be around 20 years from now,” said McFarlan.

Returning to HBS, Doriot founded the American Research and Development Corp. (ARD) in 1946, widely regarded as the first venture-capital firm open to public investors, with Doriot among the first to see venture capital as an industry. One of ARD’s early successes came in 1957 when engineer Kenneth Olsen, a U.S. Navy veteran studying at MIT and working at MIT’s Lincoln Labs, and his partner, Harlan Anderson, sought seed money for a startup venture called Digital Equipment Corp. to provide businesses with computers that were smaller and less expensive than the IBM and Univac mainframes of the day.

The fledgling firm’s original four-page typewritten business proposal to ARD would soon net Digital $70,000 in equity financing for a 70 percent stake and a $30,000 loan. By 1961, ARD had invested $3.6 million in 18 companies and was the first venture-capital firm with shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

Seeing business’s global future in the 1920s, and the need to prepare leaders for its arrival, Doriot helped found one of Europe’s first business-management programs, the Centre de Perfectionnement aux Affaires (CPA) in Paris. The center, a successful collaboration among Doriot, HBS, and the Paris Chamber of Commerce, would open the doors for the 1957 launch of the Institut Européen d’Administration des Affaires (INSEAD), an international graduate school of business administration modeled after HBS and started by one of Doriot’s former students.

Doriot’s desire to help entrepreneurs get their ideas off the ground, but in a responsible, forward-thinking way, is a lasting and noteworthy contribution to the American economy, said Banta

“Doriot emphasized that, to him, the point of venture capital was not to make a quick profit, but rather to support entrepreneurs with good ideas and to help emerging technologies and startups succeed for the long term,” she said. “The ways in which he taught and practiced these ideals offer a valuable history lesson.”

The exhibit continues through Aug. 3 at the Baker Library, Bloomberg Center, Harvard Business School.