The rise, ruin of China trader

Baker Library exhibit, website track early U.S. firm’s business efforts, mirroring the times

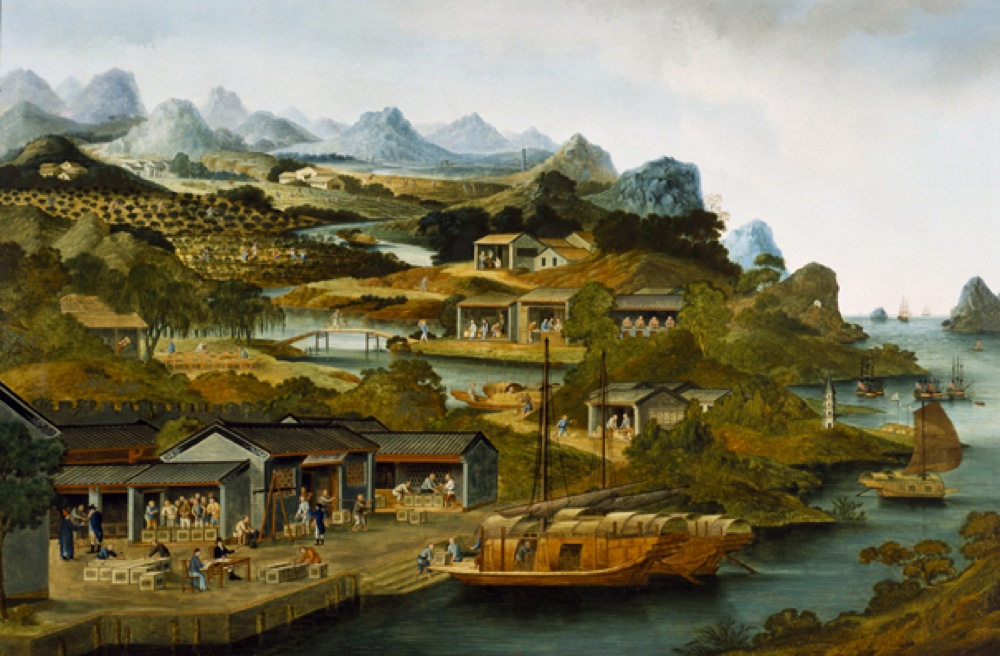

America’s insatiable desire for goods such as electronics and inexpensive clothing fuels much of its trade with China. But more than 150 years ago, when industrious U.S. merchants began to develop their own trading firms in the Far East, goods such as tea and porcelain predominated.

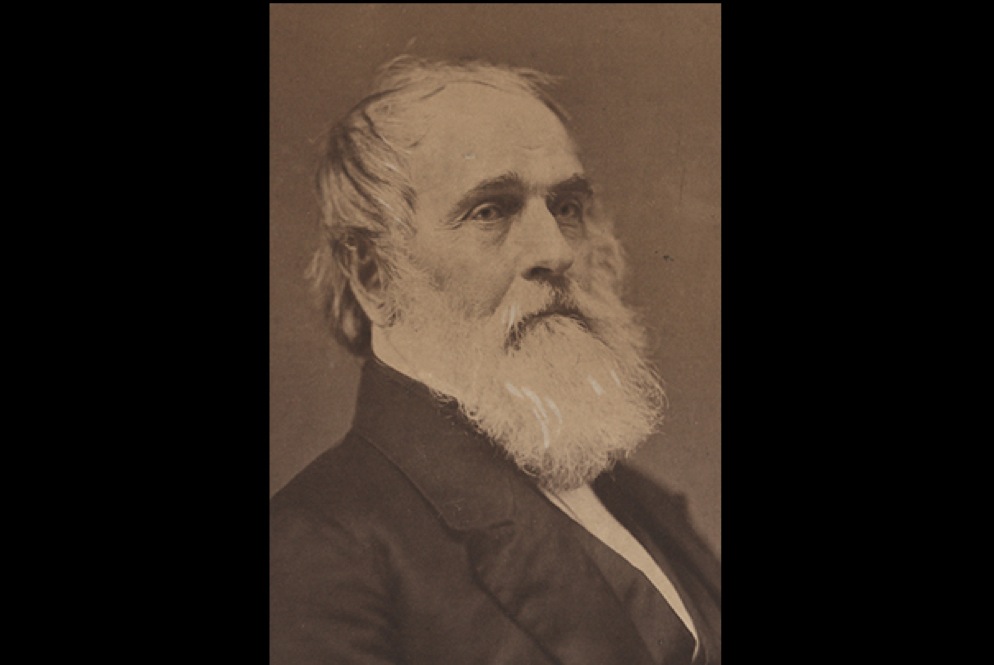

A research collection at Harvard Business School’s Baker Library offers visitors an in-depth look at the earliest days of the China trade, thanks in large part to a New England pioneer in the field and his company’s meticulous record keeping.

“It’s staggering. The company saved everything,” said Melissa Banta, the curator who helped to comb through the Baker Library’s Historical Collections archive on Augustine Heard & Co., one of the most respected and powerful U.S. trading houses in China in the mid-19th century. That research developed the exhibition and accompanying website titled “A Chronicle of the China Trade: The Records of Augustine Heard & Co., 1840-1877.”

The show is only open until next week, but its online counterpart will live on at the library’s historical collections website.

To create the show and the interactive online research guide, Banta drew from 800 volumes, 272 boxes, and 103 other containers in the Heard collection. Thanks to the family’s remarkable attention to detail, both professional and personal, the show and guide capture the day-to-day workings of the lively, lucrative, and ever-evolving merchant exchange. They also paint a rich picture of the key events and technological developments of the day, and evoke the emotional toll of living and working far from home.

Though he never married, the company founder Augustine Heard had four industrious nephews who joined the successful business. Their correspondence to family in America and their detailed memoirs offer an intimate look at their lives abroad. A page from the diary of Heard’s nephew Albert, who moved to China to join the firm just after graduation from Yale University in 1855, describes his rapid transformation.

“Then a boy with anxious and aspiring hopes now as it were a man,” he wrote, “doing a man’s part and a serious and sober part, responsible too, then looking forward to unknown duties & strange scenes, now those duties are familiar. … Then not even a clerk now a merchant & a head man of a firm. Truly I am changed.”

In something of a strangely fortuitous twist, Augustine Heard created his company during the First Opium War, the three-year conflict between China and the United Kingdom fought in large part over the British desire to import opium from India. China lost the war, and its ability to regulate the influx of opium, and Augustine Heard & Co. quickly capitalized on the open market. Material in the collection carefully documents the company’s involvement in the legal drug trade.

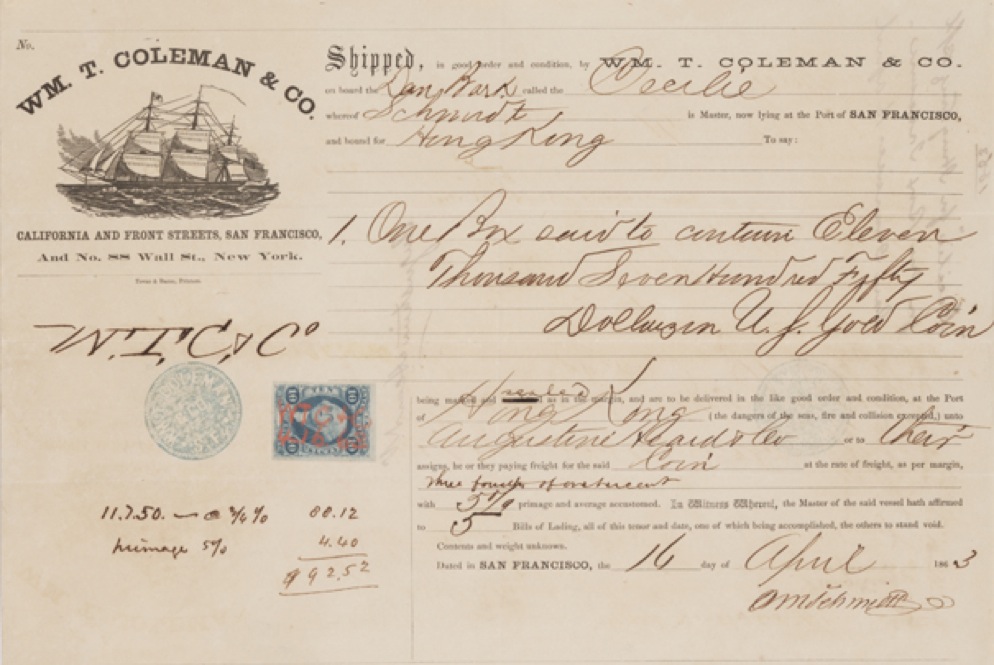

Included in the exhibit and website is information on the evolution of transportation. Clipper ships, sleeker sailing vessels with narrow hulls and larger sails, became the preferred means of moving merchandise across the seas, and Heard & Co. was quick to transform its fleet. Bills of sale and invoices that detail Heard’s investments in the newer, faster ships are part of the collection.

Heard & Co. eventually became one of the first companies to use steamships in the China trade. “It was an incredible revolution at the time. Not only were they opening up the ports, they were also trading in the interior,” said Banta, citing carefully drawn plans for a steamship included in a Heard logbook.

But while those advances proved profitable for the company, another new technology was its undoing. Enter the telegraph.

“You could do trading so much faster. You could get a better handle on fluctuation in prices. You could secure credit faster,” said Banta. “But things like this signaled the beginning of the end for Heard & Co. because it meant that smaller Chinese traders could now compete in the trade.”

In addition to telegrams generated by the company, items in the show and website track the firm’s decline, including its official bankruptcy papers from 1876. But thanks to the Baker Library, the story lives on in vivid detail.

“Certainly one of the legacies Augustine Heard & Co. left behind was this vast, impeccable record itself, which provides a professional as well as highly personal perspective into the China trade,” Banta said. “It was a pivotal moment when Westerners and Chinese were beginning to form diplomatic relationships, and China was entering into the mainstream of world trade.”

A collecting strength for Baker Library is the extensive records of American firms involved with 19th century China. The collections offer rich perspectives into early Sino-American relations, as well as insights into the complexities of the business lives of American traders in the treaty ports.

Viewers can access a comprehensive guide to the Heard family records or contact Baker Library Historical Collections at histcollref@hbs.edu for further information.

Share this article