Making a case for democracy

Sandel will address British Parliament, which is celebrating its 750th anniversary

The terrorist attacks in Paris on the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo and a kosher supermarket by a group angered by cartoon images of the prophet Muhammad have put a fundamental pillar of democracy — freedom of speech or expression ― under harsh new threat and heightened scrutiny.

Is all speech equally valid? What are the limits of free speech? And how do governments and citizens safeguard free speech, particularly when confronted by extreme anti-democratic views?

Those kinds of questions, and many others, will no doubt steep the heady atmosphere inside the Palace of Westminster next week when Harvard Professor Michael Sandel brings his dynamic oratorical style to Britain’s Parliament for an unprecedented dialogue with British MPs, peers, and citizens on the meaning of democracy and why it seemingly so often falls short in various societies today.

“The whole idea is to prompt the members of Parliament and members of the public to engage in a lively discussion about what democracy means, what justifies democracy, really, and if it is the best form of government — or the least-bad form of government — why is there so much unhappiness with the way democracy is working today?” said Sandel, the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Government at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, in a phone interview.

A renowned political philosopher, Sandel is best known for teaching “Justice,” one of the University’s most enduring and popular undergraduate courses, which challenges students to consider essential questions about democracy, ethics, and justice.

Sandel’s talk is a special edition of his ongoing “Public Philosopher” lectures for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) and will air Jan. 20 as part of its “Democracy Day” programming. It will be the first time the BBC has been permitted to broadcast an event of this kind from inside Parliament, a spokeswoman said.

“Tuesday, the 20th of January, is the 750th anniversary of what is widely recognized as England’s first Parliament, no better time to consider the past, present, and future of democracy in the U.K. and around the world,” Peter Hanington, editor of the BBC’s “Democracy Day,” wrote in an email.

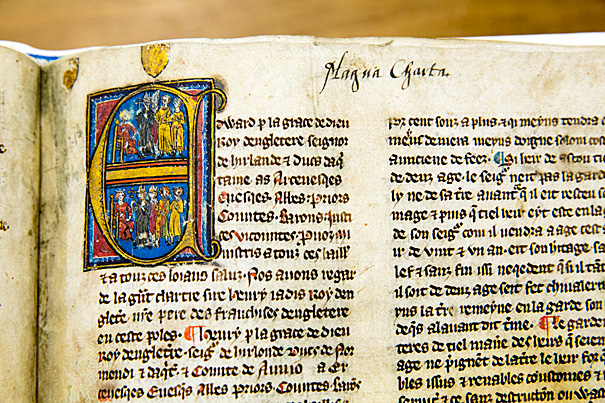

The “Democracy Day” events are part of a broader, yearlong series of debates and events organized by the BBC called “Taking Liberties” that celebrate the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta, the foundational English political text that codified the basic human rights and democratic principles that underpin the U.S. Constitution, as well as representative democratic governments and legal systems around the world.

Sandel said his goal in giving public lectures about complex political and philosophical issues like democracy in grand cultural venues such as the Sydney Opera House and great institutions like Parliament is “to try to elevate the terms of public discourse, to offer a model of what reasoned public discourse about justice and the common good, what it means to be a citizen, and what reasoned public discourse about ethics and values might be.

“I travel around the world, and I’m struck by the widespread frustration in democracies around the world with politics, with politicians, and with political parties. There seems to be a deep and widespread frustration, a loss of trust in democratic institutions. And I think one of the reasons for this is the terms of public discourse are largely empty and impoverished,” he said.

“What passes for political discourse these days consists of either narrow, managerial, technocratic talk, which inspires no one, or, when passion does enter, we have shouting matches — highly partisan, often bitter shouting matches where politicians and elected officials and citizens are shouting past one another rather than engaging seriously with the big, ethical questions, questions about justice and the common good that should be at stake in democratic public discourse,” said Sandel.

“So I think part of the challenge is to recover the lost art of democratic discourse and to find a way to discuss with civility and respect some of the big and sometimes controversial moral questions that citizens care about. People want politics to be about big things. And too often the most important questions — especially questions about values — don’t really find their way into reasoned, public discourse.”

Given current world events and with the U.K. parliamentary election slated for early May, Sandel said he hopes to get the assembled politicians “to go beyond the partisan politics of the day and to reflect together about what democracy is really for.”

“Because these days, there’s a growing gap between what citizens seem to want from their democratic institutions and what politicians are delivering. I’m hoping that we’ll find away to move beyond the familiar talking points.”