Maria Molteni (left, photo 1) and Hans Tutschku worked on the installation in Byerly Hall. Tutschku (photo 2) gave the exhibit a whimsical touch. “It’s a little machine, which reacts to people,” he said of the collection of antique cigar boxes stacked on top on each other. They emit sounds that are triggered by motion detectors when people walk by (photo 3).

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

A rich artistic stew

Radcliffe fellow, a composer, adds elements of dance, painting, and photography to build a textured exhibit

Hans Tutschku often can be found in his sound studio in Paine Hall, composing by using a complex system of computers, mixers, synthesizers, and turntables that meld traditional acoustic music with prerecorded sound.

But Tutschku’s diverse creative impulses reach well beyond the electroacoustic realm. Tutschku, who is Harvard’s Fanny P. Mason Professor of Music and director of Harvard’s Studio for Electroacoustic Composition, is indulging his fascination with the visual arts as part of a fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

“I am getting constantly this question of what my profession is, and I am constantly evading an answer,” said Tutschku, a child of musicians who was born and raised in East Germany, during an interview in the airy Byerly Hall gallery at Radcliffe. “Officially I am a composer, and that is probably what I am doing most. But I studied theater. I have done a lot with photography, with pottery — just trying to find outlets which allow me to express things I can’t express in the other mediums.”

Touch of Tutschku

“The Other Side” is a series of photographic installations, interactive sound sculptures, and performance videos. Images courtesy of Hans Tutschku

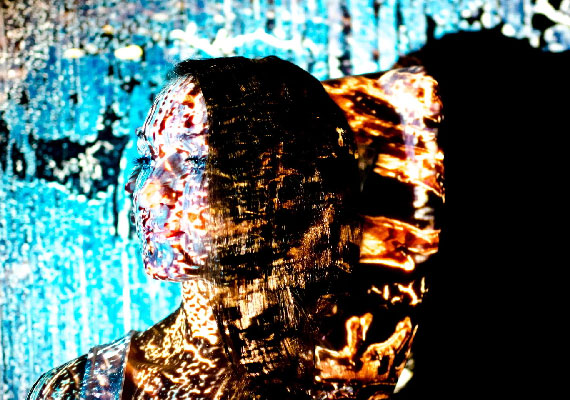

Part of the piece titled “Protected.”

A second part of “Protected.” There are 26 photos that constitute the bulk of the exhibit.

A section of the piece title “Separated.” Tutschku’s oil paintings were projected onto dancers on a stage.

Much of the show was developed in tandem with Harvard undergraduates. This piece is titled “Mourning.”

A second part of “Mourning.”

Though his main focus as Radcliffe’s 2013-2014 Rieman and Baketel Fellow for Music is a new composition for soprano voice, large ensemble, and electronics, Tutschku said that working in other mediums helps to “sharpen my senses to be as honest to my [other] plans as I can.”

To that end, he has embraced the institute’s philosophy that encourages fellows to explore other academic and artistic interests. “The Other Side,” which runs through March 28, is his whimsical and wistful series of photographic installations, interactive sound sculptures, and performance videos. Much of the show, which grew out of an earlier project based on his interest in painting, was developed in tandem with Harvard undergraduates.

He laughs when discussing his early attempts at oil painting. “Painting is a little far-fetched — it’s probably messing with paint,” he quipped on a recent afternoon as he methodically installed the 26 photos that constitute the bulk of the exhibit. But the painting results were “good enough,” he said, to keep going. Eventually, working with a music ensemble in Germany in the 1980s, he developed a multidimensional work, fusing sound with images of his oil paintings that were projected onto dancers on a stage. That work inspired his current project, a series of haunting images.

In need of a new set of collaborators, Tutschku turned to Jill Johnson, director of Harvard’s Office for the Arts Dance Program.

“It is marvelous for the students to be a part of this project,” said Johnson, who connected him with students from her Harvard Dance Project, a new, yearlong, faculty-led ensemble that focuses on performance research, collaboration, and choreographic composition, while linking choreographic thinking to other fields.

The exhibition, she said, “exemplifies the kind of trans-disciplinary opportunity for students this course aims to foster.”

For two days last fall, Tutschku worked intensively with students inside the program’s black box theater on Garden Street. He snapped photos of the dancers as they struck various poses, their bodies softly illuminated by the projected images of his paintings. The result is a series of evocative pictures that change depending on the viewer’s perspective.

At first glance, an image that looks like water rippling on a rocky shore, or a glittering shot of the galaxy, transforms into the face or the outstretched limb of a dancer upon closer inspection.

Tutschku, eager to make the process as collaborative as possible, hooked his camera to a computer. Dancers not involved in a particular scene gathered around the screen to watch their classmates and spontaneously shouted out suggestions for different poses and movements to those in front of the camera.

“There was this kind of vibe in the room which was much more than just I take a photo and probably in three weeks you can see it,” said Tutschku. “The kind of interactivity happening was amazing.”

Senior Rossi Walter, a dancer featured in several images in the show, said, “Each photo shoot was always accompanied by a chorus of ‘wow’ and ‘whoa’ as we saw the results.”

Other works in the exhibit include videos of similar multimedia pieces involving dancers moving oil paintings, done by Tutschku in 2007 and 2009, that are displayed on two iPads attached to a wall. There also are two whimsical, interactive sound sculptures.

“It’s a little machine, which reacts to people,” said Tutschku of the collection of antique cigar boxes stacked on top on each other. They emit sounds that are triggered by motion detectors when people walk by. On one side, several small, black computer fans whir against four electric guitar strings. Near the top, a high-pitched ringing comes from iPhone vibrators hitting the end of a pair of his grandmother’s wine glasses. Elsewhere, a voice repeats a nonsensical poem.

At the gallery entrance, his newest work, another series of stacked cigar boxes attached to a pillar, beckons passersby with several blinking yellow lights. With a simple wave, visitors become composers, as snippets of unaccompanied vocal music recorded by Tutschku during his travels — Scottish tunes, songs by Spanish fishermen, and Japanese or Jewish sung prayers — begin to play in pairings, depending on where the listener motions their hands.

A slender photo on the back of the pillar exposes the circuitry behind the music, revealing a series of microprocessors, wiring, loudspeakers, amplifiers, and power supplies.

The work partly reflects his youth. Growing up in communist East Germany, which was cut off from the West, Tutschku said he was “always looking to the other side and to all the other possibilities” that a free country might offer. “It’s also this kind of fascination with what is behind something.”

“The Other Side” will be on exhibit weekdays from 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. through March 28 in the first-floor gallery of Byerly Hall, 8 Garden St., Cambridge.