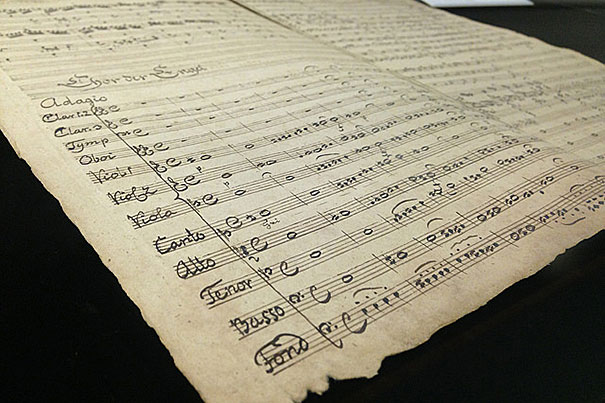

Joint exhibitions at Houghton Library and Loeb Music Library mark the 300th anniversary of composer C.P.E. Bach’s birth. In addition to his musical scores (photo 1, of “Heilig”), a wealth of material is now available, including several songs published by Bach in the annual Musenalmanach, a pocket-sized book containing mostly poetry but some music on folding plates (photo 2) and “Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen” (“An Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments”) from 1797 (photo 3). The treatise introduced techniques, like using one’s thumbs, still in use today.

Photos by Beth Giudicessi

Bach to Bach

Joint library exhibit showcases trove of work by composer C.P.E., son of Johann

Mozart said of Bach: “He is the father, we are the kids. Those of us who know anything at all learned it from him.”

Mozart referred not to the prolific and influential composer who typically comes to mind at the mention of the name, but to Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, the second son of Johann Sebastian. C.P.E. Bach’s legacy is the subject of joint exhibits at Houghton Library and Eda Kuhn Loeb Music Library that mark the 300th anniversary of his birth and the first publication of his complete works. The exhibits are open to the public and run through April 5.

“The focus of the Houghton exhibit is placing C.P.E. Bach in the literary, musical, and geographical context of the 18th century,” said Sarah Adams, Richard F. French Librarian of Loeb Music Library and keeper of the Isham Memorial Library, Harvard’s collection of rare music manuscripts. “Because of the role we’ve played in working with the new edition, it was appropriate to have an exhibit at the music library that brings C.P.E. Bach into the 21st century and educates people about the importance of the music he produced.”

C.P.E. Bach was an active composer, performer, and conductor from the 1730s to the 1780s. In addition to his musical scores, items on display include autograph fragments, portraits from his own extensive collection, handwritten edits to his father’s chorales, and a pocket calendar from the time when C.P.E. was music director for Hamburg’s five principal Lutheran churches.

“He was really known as an original genius in his lifetime, and there were contemporary French, German, and English writers who put C.P.E. Bach on a pedestal,” said Paul Corneilson, managing editor at the Packard Humanities Institute and guest curator of the C.P.E. Bach exhibitions, noting that C.P.E. helped bring Johann Bach’s work to prominence by contributing to his father’s 1802 biography. “I’m not suggesting that C.P.E. Bach should be on the pedestal and not his father, but I think his music should be better known and appreciated today. He really bridges the generation between Handel and J.S. Bach with his younger contemporaries: Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven.”

C.P.E. Bach published many of his own works, but was known to revise and recycle them — and works by others — using different instrumentation or parody texts. Determining what C.P.E. borrowed was one of the editorial challenges facing researchers as they prepared “C.P.E. Bach: The Complete Works.”

The new publication, a critical edition, attempts to provide an authoritative collection closely resembling the composer’s original intentions. Scholars relied on close cooperation among the Packard Humanities Institute, Harvard University, the Bach-Archiv Leipzig in Germany, and libraries around the world to obtain and compare original scores and copies that show C.P.E.’s changes.

Adams edited a volume of symphonies for the series. During her work, she discovered that one of their earliest printed editions omitted a measure, a mistake that was repeated in modern versions.

“It is a dramatic example,” she said, “but it’s an illustration of why it’s good to go back to the original sources.”

Corneilson said ongoing exploration for the complete works led to finding an early C.P.E. Bach cantata and a better understanding of the arias, duets, and choruses that he completed during his years in Hamburg. The new edition will include a never-before-published critical edition of his foundational keyboard treatise. It also will incorporate a large collection of formerly lost and unpublished manuscripts thought to be destroyed in World War II but found in 1999 by Christoph Wolff, the Adams University Research Professor and curator of the Isham Memorial Library, and Patricia Kennedy Grimsted, an associate of the Ukrainian Research Institute.

Harvard’s support of the project catalyzed the acquisition, cataloging, and opening of thousands of C.P.E. Bach sources.

“We deepened our collection in an area where there was already an existing strength,” said Adams. “We now have an extremely rich set of resources on hand for future research to be done.” At least two professors have arranged for their classes to visit the exhibits this spring to work with the Bach materials and other 18th-century holdings.

“It’s a terrific opportunity to be able to teach from primary sources,” said Adams. “There are multiple editions for several items on display — both the critical edition that has been produced, as well as 18th-century editions and 19th-century editions.”

As Harvard students compare notes, those melodies will come to life at a variety of C.P.E. Bach concerts over the next few months.

“We’ve provided parts and scores for a lot of performers,” said Corneilson. “So that’s very gratifying to know people are using the edition, and this music is going to be heard.”