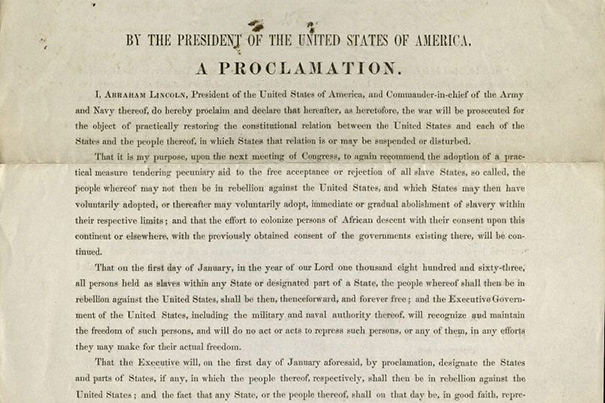

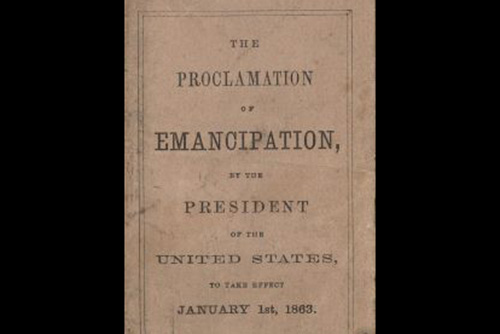

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued on Jan. 1, 1863.

Images courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University

The Emancipation Proclamation now

Harvard scholars ponder ongoing ripples of the document

In 1841, a young and depressed Abraham Lincoln confided to a friend that he would just as soon die except he had yet to accomplish anything to make people “remember he had lived.” Two decades later, the man who became the nation’s 16th president kept the country from fracturing in the Civil War and helped to end slavery with his historic Emancipation Proclamation. The document, issued on Jan. 1, 1863, declared, “All persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

Staff Writer Colleen Walsh of the Harvard Gazette asked scholars from across Harvard to reflect on the proclamation’s 150th anniversary, and how the document resonates today. Here are their thoughtful responses.

Freedom and military service

Drew Faust is the president of Harvard University and Lincoln Professor of History in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), and a scholar on the Civil War period.

Attention to the Emancipation Proclamation rarely focuses on a portion of the document that I have thought about often in recent years. Not only does the proclamation offer a promise of freedom to the slaves, Lincoln also includes a sentence very near the conclusion providing that “such persons … will be received into the armed services of the United States.” Freedom is in this revolutionary document linked integrally with the right of military service. African-Americans of the Civil War era understood that link very clearly and eagerly embraced the affirmation of their personhood and their place in national life that the opportunity to fight for freedom represented. Southern defenders of slavery likewise understood the threat it posed to the very foundations of their system. As Confederate Horace Cobb observed, “If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”

The link between military service and full citizenship and inclusion is one that has had powerful resonance in our own time. The end of “Don’t ask, Don’t Tell” and the full participation of gays and lesbians in our armed forces represent, as Lincoln described the Emancipation Proclamation itself, a profound “act of justice,” a carrying forward in our time of the ideals that he and his words inspired.

Among the vast holdings at Houghton Library is a signed copy of the Emancipation Proclamation once owned by Charles Sumner, Abraham Lincoln’s confidante and Secretary of State during the Civil War. Read more.

Civil rights, and freeing themselves

Annette Gordon-Reed is the Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Charles Warren Professor of American Legal History at Harvard Law School, and professor of history in FAS.

I’m not sure what resonance the Emancipation Proclamation has for the generations who came of age after the Civil Rights movement. I wrote a book with Vernon Jordan about his youth and early career, and he talks about going to “Emancipation Proclamation Day” ceremonies every Jan. 1 when he was growing up in Atlanta. It was a big deal, linking the end of slavery to the drive for civil rights in the 20th century.

Actually, it was not totally ignored. I grew up in Texas, and we celebrated Juneteenth, which commemorates the date that Union troops were finally able to take control of the state and enforce the proclamation. That Texas holiday has now moved beyond, across the country. The ritual of remembering the document that brought black men into the battle to fight for their freedom and for the Union and encouraged thousands of enslaved people to flee the plantations — freeing themselves — should always be a vital part of the story of black Americans’ journey through American history.

The political present, and personal reflections

Howard Gardner is John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

By no means an expert on the Emancipation Proclamation, your question prompted three thoughts:

1. In 1863, virtually no one could have conceived of a two-term president who is black.

2. [Southern author William] Faulkner is right: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” If we look at the current House of Representatives, or the controversy over guns, parts of the country are still fighting the Civil War.

3. As German Jews seeking to escape the Nazis, my parents were fortunate enough to make it to the United States, arriving on Kristallnacht, 75 years after the proclamation. For them, America was the country of Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt. And these two presidents remain my heroes as well.

A long way to go

Jonathan L. Walton is Plummer Professor of Christian Morals in FAS, professor of religion and society at Harvard Divinity School, and Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church.

The Emancipation Proclamation was the result of a multiracial, concerted effort of men and women who bore witness to the truth about slavery. Abolitionists like Angelina and Sarah Grimke, Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Sojourner Truth held a coherent moral framework that condemned the sin of slavery while affirming the equality of humanity.

Unfortunately, Abraham Lincoln, though full of political courage, lacked the moral animating impulse of these abolitionists. The politically expedient themes of black emigration undercut a vision of a multiracial democracy. And while Lincoln’s perspective was evolving at the time of his death, full citizenship for the formerly enslaved and their descendants remained an elusive dream.

Thus the Emancipation Proclamation, despite its significance, lacked the moral foci of its abolitionist forebears. Slavery so polluted the air of this nation with the noxious gases of race, gender, and class hierarchies that we continue to ingest its harmful social toxins 150 years later. Only a sincere and sustained moral defense of the equality of all people can help to purify our nation and provide this wonderful document with the ethical imperative of which its name signifies. This document is a powerful statement, but by no means the last word on the quest for human freedom.

Art and the proclamation

Diane Paulus is the artistic director of the American Repertory Theater and professor of the practice of theater in FAS.

The Emancipation Proclamation is a symbol of this country’s commitment to freedom and, while it was was penned by Lincoln 150 years ago, it still inspires us today. As part of our multiyear initiative around the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, the A.R.T. is facilitating a writing immersion program in the summer of 2013 that will challenge a group of local high schoolers to respond creatively to the Emancipation Proclamation.

The Proclamation Project will prompt students to make connections between the Emancipation Proclamation and the Civil Rights movement over the ensuing 100 years, the concepts of slavery and freedom, and the nature of civil war in today’s society (as it pertains to our families, our city, and our world). This project will culminate in a unique performance piece drawn from the words and writings of our teen ensemble. The Proclamation Project will enable us as a theater to explore this moment of history, and to investigate what it means for us today.