“The Hanging Gardens at Villa I Tatti” is among many Steve Ziger watercolors illustrating the oral history site (photo 1). Bernard Berenson, in 1903, stands in front of a favorite painting (photo 2). The Berenson library was a coveted refuge for visitors (photo 3).

Images courtesy of Villa I Tatti

Bernard Berenson, recalled

Oral history project at Villa I Tatti interviews last links to art historian who donated Renaissance center

In the fall of 1884, a slender teenager dressed in a worn suit walked into Harvard Yard. The transfer student from Boston University was Bernard Berenson, a son of a Boston tin peddler and a future world-famous art historian and connoisseur.

Entering Harvard gave the former Bernhard Valvrojenski, who was probably the first Russian Jew admitted to the College, “a status he coveted,” one scholar wrote. It was place where he could immerse himself in studying ancient and romance languages, witness a world just awakening to the organized study of art history, and feel the liberating and libertine dazzle of Italian Renaissance painting, which had just begun to attract American scholars and investors.

For the rest of his life, from a seat of fame and scholarship near Florence, Italy, Berenson, Class of 1887, enjoyed a love affair with his alma mater. Proof of that love remains today in Villa I Tatti, his elegant Tuscan mansion. Shortly after his death in 1959 the villa became Harvard’s scholarly foothold in Italy, and since 1961 it has been the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

During the estate’s heyday, beginning in 1901, it was a favorite destination for a constellation of friends who naturally gathered around the man who would soon be known as the most influential art historian of the 20th century. In the early days, members of the Bloomsbury set stopped by, and so did Edith Wharton and Gertrude Stein. Later came Harry Truman, Martha Gelhorn, J. Paul Getty, Hugh Trevor-Roper, Jackie Kennedy (who corresponded with Berenson up until his death), and Ray Bradbury, showing the scope of Berenson’s cultural reach.

Life at the villa during the Berenson years has recently been recaptured with the launch of a new oral history project that is accessible online.

“I took out my recorder and got going,” wrote Anna Bensted in an email. A former radio journalist and co-master of Eliot House with her husband, Lino Pertile, the center’s seventh director, she had arrived at the villa in 2010. Immediately, Bensted realized that voices from the villa’s past needed to be recorded. “Given that he died more than 50 years ago,” she said of Berenson and the fading echo of his influential world, “this was, to put it bluntly, urgent.”

Soundbytes: Villa I Tatti oral history

The result was Villa I Tatti: An Oral History. It features snippets of recorded remembrance 90 seconds long, some from servants and friends from the 1930s, which invite a listener to access the full interviews. Among those interviewed were Berenson’s last assistant, his valet, and the euphoniously named Fiorella Superbi, a onetime curator of his art collection.

Suberbi had been born on the estate during the 1930s and remembered singing the fascist songs she learned in primary school to Berenson’s wife, Mary. Superbi also recalled the villa’s occupation by the Germans during World War II, a time when Berenson, who had converted to Christianity in his junior year at Harvard, was barely tolerated by the Axis powers. He was a suspect and despised American, though an émigré beloved and protected by the locals.

William “Willy” Mostyn-Owen, a friend of Berenson in the 1950s who lived at the villa for two years, remembered meeting him, and recalled his habit of sizing up newcomers physically. “He’d look at you like you were a piece of sculpture,” said Mostyn-Owen during an interview. His presence in the oral history is a testament to Bensted’s drive to record people’s recollections quickly. Mostyn-Owen, who became director at Christie’s Auction House, died in 2011.

The site also includes oral reports of how the villa made the transition from home to research center. Michael Rinehart ’56, the center’s first librarian, recalled what it took to “transform this rather casual social environment (into) something more structured.” Before Harvard took over, he said, Berenson was the head of “a rather grand functioning household … like a little bit of Boston, 19th-century Boston, dropped into the middle of a Florentine villa.”

A look back

Bernard Berenson (second from right) at Harvard in 1887, the year of his graduation. Photos courtesy of Villa I Tatti

Berenson’s gift to Harvard headlines a June 25, 1933 story in The New York Times.

A Villa I Tatti interior in a photo by Alessandro Sardelli.

The villa’s lush gardens today retain a geometric splendor.

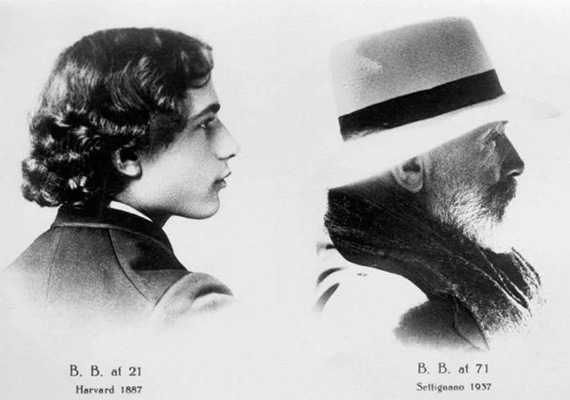

A diptych of graceful aging: Berenson at 21 and at 71.

The site has a picture-rich timeline reaching back to 1019, the year “Tatti” was first mentioned in a Latin document. “Visitors … always want to know more about the villa before Berenson,” said Bensted, who credited Italian designer Sabina D’Anna with the timeline’s look.

Vintage photos and Steve Ziger watercolors of a sweet pastel lightness help the site cast the spell of a villa that represented the heart of 20th century art history. The design is to “both evoke the past and also give a sense of the beauty of the place,” said Bensted, who praised the Web design of villa librarian Scott Palmer, “a fan of oral history and a digital whiz.”

Drawing on her journalistic experience with the BBC, National Public Radio, and WBUR, Bensted conducted interviews from 2010 to 2012 “to find out just what a typical day was like at I Tatti” during the Berenson era. She wondered: “What was it like to be one of those … lucky enough to receive an invitation to tea to meet Berenson? What was it like to work in the villa and see these guests coming and going?”

She posed questions regarding “Berenson’s concern for his reputation,” especially “his relationship with the art dealer Joseph Duveen, [which] led to divided opinion about his legacy in the world of at history.” (Duveen, the most famous art dealer of the early 20th century, had a high-risk, big-money career that was tinged with controversy.)

Berenson’s bequest to Harvard was made in 1933, and was reported in the New York Times. The idea was “to give future scholars … a transforming intellectual experience” of the kind Berenson had enjoyed at Harvard from 1884 to 1887, said Bensted. Berenson had studied with Charles Eliot Norton, Harvard’s first professor of fine arts; Barrett Wendell, whose “English 12” required daily themes (and set off in Berenson a love of good writing); and William James, whose early theories of psychology likely influenced Berenson’s belief that looking at art should be both emotional and systematic. (The Villa I Tatti site includes a section on Bernard and Mary as students at Harvard, where both arrived in 1884, he to the College and she to the Harvard Annex, a predecessor of Radcliffe College.)

But for nearly 30 years following the bequest, while Berenson was still alive, Bensted said “he had to work hard to convince Harvard that this was indeed a good idea.” The University had accepted the preemptive gift, but only predicated on getting an endowment for upkeep along with it, a requirement that “became a constant concern for Berenson,” she said.

That concern about money had a deep history. Berenson was an undergraduate at a time when “in general, Harvard presumed that its students were white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, male, and not too terribly worried about making a living,” wrote scholar Rachel Cohen. Berenson allayed his fears of being an outsider by befriending the likes of fellow outsider George Santayana. But he also spent most of his undergraduate tenure living with his parents near the rail yards of Boston’s North End, where his mother sold meals for extra money. The Harvard of 1884 did not have a single Jewish professor and numbered its Jewish graduates over the previous 220 years at about a dozen.

In all, wrote Cohen, Harvard was for Berenson “an anxious pinnacle of achievement,” yet one whose intellectual joys he wanted to see replicated in his beloved Villa I Tatti.

The man he became in Italy over almost 60 years — patrician, charming, influential, rich, complicatedly sexual — is now on display through the voices of those who knew him.