While parts of the U.S. economy have recovered from the recession, American jobs haven’t returned with them. Unemployment remains above 9 percent nationally for the third straight year. Harvard experts offer insights into what such static joblessness means for the nation, and what policymakers and others can do to fix a balky system.

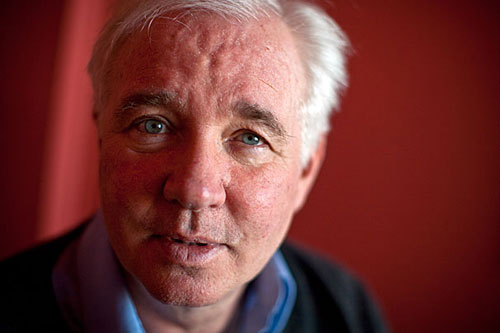

Photo illustration by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Jobs wanted

Harvard analysts suggest Rx for America’s unemployment doldrums

December offers a built-in reprieve from the harsh economic buffeting of recent years. Stores slash prices, customers shop, and boom-time cheer returns. This holiday season, however, many Americans are still hoping for the basic gift of a job. For the third straight year, the nation is likely to ring in New Year’s Day with an unemployment rate above 9 percent.

A succession of federal bailouts — of large banks, financial services companies, and the auto industry — has shown that, in dire cases, the government will act as a bank of last resort. But for many American workers, an employer of last resort is hard to find.

“What if we thought of people as too big to fail?” asked Alexander Keyssar, Matthew W. Stirling Jr. Professor of History and Social Policy at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS).

It’s a provocative question, and one that professors, researchers, and others at Harvard are working to address. But fixing America’s long job slump will require more than just government intervention, they say. Getting people back to work also will take creative solutions from business, nonprofit, and higher education leaders.

And Harvard analysts say that fixing the more insidious causes of lingering unemployment — everything from rising inequality to inadequate education to dwindling blue-collar jobs — will require attention beyond the 2012 election cycle, where the topic has become a dominant campaign issue.

Their innovative suggestions include guaranteeing the unemployed access to job-training programs; pushing business and academic initiatives to foster competitiveness and bypass political stalemate; planting deep geographic and educational roots in communities to spur creativity and stability; and jump-starting the huge but languishing housing market.

Counting the uncounted

The history of formally counting the unemployed began in Harvard’s home state in the 1870s. But the way that employment was then measured bears little resemblance to the monthly figures trumpeted in headlines now, said Keyssar, author of “Out of Work: The First Century of Unemployment in Massachusetts.”

The first surveys relied on federal and state census data to gauge the percentage of people unemployed at any point in the previous year. Between 1880 and 1930, about 20 to 35 percent of Americans were jobless for some period each year, according to Keyssar — a number that sounds catastrophically high to the modern ear. Even before the Great Depression, routine periods of unemployment were a fairly normal part of blue-collar workers’ lives.

“Those early numbers were actually more useful if you wanted to understand the impact of unemployment on a society or a labor force,” he suggested.

Because of the recent recession, the number of Americans who have been unemployed at some point in the past year is again near 20 percent, he estimated. One unsettling likely reality is that blue-collar workers may never again enjoy the job security and prosperity they had in the mid-20th century, when unions were strong and industry giants like American automakers reigned supreme.

But with the help of innovative policies, Keyssar believes, workers can bounce back into jobs more quickly.

Policies tying layoffs to guaranteed entry to job training programs would help less-skilled workers to transition, he said. (Of course, traditional education helps, too. The unemployment rate for workers with college degrees is half that of their non-degree-holding counterparts.) Stronger union protections would help to reverse the trend of declining benefits and job security in working-class occupations in service and manufacturing, he added.

The federal government should prioritize funding for unemployment benefits, which are worth much less in most states than they were decades ago, Keyssar said.

Talking to the job creators

Some American jobs are indeed lost for good. But a key to replacing them lies in understanding where the American economy is most competitive and where it can become more so. With that in mind, Harvard Business School (HBS) Dean Nitin Nohria recently kicked off the U.S. Competitiveness Project, a yearlong initiative designed to take the pulse of America’s business leaders.

The goal isn’t just to study the issue, but to mobilize the business community, policymakers, and academics to promote the cause of competitiveness.

“Much of the public discourse is about what the government should do,” said Jan Rivkin, Bruce V. Rauner Professor of Business Administration at HBS, who is running the project with Michael Porter, Bishop William Lawrence University Professor. But as Congress and the president remain gridlocked on providing major economic fixes heading into the 2012 elections, Harvard’s business experts are taking their case directly to the community they study.

“We’re asking business leaders to reflect on what their roles and responsibilities are” for stimulating the economy and creating jobs, Rivkin said. “There’s also a role for the academy to generate new ideas for public debate.”

“The bad news is that answers are unlikely to come from Washington in the short term,” Rivkin added. “The good news is, they don’t have to.”

In October, HBS sent a survey to its alumni to gauge their thoughts on America’s competitiveness and how to improve it; more than 10,000 responded, according to Rivkin. The project is now examining preliminary data from the survey, which it will make available to researchers around HBS and Harvard.

But thinking about competitiveness means more than just figuring out how to attract and grow companies. The hard part, Rivkin said, is doing that while maintaining wages and living standards for American workers.

Invest in places, as well as people

While it’s difficult to estimate the number of American jobs that have been offshored in recent years, a 2009 analysis by Rivkin and his students found that between 21 and 42 percent of U.S. work could be performed abroad. Nonetheless, Rivkin’s research has shed light on the importance and the benefits of investing in American workers.

“There’s been a tendency to underestimate the hidden costs of offshoring,” he said. In addition, U.S. companies often “underestimate the benefits of staying in one place and putting down roots.”

One example he cites often is Corning Inc., the scientific and industrial products manufacturer, and its eponymous hometown, Corning, N.Y. The city of 11,000 near the Pennsylvania border is now “one of the best places to make breakthrough products in the world,” Rivkin said, thanks to the company’s investment in the local school system, community colleges, and town infrastructure.

“Corning operates in something like 60 countries around the world, but it has managed to turn a small town into a hotbed of innovation,” Rivkin said. “If you just move from city to city to whatever town gives you the lowest labor cost, you’ll never develop that.”

American business should look to emulate such fruitful examples, said Joseph Bower, HBS’s Baker Foundation Professor and co-author (along with Harvard faculty Lynn Paine and Herman Leonard) of the new book “Capitalism at Risk: Rethinking the Role of Business.”

Bower and his co-authors visited business leaders in Asia, Latin America, Europe, and the United States and found that, across the globe, companies worried about similar problems, including maintaining jobs and a healthy consumer economy as living standards rise. (An estimated 800 million people worldwide will join the ranks of the middle class by the year 2030.)

“In emerging nations, there are hundreds of millions of people who are in effect outside the system, and in some places companies have actually been very good at devising ways at getting people into the system,” Bower said.

U.S. companies could adopt those strategies at home, he added, by investing in solutions that target education deficits, environmental damage, and rising health care costs in the communities where they operate.

“You have to step up,” Bower said. “We’re not talking about corporate social responsibility here. We’re talking about companies devising ways of doing sustainable business.”

Housing still counts

One area that government could help to jump start, however, is the lagging housing market. At its pre-recession height, new home building accounted for roughly 17 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), according to Nicolas Retsinas, a senior lecturer at HBS, a lecturer at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), and director emeritus of the Joint Center for Housing Studies. Housing now accounts for only 13 percent of GDP.

“For the past 50 years, we’ve been spoiled; housing has been considered the bedrock of society,” Retsinas said. “It’s still foundational, but now that foundation has cracks.”

Of the 800,000 foreclosed properties now on the market, only 300,000 are owned by the government, according to Retsinas. If the government agreed to sell more foreclosed homes to developers in bulk, the homes could be converted to rental properties — a good way to stimulate the remodeling and rental markets that have already shown a tendency to recover more quickly than the market for new homes.

Focus on the family

As the United States copes with long-term unemployment, analysts said it’s also important to ramp up social supports. Unstable finances can create unstable families, said Kathy Edin, a professor of public policy and management at HKS who studies marriage and family structure in low-income communities.

As blue-collar jobs vanish, white, working-class communities in particular have seen an increase in divorce rates, as have what Edin calls “fragile families” — cohabiting couples raising children outside of marriage, who face a higher probability of splitting up. Edin said that increasingly complex family structures can put financial pressures on families and on single parents, while creating emotional pressures on children, compounding the cycle of poverty.

“If you can’t give couples some foothold on economic stability, you’re just going to increase divorces,” Edin said. There is some evidence that “modest economic investments in couples’ economic lives can increase disadvantaged couples’ stability pretty dramatically,” Edin said.

Many low-income couples whom Edin has studied would rather raise their children in a two-parent family, she said, but are reluctant to marry if they’re not financially stable. “I think we can do a lot to help them do that — not by preaching, but by simply giving them the tools to stay together.”

A role for nonprofits

As the economic doldrums drag on for many, charitable donations and government supports sag. So nonprofit organizations — especially those helping the unemployed and the poor — are adjusting to “the new normal,” and in many cases have to do more with less.

“This isn’t a short-term crisis that [nonprofits have] to get used to,” said Jim Bildner, a senior research fellow at the Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations. “It is a more profound strategic challenge,” exacerbated as nonprofits and foundations find themselves filling gaps in the societal safety net that historically were filled by government. Housing, shelters, food pantries, and other critical services are increasingly displaced to the nonprofit sector, he said.

To meet these challenges effectively, he added, many nonprofits are narrowing their focus and focus on their core functions. But they also have a role to play in helping the jobless to get back on their feet.

“Where nonprofits can be particularly effective is in helping change the conditions that surround the unemployed [by offering] job training and other supportive services that make future employment opportunities more likely,” he said.

Traditional social service nonprofits aren’t the only organizations feeling the pinch to help the unemployed. Churches are stretched thin, too.

“Twenty years ago, people felt churches would be the kind of organizations that will pick up the slack when the safety net starts to have holes in it,” said Dudley Rose, lecturer and associate dean of ministry studies at Harvard Divinity School. “From the beginning we overestimated the resources that congregations have.”

Mainline Protestant churches have been declining in the United States for decades, Rose said. “The idea that churches are going to step in and pick up the social safety net is probably pie in the sky.”

What religious leaders can do, besides offering spiritual guidance and support, Rose said, is to organize the faithful around economic issues the way some groups have organized around social issues such as abortion in past decades.

“What we’ve seen in recent times is a much louder voice from the religious right,” he said. Churches that fall to the left may be ripe for a revival, Rose said.

Grassroots movements such as Occupy Wall Street and its local offshoots (including Occupy Harvard) have already attracted adherents who believe social and economic justice to be core tenets of their faiths’ good works. The Greater Boston Interfaith Organization, for example, has worked extensively with Occupy Boston.

“I think there’s a lot of room to claim moral high ground there and to become more active,” Rose said.

“The sky has not fallen”

Despite the dearth of jobs and the other persistent economic problems facing the nation, however, many Harvard experts still expressed optimism about the country’s long-term prospects.

“The economy retains enormous strength,” Rivkin said. “The sky has not fallen. There are pieces that are dangling.”