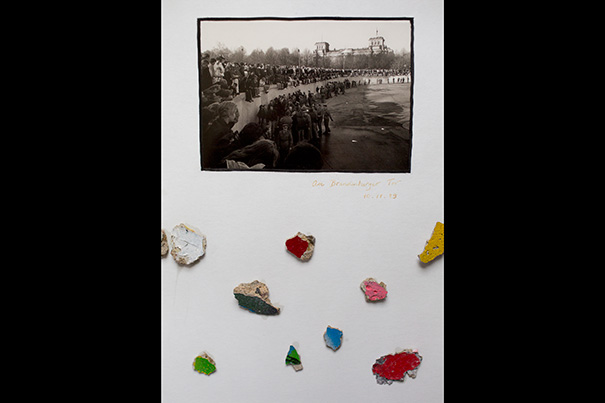

In the office of Carl H. Pforzheimer University Professor Robert Darnton hangs a framed postcard featuring a crowd dancing on the Berlin Wall. His teenaged daughter is included in the image. Darnton also added small fragments of the wall in the display.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

When the wall came down

Scholars recall scenes in Berlin before and after

It was the most enduring symbol of the Cold War and communist oppression, an imposing concrete wall with large sections wrapped in barbed wire and lined with attack dogs and border guards. Between 1961 and 1989, more than 100 people were killed trying to escape the East German regime for a better life in the west.

Twenty-five years ago this Sunday, a wave of forces crashed up against the Berlin Wall and broke it open, transforming Germany and history. Those forces, as well as the celebration they gathered toward — days and nights of joyous Berliners dancing atop the divide — remain particularly sharp in the minds of three Harvard scholars.

Historian Robert Darnton was a fellow at the Institute of Advanced Study in West Berlin in 1989. Author Mary Elise Sarotte ’88 had just returned to the United States from a year of study at the University of West Berlin. Waltraud Schelkle, a native German, was living in the city and working in developmental economics.

Darnton, Harvard’s Carl H. Pforzheimer University Professor, had intended to write a monograph on 18th-century France. Then “the ground began to tremble,” he said, and so he quickly changed course, directing his gaze to the shifting political landscape.

Signs of change came in the form of press reports about the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s call for greater openness and transparency. But there were other telling signs, too. While attending an academic conference in East Berlin in the summer of 1989, Darnton was nudged by an excited colleague after a speaker cited the work of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, considered taboo by East German officials. Soon after, Darnton’s friend nudged him again.

“He said, ‘Did you see that? He wasn’t talking from a script.’”

Lectures had to be read from prepared scripts cleared by the local cell of the communist party, Darnton recalled. “Something really big is going on,” his friend told him.

Darnton, who vividly captured his experiences in “Berlin Journal, 1989-1990,” was at times a firsthand witness to unrest. Traveling to East Germany, he attended protests and rallies. But on Nov. 9, when the wall finally fell, he was out of the country. “The irony is, and this pains me to admit it, I was not there … I was in Rome giving a paper.”

Back in Berlin a few days later, Darnton was the first person to escort a different friend, a scholar from East Germany, on his inaugural tour of West Berlin. The reaction was striking.

“I remember asking him, ‘What words would you find to convey your first impressions?’ and what he said was, ‘It’s so ugly,’ which really took me by surprise. But what he meant was all this neon, all these advertisements, all of this consumer society flaunting itself at him, as he felt. Whereas in East Berlin … none of that existed. There were, as in many East German cities, huge slogans on top of buildings — not exactly advertising, but giving you sort of communist hortatory about working harder for the party and that kind of thing. But aside from that there was really nothing, no neon that I could remember and very few lights.”

On New Year’s Day, Darnton found himself celebrating among hundreds atop a section of the wall near the Reichstag. “We just climbed on. You weren’t supposed to do this, but it was complete chaos. The only way you could get up was someone would extend an arm and pull you up and then you were absorbed into this sort of peristaltic movement of people on top, as though you were in the intestines of something. It was an extraordinary experience.”

The Accidental Fall of the Berlin Wall | PolicyCast

Sarotte’s extraordinary experience in Germany happened the year before the wall came down. A recent Harvard graduate, she was considering law school or a career in medicine until her transformative time in East and West Berlin set her on a path to history.

“I lived there that year and I was a historian, that was that. I wanted to understand what was going on, I wanted to understand causes. And I haven’t looked back.”

Sarotte, a professor at the University of Southern California who is visiting professor in both history and government at Harvard, immediately began the process of collecting information about that pivotal year. The research eventually became her most recent book: “The Collapse: The Accidental Opening of the Berlin Wall.”

Sarotte said she was eager to highlight the “middle actors” involved in helping topple the wall, people “not featured in the histories.” Those actors included disaffected border guards on duty that night, mid-level bureaucrats, and members of the dissident groups who were peacefully pushing for change.

Two of the dissidents interviewed by Sarotte, Uwe Schwabe and Siegbert Schefke, visited Harvard’s Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies recently to discuss their involvement with the protest movements. What is often forgotten, said Sarotte during the discussion, was that a protest march in the East Berlin town of Leipzig, organized with the help of Schwabe and captured by Schefke in a film that was smuggled to the West, was key to helping open the wall a month later.

Schwabe described the situation in the street on Oct. 9, 1989, when 100,000 protesters marched around the ring road in Leipzig chanting “join us” to soldiers, many of whom put down their weapons and did. The marchers didn’t know how it would end. Many, worried about a Tiananmen Square-like event, had left instructions and powers of attorney with family and friends about “who should take care of their children if they didn’t come back,” recalled Schwabe.

While it was Gorbachev’s policies that set the parameters and provided the context in which the wall could open, said Sarotte, “that didn’t actually become the actual opening of the wall. It was the local catalysts on the ground who made that happen.”

Schelkle, a visiting scholar at the Center for European Studies, had moved to West Berlin in 1981. Eight years later she was starting her first job after college. Like many longtime residents of the city, the barrier was something she said she “took for granted.” It wasn’t “oppressive,” she recalled, “just inconvenient.”

The decisive moment was followed by a long-lasting “good feeling” in the streets, Schelkle recalled — people were friendlier, more likely to say hello. But perhaps most resonant, she said, was an experience she had at the wall not long before it fell. A friend from the United States had come to visit sometime in 1987 or 1988; she took him to see the Reichstag.

“This ruin stood right on the border. The Wall was less than four meters high, and there were platforms which we could climb to look onto the other side,” wrote Schelkle in a piece for the London School of Economics, where she is an associate professor. “My friend, a middle-aged academic, had heard and read enough about it to have formed a mental image of its dimensions. But as we walked towards the Reichstag, he turned to me and exclaimed, incredulously: ‘What, this is the Wall?’ He had anticipated it to be a much more monumental construction; after all, it managed to divide a continent. I remember my surprise at his surprise. But on second thoughts, he had a point: it was not the rather shallow pre-cast slabs of concrete that made it so impenetrable. It was that many on the Eastern side defended it and many on the Western side got used to it.”