Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library exhibition “What They Wrote, What They Saved: The Personal Civil War” kicked off its opening in November with remarks from Harvard President Drew Faust, the Lincoln Professor of History.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The personal Civil War

Schlesinger Library exhibit explores the conflict’s intimate, individual narratives

Civil War scholarship is often about the very large: histories told, battles recounted, politics analyzed. But an exhibit at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study’s Schlesinger Library makes the war small, a window into the lives of some of those caught in the nation’s bloodiest conflict.

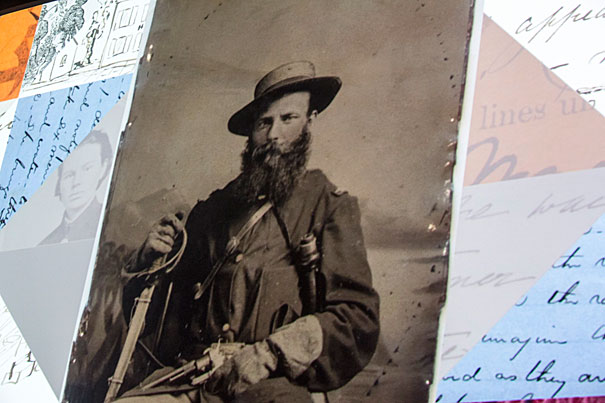

“What They Wrote, What They Saved: The Personal Civil War” includes eight glass cases of diaries, correspondence, books, photographs, and other artifacts from Union soldiers and their families. Together they paint a private picture of grief, grit, heartbreak, and hope.

“You won’t find much here about politics or the execution of the war,” said Kathy Jacob, the Johanna-Maria Frænkel Curator of Manuscripts, who helped search the Schlesinger collections for show items. “It’s really about families and how the war touched lives and what soldiers were missing when they thought of home.”

Largely absent is a Southern perspective, added Jacob. The exhibit is drawn almost entirely from middle- to upper-class Northern families, she said. “This is really what our Civil War collections are richest in.”

The small exhibition runs through March 20 and offers visitors an intimate glimpse into soldiers’ lives. The letters describe simple moments such as camp chores, or mending socks; some include whimsical drawings of camp quarters.

On May 19, 1862, Royal Pierce Barry, a major in the 4th Iowa Cavalry stationed in New Bern, N.C., penned a letter to his future wife, Eleanor “Nell” Marria Jones, describing the plants he encountered on a hike. He enclosed a handful of seeds he found on his travels. “What they are,” Barry wrote, “I do not know.”

Other correspondence shed light on war’s bitter truths. In a letter to his wife, also from May 1862, Benjamin Rector wrote of captured Confederate soldiers held at his camp for execution, and of the anguished visits from the men’s families. “The cries of wife and children,” wrote Rector, “haunt us almost day and night.”

In some letters and diaries, mothers and sisters struggle to cope with life at home on their own, and confess their fears for sons and brothers in military service. Those fears were realized in a telegram announcing the death of Col. Lewis Weld. The young soldier, like more than half of those who died during the war, succumbed to disease and not to wounds.

The somber note offered his family some finality. Many worried relatives weren’t so lucky.

“Desperate families both North and South traveled by the hundreds to battlefields to search in person for missing kin,” wrote Harvard President Drew Faust in her award-winning book “This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War” (2010). “Observers described railroad junctions crowded with frantic relatives in pursuit of information about loved ones.”

Faust’s own work on the Civil War period has relied heavily on firsthand accounts and archival materials. The Schlesinger collection, she said, shifts scholarship on the war from the experiences of generals and statesmen to those of ordinary soldiers, women, and slaves.

Such a collection, said Faust during the show’s November opening, “is fundamental to our understanding of the Civil War.”

Highlighting the library’s rich holdings from the Beecher Stowe Collection is a case full of ephemera related to the life and work of the famous abolitionist and author Harriet Beecher Stowe. A letter from the social reformer and abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison to Stowe in 1862 tells of a black preacher from Maryland imprisoned for five years for “the shocking offense of having a copy of ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ in his house.”

In the same case is a first edition of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Life Among the Lowly.” Many historians believe that Stowe’s best-selling novel to some extent changed American views of slavery and energized the abolition movement. Nearby is a copy of “The Life of Josiah Henson,” the memoir of a former slave that Stowe said helped to inspire her character Uncle Tom.

Memorabilia from the roles that women played in the war fill out another case. Thousands worked as nurses; others went South to teach freed slaves during and after the war; many others volunteered for aid organizations. The only woman to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor, Mary Edwards Walker, was a battlefield surgeon. In a photo taken years after the war, she stands proudly, the medal pinned to her coat.

Some women played dangerous roles in the Civil War, in one of the most curious chapters in the private lives of common soldiers. Exact numbers are unknown, but scholars estimate that hundreds of women on both sides fought as men. The Schlesinger exhibit includes a copy of “Nurse and Spy in the Union Army” by Sara Emma Edmonds, who fought in disguise as soldier Frank Flint Thompson. The book was an instant hit, selling close to 200,000 copies.

Next to the book is a photo of Frances Hook, a.k.a. Frank Miller. Hook, pictured in uniform and sporting cropped hair, signed up with her brother in the early days of the war with an Illinois regiment. She was wounded, caught, imprisoned, and discharged, but repeatedly re-enlisted.

“If a woman decided to do this,” said Jacob, “she was usually pretty determined.”