Taking Charge with cellphones

Student taps smartphones, solar power to protect Amazon basin

Jeffrey Mansfield was aboard the riverboat Juan Felipe last August as it eased down the Arapiuns River, a branch of the Amazon a mile wide. In the distance was the lush green rim of the Brazilian rain forest. Despite the remote locale, Mansfield took out his iPhone and in moments was posting real-time pictures on Facebook.

Mansfield, a master’s degree student in architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, was taking advantage of a fact that is little known in North America: Remote corners of the vast Amazon River basin are increasingly covered by 3G networks. (3G is short for the third-generation networks widely used for cellphones, the Internet, video links, and other wireless communications.)

“One of the biggest surprises was how accessible the Internet was,” said Mansfield. “I never felt I was in a romanticized wilderness, completely separate from the world.”

Brazil itself has one of the highest densities of cellphone use in the world, and by 2014 even its most remote riverine forest regions will have reliable 3G coverage of the kind Mansfield enjoyed on the Arapiuns. A year ago, Vivo, Brazil’s largest wireless provider, distributed 200 Samsung smartphones to residents of the Tapajós-Arapiuns Extractive Reserve, an ecologically sensitive region inhabited by the mixed-race caboclo people.

These farmers, fishermen, and artisans of Ameridian descent live under thick jungle cover, managing beehives, and clearing little plots to grow maize, onions, cassava, and tree fruits. (Sustainable farming in these conditions is called agroforestry.) But these Amazon forest residents are also under pressure from large-scale soybean operations that clear swaths of endangered forest.

Power in the region is scarce and expensive, often parceled out in 15-minute increments from portable diesel generators. In some locations, there are solar-powered telecenters that use fixed solar panels. But that’s not enough in the power-short Amazon.

In August, Mansfield was in Brazil with the Portable Light Project, a nonprofit research, design, and engineering initiative developed by Boston-based Kennedy Violich Architecture Ltd. (Add in the Brazilian partners, and the project is called the Luz Portatil Brasil initiative.) At the heart of the project is a lightweight, flexible solar fabric that comes with a rechargeable battery pack and a USB port. A user can sling a solar fabric bag over the shoulder, go about the day, and return home at night with enough juice to power cellphones, lights, and other USB-powered devices.

The solar textile, with its flexible photovoltaics and solid-state lighting, can also be made into traditional-patterned dresses, hats, tarps, and household curtains.

During the 10-day sojourn, Mansfield and the others in his group conferred with Coopa Roca, a women’s sewing cooperative in Rio de Janeiro that reworked the solar fabric. The group also set up a base of operations in Santarem, a former rubber plantation boomtown blanketed by a haze from burning trash. Mansfield and the rest navigated hundreds of miles of the Tapajos and Arapiuns rivers to conduct solar-fabric workshops in 10 riverine villages. Quite happily, the visitors slept in hammocks, watched forest parrots at play, and ate a lot of fish, cassava, and native corn.

Mansfield, a first-time visitor, was awakened to both the charms of the remote Amazon and the ecological threats to it — and to what sensitive stewards of the lands its jungle residents are. He said cheap solar power and widening 3G networks provide a “double confluence” of factors that could help to protect rain forest ecology, improve the lives of residents, and empower them politically. “So many times, outsiders speak for people there,” said Mansfield. “They had to trust foreigners to speak for them, and it wasn’t always accurate. The portable light kit and cellphone allows them a voice.”

Mansfield, who is hearing-impaired, felt a kinship with the Amazon residents, since they can rely on others to talk for them. (Interpreter Jolanta Galloway, a freelancer who often works for Harvard, was present during Mansfield’s interview.)

The Amazon trip inspired Mansfield to suggest a “user guide” that enables residents to employ smartphones as digital multi-tools. (“The smartphone in my generation,” said Mansfield, “is like the Swiss Army knife.”) Forest residents could use technology to improve farming, health, banking, trade, and health practices. They have the cellphones — but they lack a tool kit and training for life-changing applications. He called that “the missing link.”

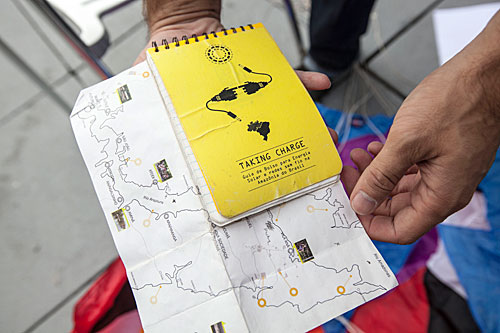

Back at Harvard this fall, Mansfield launched Taking Charge, a Kickstarter-funded project that will donate cellphones — loaded with helpful apps, along with a user guide printed on waterproof paper — to the region. Available in PDF form too, the guide would contain content from Amazon residents, including tips on beekeeping, husbandry, irrigation, and trade, along with foldout maps on the location of fuel stops, solar stations, and other infrastructure.

Accurate maps are at the heart of the Taking Charge tool kit. On a balcony at Gund Hall, Mansfield unfurled a kite that can be used to loft a cellphone 500 feet or more into the air. The phone’s camera, set on continuous shoot and held in a cut-off soda bottle with rubber bands, can snap high-resolution photos impossible to get from a higher-altitude plane. “You get phenomenal resolution,” he said. “It’s low-tech, high-impact.” (Google just recently started to use kites and hot air balloons as mapping platforms.)

At his Gund Hall workstation, where Mansfield also writes a Taking Charge blog, he showed a prototype of the users’ guide. It will contain kite-mapping instructions, a biodiversity guide, and profiles of regional entrepreneurs, who are experts in beekeeping, fishing, organic farming, weaving, and food processing.

This winter, during a second Portable Light Project trip to the Amazon, Mansfield will gather more local content and conduct workshops on kite mapping and mobile-phone applications. He reached his Kickstarter goal, and will distribute 15 copies of the user guide — more if he has the funding. The target is for at least one copy in each of 10 villages, which may have as few as 20 families and as many as 100.

A scheme like this can be scaled up, said Mansfield. He sees the 2,500-square-mile Tapajós-Arapiuns region as a pilot locale for the whole Amazon, which is dotted with villages whose residents yearn to connect with one another.

Mansfield sees a future in which cellphones help Amazon residents scour the Internet for new farming methods of sustainable agroforestry, advice on do-it-yourself engineering projects (like tractor repair), and tips from regional entrepreneurs. They should be able to document their livelihoods, their lands, and any threats to either. They will be able to gather weather information — important in an ecosystem where sealike rivers can rise by 60 feet. And Amazon forest residents may be able to study distant markets, jumping past middlemen to get the best prices for their goods. Smartphones can also be a way for people to tell their stories, to one another and to the world.

“That’s our goal,” said Mansfield of the multifaceted smartphones, “to make them part of every day life.”