Imbalance in microbial population found in Crohn’s patients

Microbiome analysis reveals increase in pathogenic bacteria, drop in beneficial microbes

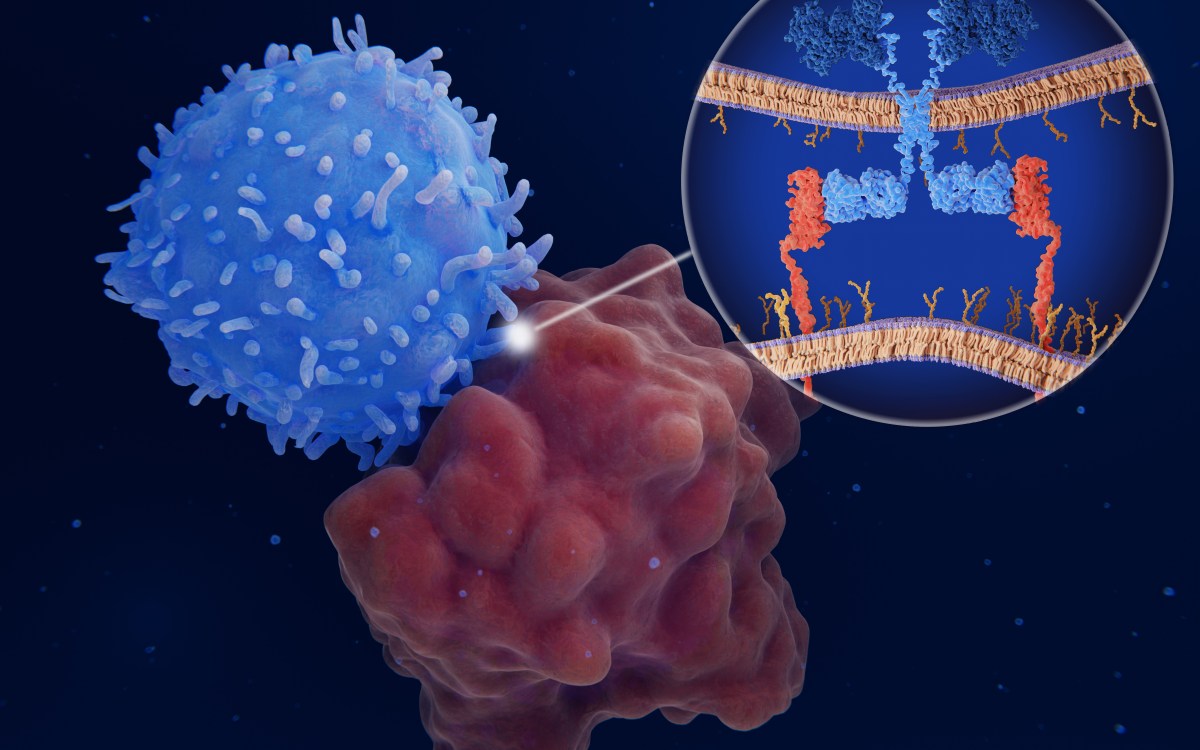

A multi-institutional study led by investigators from Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT reports that newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease patients show increased levels of harmful bacteria and reduced levels of the beneficial bacteria usually found in a healthy gastrointestinal tract.

In their paper in the March 12 issue of Cell Host & Microbe, researchers identified how the intestinal microbial population of the Crohn’s patients differed from that of individuals free of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Several studies have suggested that the excessive immune response that characterizes Crohn’s may be associated with an imbalance in the normal microbial population, but the exact relationship has not been clear. The current study analyzes data from the RISK Stratification Study, which was designed to investigate microbial, genetic, and other factors in a group of children newly diagnosed with Crohn’s or other inflammatory bowel diseases. At 28 participating centers in the United States and Canada, samples of intestinal tissues were taken from 447 participants with a clear diagnosis of Crohn’s and 221 control participants with noninflammatory gastrointestinal conditions. The researchers also analyzed samples from an additional group of about 800 participants in previous studies, for a total of more than 1,500 individuals.

Advanced sequencing of the microbiome — the genome of the entire microbial population — in tissue samples taken from sites at the beginning and the end of the large intestine revealed a significant decrease in diversity in the microbial population of the Crohn’s patients, who had yet to receive any treatment for their disease. The samples revealed an abnormal increase in the proportion of inflammatory organisms in Crohn’s patients and a drop in noninflammatory and beneficial species, compared with the control participants. The imbalance was even greater in patients whose symptoms were more severe and those who had markers of inflammatory activity in tissue samples.

“These results identifying the association of specific bacterial groups with Crohn’s disease provide opportunities to mine the Crohn’s disease-associated microbiome to develop diagnostics and therapeutic leads,” said senior author Ramnik Xavier, chief of the MGH gastrointestinal unit and director of the hospital’s Center for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

Other key findings of the study include:

- identifying the niches of specific microbial strains in Crohn’s disease and their effects on other microbial community members;

- finding that rectal biopsies can indicate the presence of disease early in the course of Crohn’s, regardless of which intestinal segments are affected; and

- showing that fecal samples collected at the onset of disease do not reflect changes in the bacterial communities of the intestinal lining.

Antibiotics are often prescribed for symptoms suggestive of Crohn’s before a diagnosis is made, but microbial imbalance was even more pronounced in participants who happened to be on antibiotics at the time samples were taken, suggesting that antibiotic use could actually exacerbate symptoms rather than relieve them, the authors note. Next steps will be to uncover the function of these microbes and their products and learn how the microbiome and microbial products interact with the patient’s immune system, with the possibility that these interactions could represent the molecular basis for the disease.

“Identifying which microbial products are key to disease onset and to inflammation resolution in inflammatory bowel disease and establishing which can be effectively targeted are our best hope to uncover the first microbiome-based therapies in IBD,” said Xavier, who is the Kurt J. Isselbacher Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Dirk Gevers of the Broad Institute is the lead author of the Cell Host & Microbe report. Curtis Huttenhower of the Broad Institute and Harvard School of Public Health is a co-author.