Revolutionary thinker

Professor’s revisionist study focuses on Parliament

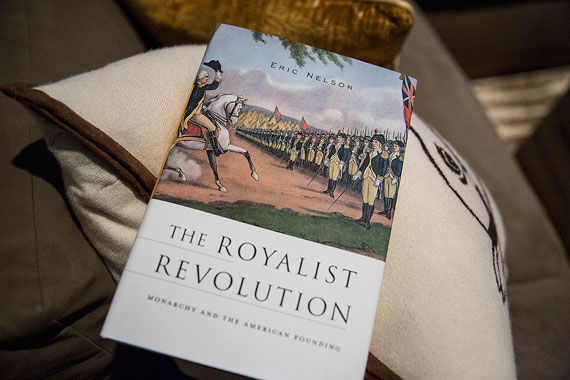

In his new book, “The Royalist Revolution: Monarchy and the American Founding,” Robert M. Beren Professor of Government Eric Nelson focuses on abuses of the British Parliament, rather than the actions of the crown, as the central force behind the Revolution. The Gazette spoke with Nelson about 18th-century politics, executive power, and more.

GAZETTE: This is a pretty revolutionary book (pun intended). What was the catalyst for writing it?

NELSON: A group of undergraduates came to my office hours in 2008 to complain that there was no course at Harvard on the American Revolution. My initial response was: “Look harder!” But it turned out that they were right. This seemed unfortunate to me, not least because my office is about 400 yards away from the spot where Washington mustered the Continental Army in July 1775. So I decided to put together a course on the political thought of the Revolution. The topic had always fascinated me, and I had written about it in a cursory way in my first book, but it took a good deal of work to bring myself up to speed. As I read my way through the pamphlet literature of the period in detail, I began to see the story of the Revolution quite differently.

GAZETTE: Isn’t it weird that the Founding Fathers would want to give more control to one figure? That’s typically called a dictatorship these days.

NELSON: This is bound to seem decidedly odd to us, since we are so used to understanding the Revolution as a revolt against kingly power and executive tyranny. But seen from the perspective of a British American in, say, 1770, it’s entirely unsurprising. Patriots confronted what they regarded as a tyrannical legislature (i.e., the British Parliament) that was claiming the right to tax them and legislate for them in numerous respects. They came to believe that Parliament could only be restrained by a re-energized crown, and they accordingly urged George III to revive prerogative powers that no English monarch had wielded for almost 100 years. I believe that this patriot turn to the royal prerogative is what set American constitutionalism on its distinctive path.

GAZETTE: How are the themes in this book modern and applicable today?

NELSON: The story I tell speaks directly to a number of present-day controversies, not least the current debate over the extent of executive power. Many critics of President Obama have explicitly grounded their opposition to his use of executive orders, recess appointments, and so on in a particular narrative about the origins of the American Revolution. To take just one example, in an essay endorsing congressional litigation against the president, George Will insisted that, “having rebelled against George III’s unfettered exercise of ‘royal prerogative,’” the Founding Fathers surely could never have intended to invest their new chief magistrate with the sorts of powers being claimed by the president. Now, the uses of executive power under discussion may or may not be constitutional (my own view is that some are and some are not), but this understanding of the Revolution is largely false — and it prevents us from forming a proper understanding of the place of the executive in our constitutional scheme.

GAZETTE: You recently had jury duty. Was it your first time? Can you tell me anything about the case and how it went?

NELSON: It was a difficult but fascinating experience. I’ve never had much time for the argument (often attributed, problematically, to Aristotle) that groups make better decisions than individual people, because they are able to harness the talents, observations, and experiences of each of their members. But I have to say that some version of this phenomenon was very much on display during our deliberations in the jury room. Almost every juror noticed something important about the case that no other juror had observed. So perhaps there is something to the so-called wisdom of crowds, at least under some circumstances.

GAZETTE: “The Royalist Revolution” is being called a revisionist history book. If you could go back and change something from your life, would you? What would it be, and why?

NELSON: When I was about 11 years old, I threw a temper tantrum that persuaded my parents to allow me to quit the piano. This was a huge mistake that I’ve always regretted.

GAZETTE: This is a staunchly academic book — no light beach reading here. Tell me something nonacademic about you that might surprise people.

NELSON: I’m quite a fanatical skier, but I suppose the least scholarly fact about me is that I’m a voracious consumer of bad television. After a day of research and teaching, I’m not the guy who curls up with a copy of Joyce. I need to shut my brain off, and I tend to do this by watching 1) anyone playing anyone else in football; 2) cooking competitions (even though I don’t cook); or 3) those awful shows about buying and fixing houses (even though I can barely change a light bulb). Sad, but true.